Background

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) complicated with arrhythmia is an emerging distinct entity, known as “arrhythmic MVP”(1). The clinical phenotype as well as the burden of arrhythmia are highly variable, with both atrial and ventricular arrhythmia being described as part of the arrhythmic MVP. Furthermore, a certain subset of patients with MVP were found to be at a higher risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) due to ventricular arrhythmia (VA), independent of the degree of mitral regurgitation (MR) and left ventricular systolic function (2, 3). However, the relationship between MVP, VA and SCD is not entirely understood. Several features, such as impaired ventricular mechanics due to abnormal tethering forces, myocardial fibrosis, and association of mitral annular disjunction (MAD), might be helpful in identifying patients at risk (1, 3) Certain genes are associated with MVP, such as FILAMIN A (FLNA) and DACHSOSUS1 (DCHS1)(1). In clinical practice, routine genetic testing is not justified and is limited to patients with syndromic diseases (Marfan and Loeys Dietz syndrome)(1). The description of a number of pathogenic (P) or likely-pathogenic (LP) variants associated with cardiomyopathies and/or channelopathies in patients with MVP raises the question if this overlap contributes to the development of arrhythmic events and SCD (4, 5).

Patient presentation

We present the case of a 40-year-old female patient who experienced sudden cardiac arrest at 36 y.o. due to ventricular fibrillation (VF). Her ECG showed flattened T waves in the lateral leads, while bi-leaflet MVP and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were documented at the transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). She received an ICD in secondary prevention. The ICD was interrogated 6 months after, revealing numerous monomorphic non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT), despite treatment with amiodarone. She was referred to an electrophysiology (EP) study. VT was induced after stimulation of the basal lateral left ventricular wall, 1 cm under the mitral annulus. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) was successfully performed. The patient was referred to our center for second opinion, reporting no cardiac symptoms.

Is it mitral valve prolapse or Titin cardiomyopathy that led to sudden cardiac arrest

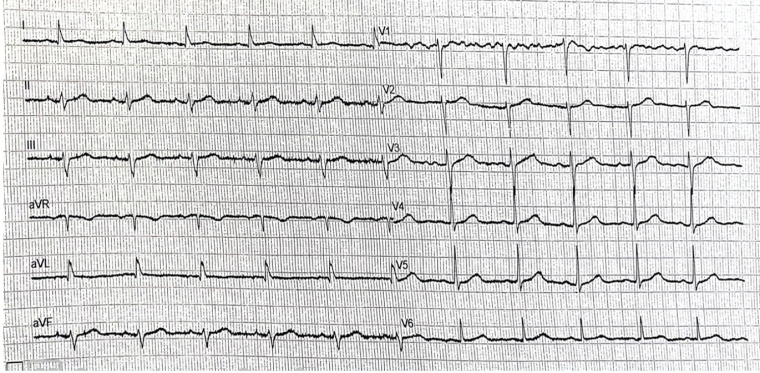

ECG showed sinus rhythm, with a slurred S wave in inferior leads and slurred R wave in lateral leads, as well as flattened T waves in aVL, with corrected QT of 460ms. No significant ventricular arrhythmic events were noted at the current ICD interrogation.

TTE was performed. The LV had a normal size, however, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was mildly impaired (48%) with mild longitudinal dysfunction (GLS -16,6%). The mitral valve appeared thickened and redundant, with bi-leaflet prolapse and mild regurgitation. MAD was seen, with a length of 4-5mm measured in mid-systole.

Tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) of the lateral wall revealed a second systolic peak, with a velocity of 17cm/s. Through speckle-tracking analysis, a double peak strain pattern is seen on the basal infero-lateral wall (orange arrows).

The patient’s family history was highly suspicious for an inherited cardiac disease, as her father died suddenly at 66 y.o. Furthermore, a paternal cousin required permanent pacing for a high-degree AV block at 25 y.o. and died suddenly at 30 y.o, while another paternal cousin had an aborted cardiac arrest at 21 y.o. Genetic testing was performed after genetic counselling, revealing a truncating (tv) likely-pathogenic (LP) Titin variant (TTN c.85150C>T. p.(Arg28384*) in a heterozygous form.

Cascade genetic testing was then proposed to the sister and surviving cousin.