Abbreviations

CAV: cardiac allograft vasculopathy

CKD: chronic kidney disease

CVI: calcineurin inhibitors

CYP3A4: cytochrome P450 3A4

HDL: high-density lipoprotein

HTx: heart transplantation

ISHLT: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation

LDL: low-density lipoprotein

LDLR: low-density lipoprotein receptor

LPL: lipoprotein lipase cholesterol

PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

VLDL: very-low-density lipoprotein

Background

Dyslipidaemia is common in patients who have undergone heart transplantation (HTx) and predisposes them to the development of both atherosclerotic disease and cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV), leading to cardiovascular events [1,2]. Hypercholesterolaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, hyperhomocysteinaemia, hypertension, hyperglycaemia, obesity, and insulin resistance occur with a high frequency in transplanted patients. Lipid abnormalities are associated with endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in the general population. In addition, hypertriglyceridaemia has been identified as a predictor of CAV. Long-term follow-up studies have revealed that components of insulin resistance syndrome significantly predict subsequent development of CAV and cardiovascular complications [1,3,4].

Causes of dyslipidaemia after heart transplantation

The immunosuppressive therapy, including calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), given to patients can worsen pre-existing dyslipidaemia or result in the development of dyslipidaemia [1,2]. Steroids cause weight gain and exacerbate insulin resistance, leading to increases in total cholesterol, very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and triglycerides and in the size and density of LDL particles. CNI increase the activity of hepatic lipase, decrease lipoprotein lipase cholesterol (LPL) and bind low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLR), resulting in reduced clearance of atherogenic lipoproteins. A greater adverse impact on lipid profiles is seen with cyclosporine than with tacrolimus [2].

Hypercholesterolaemia, in a rabbit heterotopic cardiac transplant model, has been shown to be associated with CAV, and transplanted coronary arteries were more affected by hypercholesterolaemia than native coronary arteries. Hypercholesterolaemia promotes fibro-fatty proliferative changes to the intimal hyperplasia seen in most patients with CAV [1,5].

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy and atherosclerosis

CAV and atherosclerosis are atheromatous diseases, characterised by increased cell adhesion molecular expression leukocyte infiltration, similar ambient cytokine profiles, aberrant extracellular matrix accumulation, and the early and protracted build-up of extracellular and intracellular lipids. Intimal smooth muscle cell migration, endothelial dysfunction and abnormal apoptosis are observed in both diseases. Emerging evidence also indicates that stem cells may play a significant role in vascular repair and remodelling in both diseases. The pathogenesis of atheromatous diseases remains a challenge. The vascular disease of allografts is a useful model of atheromatous disease, from which knowledge about the native disease can be drawn, and vice versa. As average donor age has increased, the possibility of both conditions coexisting in donor and recipient has made discernment of processes more challenging [1].

Donor factors including sex, hypertension, diabetes, and tobacco use are independently associated with recipients’ CAV and atherosclerosis. Older donor age confers a greater risk of CAV development regardless of the age of the recipient. A heightened awareness for the development of CAV is warranted when using older donors in adult HTx, in particular with recipients 40 years of age or older [3].

CAV is an accelerated form of coronary artery disease in the transplanted heart and continues to limit the long-term survival of recipients [3,5,6]. Recent insights have underscored the fact that innate and adaptive immune responses are involved in the pathogenesis of CAV [3,5]. There are several recipient factors and traditional risk factors that can lead to a CAV development and progression - male sex, pre-transplant ischaemic heart disease, higher body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia and smoking [6]. Improved immunosuppressive drugs, including mycophenolate mofetil and proliferation signal inhibitors, as well as statins (in part via immunomodulation), have beneficial effects on CAV progression [3].

Three main strategies for CAV prevention are under investigation - inhibition of growth factors and cytokines, cell therapy, and tolerance induction. However, because individual responses to an allograft change over time, assays to monitor the recipient’s immune response and individualised methods for therapeutic immune modulation are clearly needed [3]. Alloantigen-independent factors include donor-transmitted coronary artery disease, surgical trauma, ischaemia-reperfusion injury, viral infections, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, and glucose intolerance [7]. Routine induction therapy with basiliximab was associated with reduced growth of the intima of the vessel during the first year after HTx [8].

Management and drug interactions

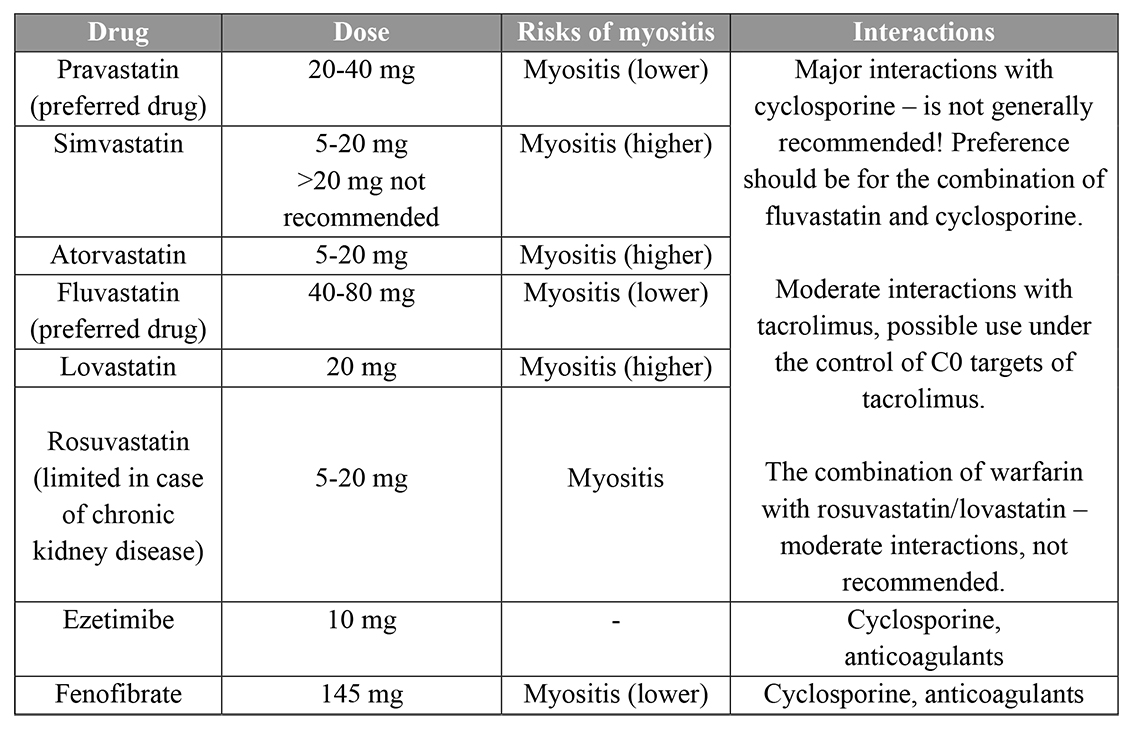

Statins have a similar effect on lipids in transplant recipients as that in the general population and can also improve outcomes in heart transplant recipients [2,9]. According to the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) guidelines, in adults, the use of statins beginning 1 to 2 weeks after HTx is recommended regardless of cholesterol levels [9]. Due to pharmacologic interactions with CNI and risk for toxicity, initial statin doses should be lower than those recommended for hyperlipidaemia [9]. Fluvastatin, pravastatin, pitavastatin and rosuvastatin have less potential for interaction [2,9]. Recommendations for doses of hyperlipidaemia medications in patients after HTx and drug interactions are presented in Table 1 [2,9,10].

Table 1. Recommendations for doses of hyperlipidaemia medications in heart transplant patients, risks and interactions.

Several potential drug interactions must also be considered, especially with cyclosporine, which is metabolised through cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) and may increase systemic statin exposure and the risk of myopathy. Cyclosporine increases the blood levels of all statins [2]. Tacrolimus is also metabolised by CYP3A4 but appears to have less potential for harmful interaction with statins than cyclosporine [2]. Care is required with the use of fibrates, as they can decrease cyclosporine levels and have the potential to cause myopathy. Extreme caution is required if fibrate therapy is planned in combination with a statin. Cholestyramine is not effective as monotherapy in heart transplant patients and has the potential to reduce absorption of immunosuppressants; this potential is minimised by separate administration [2].

Statins are recommended as the first-line agents for lipid lowering in transplant patients. Initiation should be at low doses with careful uptitration and caution regarding potential drug-drug interactions. For patients with dyslipidaemia who are unable to take statins, ezetimibe could be considered as an alternative in those with high LDL cholesterol, as well as the use of fibrates [2,10]. Cholestyramine is not effective as monotherapy in heart transplant patients and may reduce absorption of immunosuppressants [2].

Adverse effects

The most frequent adverse effects of statins consist in their influence on skeletal muscles and liver function. Statins may cause myopathy, myositis, or rhabdomyolysis, which may, in turn, result in acute kidney injury. Toxic liver disease may also develop, expressed by increased transaminase activity in serum. Other potential adverse effects include autoimmune conditions, arrhythmias, conduction disorders, as well as gastrointestinal and urinary tract dysfunctions. Susceptibility to the occurrence of adverse effects is highest among patients treated with large doses of statins, elderly patients, as well as individuals receiving medication metabolised by CYP3A4, which is also responsible for the metabolism of some statins [11]. In addition, creatinine kinase levels should be monitored in all children receiving statins [9].

Adverse effects resulting from drug interactions are more often encountered in the case of lipophilic statins (simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin) metabolised primarily by CYP3A4 than in the case of hydrophilic statins (fluvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin) using other metabolic pathways [11].

Future perspectives

Statins are a well-known and effective therapy but there are no outcome data available for ezetimibe, which should be reserved for second-line use. Future studies should also focus on second- and third-line therapies, as well as recommended doses of all drugs that can be recommended for dyslipidaemia management.

More evidence is needed for PCSK9 inhibitors in specific populations, including patients with severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) and on dialysis and after heart transplantation [2].

Apheresis treatment in patients after HTx is well tolerated. Besides its lipid-lowering effects, it also affects other systems (oxidized LDL particles, coagulation, C-reactive protein, adhesion molecules, plasma viscosity, monocytes, inflammatory HDL particles). These parameters may have a major impact on the deterioration of CAV [12]. Future studies should focus on when the apheresis can be prescribed - in the group at high risk of dyslipidaemia? In case of generalised atherosclerosis disease development?

Statins may prevent fatal rejection episodes, decrease terminal cancer risk, and reduce the incidence of coronary vasculopathy by their immunosuppression effect. Additional prospective studies are needed to investigate further and explain this association [13].

Conclusion

- Dyslipidaemia is a frequent complication after HTx for multiple reasons - from pre-transplant history and comorbidities to immunosuppression. Statins are the first-line therapy and should be used in all post-transplant recipients to prevent or to treat dyslipidaemia that can also lead to improvement in long-term outcomes.

- In addition, the transplant physician always needs to consider drug interactions and to check laboratory tests more frequently when administering new treatments.

- Dyslipidaemia is also one of the risk factors for CAV. Future studies should focus on how to prevent and to decrease the frequency of post-transplantation dyslipidaemia, which may impact positively on the incidence of atherosclerosis and CAV and improve long-term survival.

- Recipients receiving advanced age donor hearts should be monitored more closely to minimise the potential for CAV development.