Introduction

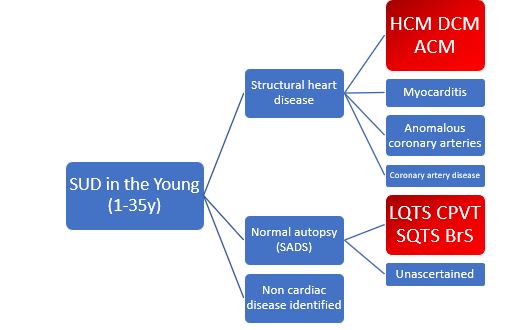

After sudden unexpected death (SUD) in the young, a significant number of individuals present an underlying cardiac disorder, which can be hereditary. These deaths can then be classified as cases of sudden cardiac death (SCD) when the autopsy identifies a cardiac or vascular anomaly as the probable cause of the event. Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of SCD in older persons, whereas in the young (1 to 35 years of age), SCD is more often caused by structural heart disease, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM), myocarditis, and congenital anomalous coronary arteries.

In a considerable number of cases of SCD among children and young adults, a cause of death is not found after a exhaustive autopsy examination including toxicologic and histologic studies. These deaths may be assumed to be sudden arrhythmic death (syndrome), or SAD(S). The most common causes are congenital long-QT syndrome (LQTS), Brugada syndrome (BrS), short-QT syndrome (SQTS), and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) (Figure 1).

On the other hand, a considerable number of cases present with a sudden cardiac arrest (SCA). In nearly 80% of individuals presenting with SCA, who are resuscitated, the cause is cardiac. Despite implementation of SCA protocols, it remains a significant factor leading to mortality worldwide.

The idea that SCD or SCA can occur in individuals who may not have a specific disease, even in athletes with regular screenings, highlights how challenging it is to identify the underlying cause. The aim of this article is to summarise in a practical guide how to address SCD or SCA individuals and their relatives.

General Considerations

- A multidisciplinary team with appropriate expertise should serve as the central element of a thorough investigation, since they maximize the chances of making a diagnosis for survivors of sudden SCA and victims of SCD. An enthusiastic team leader is essential to facilitate relationships between participants and minimise the impact of non-co-location.

- Families with an SCA or SCD and a suspected genetic cause need to be counselled and genetic testing conducted, to ascertain risks, benefits, and results, and the clinical implications of genetic testing.

- In parallel with the investigation process, family members of people who have been affected by SCD or SCA (and their families) should receive psychological care. Where appropriate, grief counselling and peer support should also be offered in addition to psychological assessment by certified professionals.

Example of participants in a multidisciplinary team

- Clinical leader - Secretarial support

- Lead coordinator - Database administration

- Regional coordinators/nurse specialists - Governance

- Adult and pediatric cardiologists - Pathologists

- Genetic counsellors - Clinical scientists

- Clinical geneticists - Psychologists/social workers

- Noncardiac specialists as needed

Table 1 Adapted from Stiles MK, Wilde AAM, Abrams DJ, et al. Heart Rhythm. 2021.

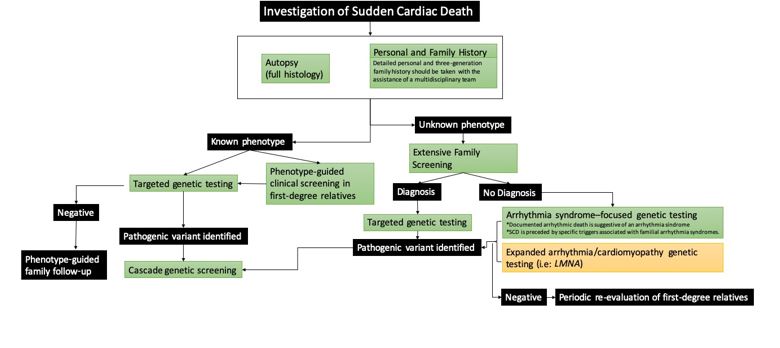

Investigation of Sudden Cardiac Death

As mentioned above, in subjects under 35 years of age, the most common causes of SCD are inherited cardiomyopathies and primary electric disorders. This genetic aetiology is increasingly complex, with great heterogeneity and sometimes incomplete penetrance. Several studies have investigated the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic protocols for the study of SCD aetiology, including conventional techniques, such as electrocardiogram (ECG), and more complex ones, such as genetic testing or pathology (Figure 2, black branch). Here, we describe a step by step approach:

Proband's personal and family history

Family history must be thoroughly investigated for major cardiac events, especially SCD at a young age; this is a red flag. Family trees should also be drawn for at least three generations.

On the proband, we will investigate previous sentinel symptoms (syncope, chest pain, palpitations), abuse of recreational drugs, prescribed medication and, if available, premorbid investigations (previous cardiac investigations and rhythm monitorisation around the time of death (i.e. loop recorder). The age, sex and circumstances of the event are of critical importance as they can provide important insights into the underlying cause (i.e. emotional or physical stress, swimming, acoustic triggers, seizure).

Autopsy

In addition to the proband's past medical and family history, postmortem expert analysis of the heart is crucial. Collecting at least 7-10 samples for histology is recommended, as it may reveal vital information (inflammation or an incipient cardiomyopathy). Ideally, two of the following three should be saved: a small piece of fresh frozen heart, a small piece of fresh frozen spleen/liver/ thymus, and EDTA blood. These are useful for toxicology, infection and DNA extraction for postmortem genetic testing.

Investigation of the family

When phenotype is unknown: A screening programme for the family after a SCD in a young person is very effective even when an autopsy is not performed or definitive. First-degree relatives should be thoroughly evaluated. As part of the evaluation, at least the following tests are performed: medical history, standard and high precordial lead ECG (to detect Brugada syndrome), echocardiography, exercise testing, and Holter monitoring. A CMR may be helpful in some cases.

When phenotype is known: the diagnosis of relatives at risk should be in line with current recommendations from expert consensus and guidelines.

Genetic testing

Firstly, families should be counselled about the expected benefits and potential outcomes of genetic investigations prior to testing. In cases where the deceased is the proband and a postmortem diagnosis is established, targeted genetic testing may be performed directly after autopsy or deferred until first-degree family members have been clinically evaluated. The identification of a pathogenic variant may facilitate genetic cascade testing in the family to identify at-risk individuals with no current clinical features or incipient abnormalities.

On the other hand, in an SCD case where the phenotype is unknown, arrhythmia syndrome–focused genetic testing of the proband should be considered if 1) documented arrhythmic death (such as torsades de pointes arrhythmias leading to ventricular fibrillation) is suggestive of an arrhythmia syndrome, and/or 2) SCD is preceded by specific typical triggers associated with familial arrhythmia syndromes. Furthermore, expanded genetic testing for cardiomyopathy genes (such as LMNA, FLNC) has been studied and can increase the diagnostic rate, although it should be recognized that the yield is lower.

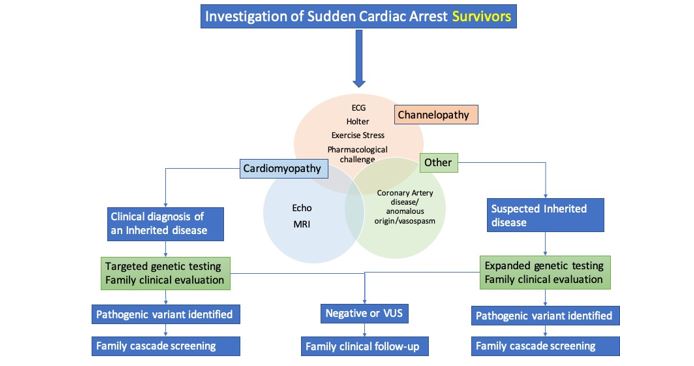

Investigation of Sudden Cardiac Arrest

Similarly to the evaluation of SCD, the diagnostic approach to survivors of SCA involves a variety of tests in an effort to exclude underlying structural heart disease, primary electrical diseases, drug or toxin exposure and acute reversible causes. Compared to SCD, here we have the advantage of having a surviving patient, which increases the chances of reaching an accurate diagnosis (Figure 3).

Family, personal history and physical examination

If the patient is awake, or family members are available, he or she should be asked about previous cardiac disease, medication intake, recreational drug abuse, previous symptoms (chest pain, palpitations, syncope), and the circumstances surrounding the cardiac arrest (sport, stressful situation, sounds), as well as witness information.

Along with a complete physical examination and personal history, it is crucial to collect information about family history of sudden death, especially at a young age. Ideally, we should obtain an three-generation pedigree.

Laboratory tests

Exclude electrolyte abnormalities and toxins.

Evaluation for structural heart disease

- Electrocardiograma (ECG): in addition to acute abnormalities, the ECG can reveal chronic conditions as acute coronary syndrome or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, respectively. It should be part of the immediate evaluation and repeated as necessary.

- Coronary imaging/provocative test: to exclude coronary artery disease, dissection, vasospasm or anomalies not considered fully at first presentation.

- Echocardiography: for evaluation of cardiac structure and function in all SCA survivors.

- Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR): for evaluation of acute or chronic myocardial disease when there is not a clear underlying cause.

Evaluation for primary electrical diseases

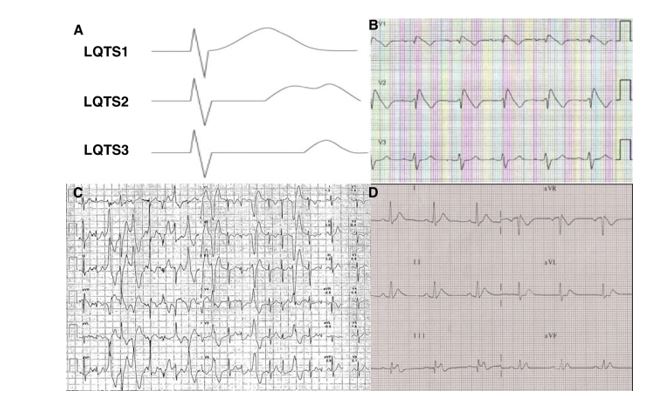

ECG: in channelopathies, an ECG is often diagnostic, although the abnormalities may be intermittent (Figure 4). It should be obtained a high precordial leads ECG, at resting and lying to standing (LQTS).

- Ambulatory monitoring: it may reveal intermittent or latent abnormalities (vasospasm, Brugada pattern, nonsustained arrhythmias).

- Exercise testing: it is important for the evaluation when the SCA occurred during physical activity. In patients with apparently normal hearts, exercise testing can reveal a LQTS and CPVT.

- Pharmacological challenge: some of the primary electrical disorders may still be present despite no evidence of abnormalities on any of the preceding tests. In selected patients we can perform procainamide or epinephrine challenges for Brugada syndrome and catecholaminergic syndromes, respectively.

Genetic Testing and evaluation of family members

In SCA, genetic testing is of paramount importance, since it can confirm a diagnosis with familial implications, but it can also guide substrate-specific treatment as well as establish a prognosis. Furthermore, genetic testing can identify patients during the concealed phase of a genetic disease such as arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy.

Therefore, genetic evaluation of SCA survivors, including only genes where there is robust gene–disease association, is recommended for those with a diagnosed or suspected genetic cardiac disease phenotype. It may be worth considering genetic tests that cover a wider range of conditions when it becomes apparent that a familial trait is likely.

For individuals with SCA in whom a diagnosis of a hereditary disease is reached, a family assessment should be performed before, during or after the genetic study. If a specific aetiological diagnosis already exists, the clinical work-up should be directed towards that pathology. If there is no diagnosed entity, a general cardiologic evaluation of first-degree relatives can yield the diagnosis of a heritable disease in a relevant number of families. There is not a clear established protocol but it should include: ECG, echocardiogram, Holter monitoring and, stress testing. In selected cases it may be expanded to pharmacological challenges and CMR.

Conclusion

Sudden cardiac death is a rare but tragic event. A inherited heart disease is a major cause of SCD in young adults, and it has significant consequences for the relatives. The diagnostic approach to SCD and SCA is complex and sometimes inconclusive. It is extremely important to perform a thorough and expert postmortem examination. This includes a comprehensive past medical history, a family pedigree, and an evaluation of the premorbid history. The experience of our group shows a high diagnostic yield by applying a systematic multidiscplinary protocol for these cases.