Definitions

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is characterised by the displacement of one or both mitral valve leaflets during systole, where they move upwards by at least 2 mm above the level of the mitral annulus in the sagittal view (1). There are two main underlying causes of MVP: myxomatous MVP, which is distinguished by an excess of tissue, thickening and/or elongation of the chordae, as well as potential annular dilation and calcification; and fibroelastic deficiency, which is the most common form and is characterised by thinning and elongation of the chordae, with a higher risk of rupture (1).

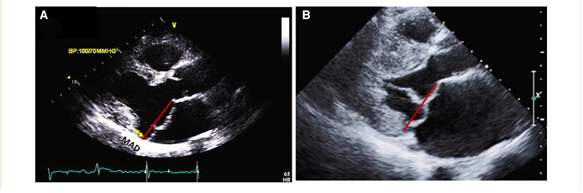

Furthermore, MVP can be associated with mitral annulus disjunction (MAD), which involves the separation between the ventricular myocardium and the mitral annulus during systole, particularly occurring beneath the posterior leaflet scallops but primarily at the central posterior one. MAD is associated with the loss of normal mechanical annular function due to its detachment from the ventricular myocardium while maintaining its electrical function, thereby isolating the left atrium and ventricle electrically. Although it is typically observed in conjunction with MVP, it can occur independently (2).

The arrhythmic mitral valve complex (AVMP) is defined by the presence of MVP (with or without MAD), combined with frequent and/or complex ventricular arrhythmias (VA) in the absence of any other well-defined arrhythmic substrate. There are two main phenotypes of the AVMP: the severe degenerative mitral regurgitation (MR) and the severe myxomatous MVP independent of MR severity (1,2,3).

Assessment

Cardiovascular imaging plays a crucial role in identifying and characterising the existence of MVP, MAD and the phenotypes of AVMP. Echocardiography and CMR are the most powerful diagnostic techniques not only for the diagnosis but also for stratifying the arrhythmic risk (1).

With echocardiography

The evaluation of MV morphology initiates with two-dimensional (2D) transthoracic Doppler echocardiography (TTE). MVP can be immediately identified and distinguished between myxomatous MVP and fibroelastic deficiency phenotypes (4,5,6).

In the parasternal long-axis view, during mid-diastole, measurements of leaflets’ length and thickness should be conducted. The leaflets' redundancy can be evaluated using M-mode over the mitral valve in the parasternal short-axis view (4,5,6).

The presence of MAD should be detected as well. It may manifest at various locations on the mitral annulus, but it carries an increased risk of VAs when observed at the posterior LV wall. Occasionally, MAD is associated with a distinct mid-systolic to late-systolic spike on the lateral mitral annulus, as detected by Doppler. To measure MAD's length, the parasternal long-axis view at end-systole is employed, defining it as the distance between the mitral annulus and the systolic bulge of the ventricular myocardium (typically ranging from 5–10 mm in long-axis view) (5,6).

Subsequently, a comprehensive evaluation of MR severity should be carried out following the current guidelines. Quantifying MR involves various quantitative methods, the most commonly utilized one is the flow convergence technique (proximal isovelocity surface area-PISA), which relies on shifting the color baseline to define the radius of the flow convergence. These methods measure variables such as regurgitant volume and effective regurgitant orifice area. The established thresholds for severe degenerative MR are a regurgitant volume of ≥60 mL/beat and an effective regurgitant orifice area of ≥40 mm2. However, it's noteworthy that the mortality risk starts increasing even at values between 20–30 mm2, with a linear rise as values become larger (5,6).

In terms of LV, some MVP patients exhibit disproportionate LV enlargement due to the volume load associated with the prolapsing volume, which is the space between the mitral annulus and the prolapsing mitral leaflets in end-systole (5,6).

Furthermore, mechanical dispersion, based on longitudinal strain in the apical 4C view, has shown potential in predicting the risk of VAs in MVP patients. However, more research is needed due to limited data (1,5,6).

If uncertainties persist, alternative imaging techniques such as transesophageal echocardiography (TOE), CMR, and stress echocardiography can be employed. Quantitative exercise echocardiography, in particular, can help identify valvular lesions that may have been underestimated during initial imaging (5,6,7).

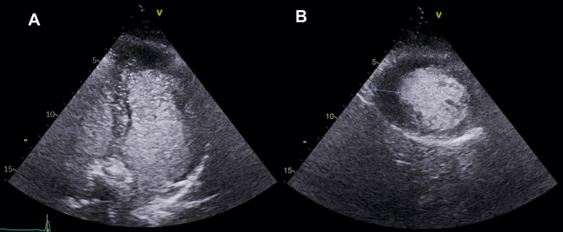

CMR serves as a pivotal tool in improving the stratification of arrhythmic risk and filling in the gaps in data that may be missing in echocardiography. (8).

Balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) cine sequences can thoroughly examine cardiac morphology and function, detecting LV remodelling signs.

As for echocardiography, it is imperative to document key mitral valve characteristics, including bileaflet MVP and myxomatous MVP. The assessment should encompass measurements of the mitral annulus at both end-systole and end-diastole in both anteroposterior and inter-commissural aspects. Additionally, factors such as leaflet diastolic thickness, leaflet length, prolapsed distance, and the presence or absence of systolic curling, if applicable, should be mentioned, and quantification is necessary (8).

A comprehensive evaluation of MAD around the mitral annulus involves acquiring six left ventricular long-axis cine sequences with a 30° interslice rotation. Assessing MAD severity typically requires measuring its longitudinal length, at least from the long-axis view, and possibly its circumferential extent expressed in degrees (8,9,10).

Moreover, CMR enables the calculation of MR volume and fraction thanks to phase-contrast velocity mapping sequences (5,6).

Lastly, CMR's unique capability lies in its ability to reveal information about the presence of myocardial fibrosis thanks to late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images. In cases of MVP, fibrosis is frequently located near the annulus, primarily in the basal left ventricular wall, including the papillary muscles and inferior wall. Notably, only LGE within the mitral apparatus (papillary muscles and peri-annular region) shows a clear pathophysiological association with arrhythmias, while the significance of LGE in other regions remains uncertain in this context. T1 mapping sequences can also identify diffuse fibrosis in the LV, and this has been linked to an increased risk of complex ventricular arrhythmias (10,11,12,13).

In summary, performing CMR gives pivotal information, but it requires expertise and should be conducted in specialised centres due to its advanced nature.

How to classify the mitral valve prolapse-speaking genetics

The mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is traditionally classified into syndromic and non-syndromic, and the latter is further distinguished into familial or sporadic.

With regards to the syndromic MVP, dysregulation of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) cytokine family pathogenic variants in the TGF-β receptors genes type I (TGFBR1) and II (TGFBR2) are involved. TGFBR 1- more than FBN1- in Loeys-Dietz, FBN1 alongside TGFBR genes in Marfan, elastin (ELN) disease-causing variants in Williams-Beuren, COL genes in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, are the most commonly described and well proven associated genes in this category. In addition, the syndromic type also involves some aneuploidy syndromes, mainly trisomies 18, 13, 15

Whist there is a widely-recognized genetic background in patients with syndromic MVP, MVP represents a non-syndromic finding in most cases. Although sporadic cases are acknowledged, parental MVP is associated with higher prevalence of decedents MVP in the community. Only a small subset of individuals with the MVP phenotype present with ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD). The incidence of the so called arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse (AMVP) or malignant MVP, is estimated at up to 0.4% per year depending also on the severity of mitral valve prolapse, associated symptoms and ejection fraction. (14,15)

How mitral valve prolapse is inherited- suggested genes and chromosome loci

There are reports on X-linked inheritance, with FILAMIN A (FLNA) disease-causing variants affecting the mitral valve apparatus, with more severe phenotype in men and progressive disease involving also other valves starting in early childhood. FLNA is a widely expressed hub protein involved in cardiac development, particularly in leaflets during fetal valve morphogenesis.(16) Other X-linked genes associated with systemic conditions such as the DMD gene (involved in Duchenne-muscular dystrophy), as well as genes involved in other dystrophinopathies with milder-in some cases-clinical expression, are also correlated with MVP.

In the majority of cases with a familial distribution, a Mendelian inheritance of an autosomal dominant pattern with variable expression and disease penetrance is reported.

An example of autosomal dominant inheritance involves the DACHSOUS1 gene (DCHS1) that encodes a member of the cadherin proteins family (MMVP2 locus in chromosome 11). Variants causing loss of function reduce the protein stability through their contribution in planar cell polarity.(17,18)

Genetic variants such as DAZ Interacting Zinc Finger Protein 1(DZIP1) which are involved in primary cilia expression were found to have an impact on the MVP development. This role of primary cilia function defect on MVP genesis is highlighted similarly in individuals with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, where changes in PKD1 and PKD2 genes- also play a role in primary cilia formation- coexist with MVP in a significant percentage. This latter is an example of a systemic condition where mitral valve prolapse is observed.

Of note, variants in DCHS1 and DZ1P1 have been captured in both familial and sporadic forms of the condition.

Other familial forms have been associated with matrix Metalloproteinase genes, LMCD1 (encoding for LIM and cysteine domain transcription factor regulator of cell migration and replication). GLIS encoding for GLI-related Kruppel-link zinc finger protein, a transcriptor regulator and TNS1 (Tensin 1) involved in focal adhesion control. All the aforementioned genes participate in mitral valve evolution and, consequently, the relevant pathogenic variants are associated with degeneration of mitral valve and prolapse pathology.(18,19)

Loci on chromosomes 16 and 13 have been identified and “blamed” for MVP are commonly inherited in a mendelian autosomal dominant pattern.(20,21)

A hypothesis of interplay between gene-related substrate and genetic related trigger for arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse

In an effort to investigate further the correlations between arrhythmia and MVP phenotype within the population, case studies have provided intriguing prospective insights.

A truncating variant has been identified in FILAMIN C gene (FLNC), an actin-binding protein that is critical for the structural integrity of the sarcomere in cardiac and skeletal muscles, has been found to be associated with an arrhythmia phenotype of mitral valve disease.(22) The FLNC gene, although closely related with the aforementioned gene encoding Filamin A, does not seem to cause degeneration and dysplasia in the mitral-valvuloventricular complex, and, therefore, the mechanism proposed is its contribution as an arrhythmogenic substrate via the gene impact on the “bonds” between the cells, which is subsequently triggered or “activated” by the structural mitral valve abnormality and the associated mechanical forces.

Along the same lines of “double-hit” hypothesis requiring the co-existence of a gene-related substrate and a gene-related trigger, a case report described a patient with variants of unknown significance in both the LMNA (encoding an intermediate filament responsible for maintaining nuclear shape in cells, and regulating transcription and translation) and the SCN5A (encoding for the sodium channel alpha–subunit 5), raises the possibility of a coordinated and synergistic action of the two genes.(23) A similar mind-set applied in a familial LMNA frameshift change producing a truncating variant. This particular modification was associated with a phenotype of DCM, arrhythmia and MVP with MAD. The phenotype was well segregated in the family.

The theory of genetic susceptibility for arrhythmia in MVP patients was studied in a cohort of unexplained young deaths, which genetic evaluation of three individuals with autopsy- determined lone MVP revealed pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants (as per ACGM classification) in the DMD-encoded dystrophin, RYR2-encoded ryanodine receptor 2 cardiac calcium release channel, and TTN-encoded titin. However, the study had limitations.(24) An identical concept applied on the identification of CACNB2 gene alternations resulted in loss of function of the protein encoding a subunit that plays an important role in the expression and function of calcium channels, in a 48 year-old male with “malignant phenotype” of MVP.(25)

Gene alterations correlated with loss of function in HCN4( hyperpolarisation-activated cyclic nucleotide channel 4) are related with MVP alongside atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, sinus node disease and variable degree of conduction blocks with an increased trabeculation phenotype.(26,27)

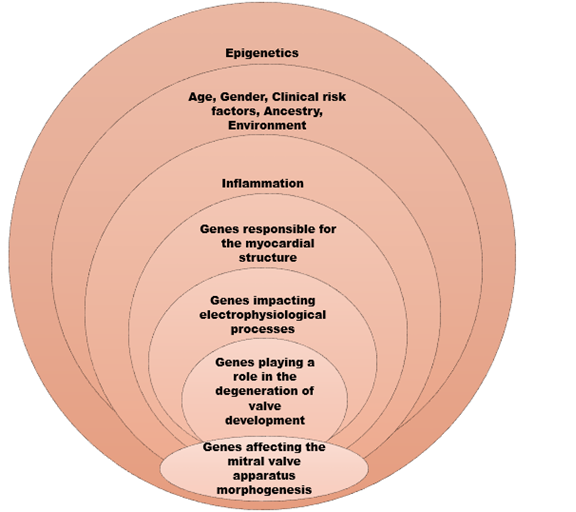

A recent metanalysis, extracted three cardiomyopathy related genes, namely ALPK3, BAG3, and RBM20 implying the potential interdependence between MVP and cardiomyopathies.(28) This was the largest metanalysis of GWAS to date located in total 16 genetic loci, responsible for the AMVP phenotype, by combining the knowledge from contemporary genotyping algorithms with transcriptional and proteomic analysis from mitral valve tissue.

Taking this further, Roselli et al, created a polygenic risk score for prediction of MVP risk, involving the age, gender, clinical risk factors (ie hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, myocardial infarct) and ancestry components, which is a promising attempt for future screening, management and potential therapeutic targets.

How to select candidates for genetic testing or screening

Systematic routine genetic testing in the mitral valve prolapse population is not currently recommended and there is no specific gene panel offered currently to probands and their relatives, except for the cases on which the finding appears part of a syndrome or a systemic condition, signs which can be extrapolated by the physical examination and appropriate diagnostic tests. Clinical screening of the first degree relatives of individuals with MVP of arrhythmic features has been proposed.

To ascertain if the genetic alterations outlined previously are merely over-representation or have evolved by chance, more research is required.

Due to the paucity of genetic data in MVP, the clinical value of genetic counseling is still restricted Nevertheless, in case of “arrythmogenic” presentation, positive familial history, features suggestive of an overlap with cardiomyopathy or with syndromic aortic disorders genetic counseling should be offered and careful evaluation of the use of genetic test performed.

Moreover, the role of environmental factors and epigenetics in arrhythmic mitral valve phenotype are yet to be determined. Regulatory roles of RNA-binding proteins on splicing and variants in deep intronic sequences point towards enlightening directions in the era of rapidly evolving genomic technology.(29,30)

Extended linkage studies for mapping candidate regions, whole exome sequencing and trio analysis in families with arrhythmogenic mitral valve prolapse and genome-wide association studies interrogation are essential to illuminate the interactions among genetic substrates between MVP and SCD.

Taking into consideration the aforementioned data in our armamentarium, the image below depicts and summarises the genes and processes participating in AMVP genesis. (Figure 3)