Keywords

antihypertensive agents, healthy lifestyle, hypertension, medication adherence

List of abbreviations

BP: blood pressure

CKD: chronic kidney disease

HMOD: hypertension-mediated organ damage

HTN: hypertension

Take-home messages

- Resistant hypertension represents a difficult to control hypertension despite adequate drug therapy.

- Ruling out Pseudo-Resistance and investigating causes of resistance (behavioural- pharmacological factors, or “secondary” HTN) is crucial.

- Resistant hypertension should be managed at specialized centres with the expertise and resources to exclude pseudo-resistant hypertension.

- Management of resistant hypertension involves encouraging a healthy lifestyle, enhancing patient adherence and modifying/adding new classes of antihypertensive medications.

- Untreated resistant hypertension increases the risk for major cardiovascular events.

Definition

Resistant hypertension is defined as the body’s inability to control high blood pressure (BP), to office values less than 140 mmHg systolic and/or less than 90 mmHg diastolic, despite treatment with at least 3 classes of drugs, including a diuretic, with maximal (or maximally tolerated) doses. Inadequate control of BP should be confirmed by ambulatory or home blood pressure measurements following the patient’s undertaking of appropriate lifestyle changes and whose adherence to therapy has been confirmed [1].

Pseudo-resistant hypertension occurs when uncontrolled hypertension is inaccurately diagnosed and/or managed. A false diagnosis can be caused by incorrect measurement of blood pressure (with an overestimation of BP measurements), white coat HTN (high office but normal out-of-office measurements), or marked brachial artery stiffness (stiff arteries that do not yield with inflation causing an overestimation of systolic BP). Improper management may be either patient-related (poor adherence to treatment) or physician-related (therapeutic inertia e.g. improper combinations or inadequate doses of antihypertensive medications) [2].

Causes of resistant HTN

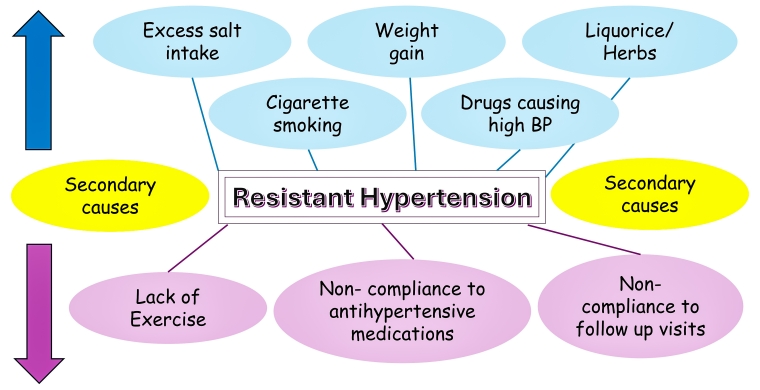

Determining the possible causes of resistant hypertension represents a major step in patient management and many factors can be implicated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Causes of resistant hypertension.

- The inability to maintain a healthy lifestyle: which includes failure to reduce bodyweight or perform regular exercise, excessive alcohol consumption, or non-compliance to salt restriction, prescribed drug doses or follow-up visits.

- The effects of certain chemical substances which may elevate BP or antagonise the hypotensive effects of medications through different mechanisms, causing difficulty in controlling high BP. These mechanisms include:

- Salt and water retention: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. ibuprofen, indomethacin), medicinal and anabolic steroids, oral contraceptive drugs containing oestrogens, antiangiogenic cancer therapy (vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors), sodium-containing medications (e.g. effervescent), and liquorice.

- Noradrenergic stimulation: drugs used for weight reduction (e.g. sibutramine), illicit drugs (e.g. cocaine, amphetamines), nasal decongestants (e.g. phenylephrine), antiangiogenic cancer therapy (vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors), antidepressant drugs (e.g. monoamine oxidase inhibitors) and some herbs (e.g. ephedra).

- Imbalance of vasoactive substances resulting in high endothelin and low nitric oxide levels: immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., cyclosporine A).

- Secondary causes of HTN

HTN due to secondary causes are often difficult to control and treatment should mainly focus on the underlying condition (Table 1).

Secondary causes of HTN include:

-

- Renal parenchymal disease which may impair the effectiveness of treatment [3]. When the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, an adequate dose of a loop diuretic should be included in the treatment of uncontrolled BP before considering a diagnosis of resistant HTN [1].

- Renovascular disease: renal artery stenosis due to atherosclerosis or fibromuscular dysplasia.

- Endocrine disorders: suprarenal gland disorders (primary aldosteronism, Cushing syndrome, pheochromocytoma), thyroid gland disorders (either hyper-or hypothyroidism), and hyperparathyroidism.

- Obstructive sleep apnoea.

- Aortic coarctation.

Table 1. Diagnosis and management of secondary causes of HTN.

BiPAP: bilevel positive airway pressure; BP: blood pressure; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; CT: computed tomography; HTN: hypertension; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PET: positron emission tomography; TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone.

Prevalence and phenotype

Resistant HTN is not uncommon, as it affects about 10-20% of treated hypertensive patients [1]. The prevalence reaches up to 30% if pseudo-resistant HTN is included.

Resistant HTN is more common in males, older adults (≥75 years), patients of African descent, patients with diabetes mellitus, and patients with hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD; e.g. chronic kidney disease [CKD], heart failure, left ventricular hypertrophy and atherosclerotic disease). Obese hypertensive patients and patients with high dietary salt intake are also more prone to develop resistant HTN [2]. Finally, it has been suggested to consider resistant HTN as a “salt-retaining state" secondary to inappropriate aldosterone secretion, with an increased vascular volume [4].

Diagnosis

Because of the many factors that may predispose a patient to or cause resistant HTN, a thorough clinical assessment should be undertaken.

The patient’s interview should focus on possible characteristic features of secondary causes of HTN, their compliance to regular exercise, salt restriction and prescribed medications, and any possible additional drug intake.

Proper measurement of BP is an essential part of the clinical examination before diagnosing resistant HTN. Following the proper standardised techniques in office BP measurement can differentiate patients with pseudo- from patients with true resistant HTN. Using an accredited, well-calibrated and properly maintained BP measuring device is recommended. Out-of-office BP measurement helps to confirm the diagnosis of true resistant HTN [5]. A thorough general examination is needed to search for any signs of an endocrine disorder. A twelve-lead electrocardiogram may indicate left ventricular hypertrophy or hypokalaemia (which suggests primary aldosteronism).

Laboratory investigations should include conventional tests (e.g. renal function, serum potassium levels, albumin/creatinine ratio) and any additional diagnostic tests for endocrine diseases if a secondary cause is suspected (Table 1).

Transthoracic echocardiography can diagnose the presence of aortic coarctation, and it can detect left ventricular hypertrophy.

Additional investigations (e.g. abdominal computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] for adrenal gland tumours, CT/MRI aortography for aortic coarctation) may be needed, based on clinical suspicion (Table 1).

HMOD needs to be investigated and detected at an early stage as resistant HTN increases the risk of developing an HMOD that leads to cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (e.g., heart failure, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias), cerebrovascular diseases (e.g., ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, transient ischaemic attacks), renal diseases (e.g., hypertensive nephrocalcinosis and renal impairment), or vascular diseases (e.g., increased carotid and peripheral vascular stiffness).

Globally, considering the high level of expertise necessary to carry out these assessments, patients should be managed at specialised centres offering enough experience and resources.

Treatment

Lifestyle modifications

The value of adherence to a healthy lifestyle in reducing HTN has been demonstrated in many studies [6]. Physician recommendations should include improving salt restriction, encouraging exercise, recommending weight reduction and cessation of smoking, and avoiding ‘on-shelf’ or over-the-counter drugs.

Pharmacological treatment

Spironolactone (25-50 mg OD) should be proposed in addition to antihypertension medications (Class IIa, Level B), especially in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Spironolactone is not suitable in patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 nor in patients with serum potassium levels >4.5 mmol/L. Caution should be taken when adding spironolactone to drugs blocking the renin angiotensin system, as the combination may lead to serious hyperkalaemia. Frequent kidney function and serum potassium levels should be evaluated soon after initiation of spironolactone and frequently thereafter. If spironolactone is not effective or is not tolerated, it can be replaced by eplerenone.

The addition of a beta-blocker (if not already indicated) should also be considered.

In chronic kidney disease patients, hydrochlorothiazide might be replaced by a long-acting thiazide-like diuretic (e.g., chlorthalidone) to overcome excess salt and water retention that accompany renal impairment.

Lastly, a centrally acting drug, an alpha-blocker, hydralazine, or a potassium-sparing diuretic should next be considered.

Improve patients’ drug adherence

Reducing the number of antihypertensive pills can improve patients’ adherence to medications. It is recommended to give patients with resistant HTN a single pill combination of suitable antihypertensive medications to improve their adherence to treatment, reduce the drug side effects and improve efficacy and speed of action of drugs [5, 7].

Using the latest technologies such as new smart phone apps can also help patients to adhere to their medications through setting reminders for drug intake [8].

Promising new antihypertensive drugs

Finerenone is a non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist that is currently being tested as an alternative to spironolactone in cases with troublesome side effects [9].

Angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) is not yet approved for treatment of HTN, although it has demonstrated better BP reduction than some antihypertensive medications like valsartan and amlodipine [5].

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) caused 10 mmHg reduction of elevated systolic BP in patients with diabetes mellitus and CKD [10]. Yet, SGLT2i are not yet indicated for treatment of HTN per se.

Other experimental drugs include baxdrustat and lorundrostat (which selectively inhibit aldosterone synthase enzymes), neuropilin-1 (NRP-1) agonists (reduce vascular tone; preclinical animal studies only), and zilebesiran (reduces circulating angiotensin II; phase 1 trials) [10].

Device therapy

Renal vascular denervation is gaining popularity in the treatment of resistant HTN. Many studies showed the effectiveness of catheter-based ablation of renal afferent and efferent sympathetic nerves in controlling HTN, for up to 3 years [11, 12]. Yet, this procedure cannot be performed in patients with moderate-severe renal impairment (<40 mL/min/1.73 m2) or in patients with secondary HTN. The BP-lowering effect of the procedure is only modest (6 mmHg reduction of office BP measurement), and it is cost ineffective. These many concerns, in addition to the lack of long-term safety evidence, led the procedure to gain a Class IIb recommendation in the 2024 European Society of Cardiology hypertension guidelines [1]. A rare complication of the procedure is renal artery stenosis, which was reported in 0.25%-0.5% of patients [13]. Many other neuro-modulator devices are under study, but because of the insufficient, conflicting evidence, no recommendations have been made for the use of these devices in hypertensive patients.

Prognosis

Patients with resistant HTN are generally at a higher risk for cardiovascular events when compared to patients with well-controlled HTN; this is partly because cardiovascular risk increases with increasing BP levels, and partly because HTN is usually associated with other cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease [2]. Uncontrolled HTN increases the risk of target organ damage including myocardial infarction, stroke, end-stage renal disease and cardiovascular death by about six to eight times [14].

Patient-oriented message

If you are a hypertensive patient, visit your physician regularly to ensure proper control of your blood pressure. If your hypertension is difficult to control, consult your treating physician as s/he may modify or add new drugs to your medication list. Adopt a healthy lifestyle that includes limited salt intake, lower weight, more exercise and no cigarettes.

Impact on practice

Impact on physicians: failure to achieve target BP in hypertensive patients causes frustration in physicians and a lack of trust in pharmacological treatment.

Impact on patients and healthcare system: resistant HTN predisposes patients to cardiovascular complications with higher morbidity and mortality. In addition, it puts a high financial burden on the patients and the healthcare systems as more drugs are needed to control HTN and more office visits are required to evaluate the success of treatment [15].

Conclusion

Resistant hypertension is not rare in treated hypertensive patients, but its prevalence declines with the accuracy in the screening for pseudo-resistant HTN. The work-up of patients presumed to have resistant hypertension is complex and should be managed at specialised centres. The intensification of antihypertension drugs, especially adding spironolactone, should be proposed. Catheter-based renal denervation may be considered in selected patients, after a shared risk-benefit multidisciplinary discussion.