Abbreviations

ALL acute lymphocytic leukaemia

APC antigen-presenting cell

CAR-T chimeric antigen receptor T-cell

CMR cardiac magnetic resonance

CRS cytokine release syndrome

EF ejection fraction

EMB endomyocardial biopsy

ESMO European Society of Medical Oncology

FDA Food and Drug Administration

GLS global longitudinal strain

ICIs immune checkpoint inhibitors

irAEs immune-related adverse events

LGE late gadolinium enhancement

NI-LVD non-inflammatory left ventricular dysfunction

NP natriuretic peptides

PD-1 programmed cell death receptor 1

TIL tumour-infiltrating T lymphocyte

TTE transthoracic echocardiography

Introduction

There has been a paradigm shift in the management of malignancy with the advent of novel immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies (CAR-T). In contrast to previous cancer treatments, immune-specific treatments unleash the patient’s own immunological armoury to battle a variety of tumours which progress in part by producing specific molecules to evade immune detection. The mechanism of action is by blocking specific receptors that inhibit the T cell (ICIs), or by genetically modifying the patient’s T cell to target the cancer cell (CAR-T). The development of this field is so exciting and promising that, in 2013, the journal “Science” named cancer immunotherapy its “Breakthrough of the Year”, based on therapeutic gains being made in ICI and CAR-T [1]. These treatments have dramatically increased survival in cancer patients such as in metastatic melanoma and acute lymphocytic leukaemia (ALL).

ICIs were first introduced in the year 2000 but it was not until 2011 that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted approval after two large phase 3 trials that showed the beneficial effects on patients with metastatic melanoma [2]. CAR-T cell therapy development followed, and the first CAR-T approved by the FDA was tisagenlecleucel, in August 2017, for the treatment of paediatric and young adult patients up to 25 years of age with B-cell ALL [3]. Given the positive results of both ICIs and CAR-T, the indications for their use continue to expand at an impressive pace. Currently, ICIs have been approved for use in multiple tumour types including malignant melanoma, squamous head and neck cell carcinoma, renal cell cancer, triple negative breast cancer and lung cancer [4]. CAR-T cell therapy has been approved for the treatment of children with ALL and adults with advanced refractory B-cell lymphoma. The number of patients receiving these treatments is rapidly increasing, and therefore so is the number of patients who develop cardiovascular adverse events, together with other immune-related adverse events (irAEs).

The aim of this article is to review the current literature on the mechanisms that underlie the cardiovascular toxicity of ICI and CAR-T cell therapy, describe the different manifestations of cardiovascular events that may arise from these treatments, summarise the diagnostic and treatment options available at the moment, and propose a practical way to assess these patients for general cardiologists, physicians, trainees, critical care staff, emergency/acute medicine staff and primary care doctors.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Mechanism of action: how do ICIs work?

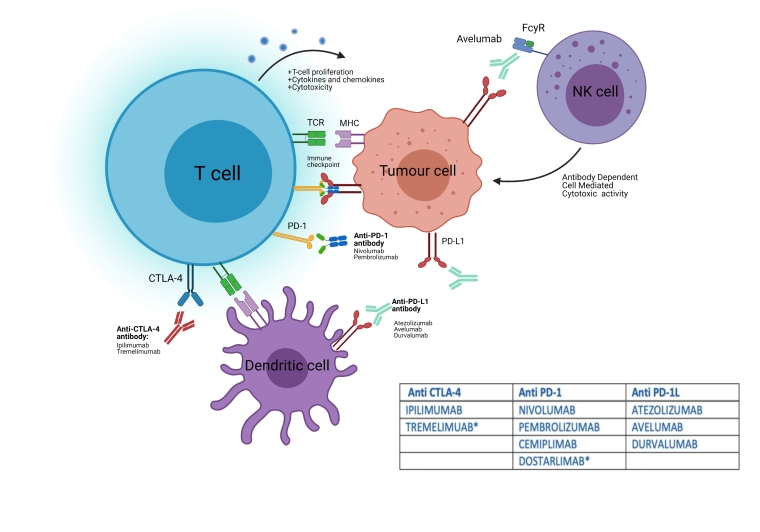

The T cell is the workhorse of the immune system. To prevent autoimmunity, it is necessary to keep this supreme immunity assassin in check by the use of “immune checkpoints”. These immune checkpoints are receptors which, when activated by binding to their corresponding ligand in the antigen presenting cell (APC), trigger an intracellular cascade that blocks the T cell immune response and provides peripheral immune tolerance. These receptors are also expressed by tumour cells, enabling them to evade immune detection [5]. There are multiple inhibitory checkpoint receptors found on the T cell. Treatments developed have targeted two main receptor pathways - CTLA-4 and programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1), as well as its ligand PD-L1 found on the cancer cell (Figure 1).

*Not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency.

CTLA-4: cytotoxic t-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; PD-1: programmed cell death receptor 1; PDL-1: programmed cell death ligand 1; TCR: T-cell receptor

Currently, the FDA and the European Medicines Agency has approved 7 different ICIs - ipilimumab (anti CTLA-4), nivolumab, pembrolizumab and cemiplimab (anti PD-1), and atezolizumab, avelumab and durvalumab (anti PD-L1) [4]. Other molecules such as tremelimumab (anti CTLA-4) and dostarlimab (anti PD-1), and inhibitors of other co-stimulatory T-cell pathways are under investigation.

Cardiovascular adverse events associated with ICIs

The mechanisms underlying ICI-related cardiotoxicity are not fully understood. One of the proposed explanations is that cells in the heart, including cardiomyocytes, might also express the PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways to prevent T cells from targeting the myocardium. Blocking these checkpoints might then lead to T-cell hyperactivation in the heart [6]. PD-1 has been known to be an important factor for the prevention of cardiac autoimmune disease since 2001, when Nishimura et al showed that genetically modified PD-1 knockout mice developed dilated cardiomyopathy [7].

James P. Allison, the pioneer of immunotherapy, presented a mouse model for ICI myocarditis. Gene loss of CTLA-4 led to premature death in half of the mice with associated myocardial infiltration by T cells and macrophages. Using this model, Allison and colleagues describe a mechanism by which myocarditis arises with increased frequency in the setting of combination ICI therapy [8].

The spectrum of cardiovascular adverse events related to the use of ICIs is broader than first described. Even though myocarditis remains the most frequent and serious event, other events such as atrial tachyarrhythmias, pericarditis, and non-inflammatory left ventricular dysfunction (NI-LVD) are now well recognised.

Myocarditis

Myocarditis is the most serious immune-related CV adverse event. Johnson et al published the first two case reports of fatal myocarditis in 2016 and concluded that this was a rare event (incidence <1%) with a high mortality (6/18 patients) [9]. Since then, the need to better identify, define and treat this disease has encouraged many cardio-oncology groups to investigate, resulting in several evidence-based publications.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of myocarditis is based on clinical examination, ECG, biomarkers, echocardiogram, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and, in some cases, endomyocardial biopsy (EMB). The ICI-related myocarditis clinical scenario ranges from a mild disease to a “fulminant” presentation. Symptoms can include palpitations, chest pain, signs of fluid overload or pulmonary oedema, and cardiogenic shock, or it can be asymptomatic. When a patient presents with any of these symptoms, the clinician should have a low threshold to suspect myocarditis and the diagnostic work-up should not be delayed. There are other factors that increase the clinical suspicion of myocarditis. Most cases occur in the first 4 cycles of ICI therapy, although delayed cases can occur. The presence of other irAEs increases the risk of developing a second irAE such as myocarditis, especially myasthenia gravis and myositis [10]. The other well recognised risk factor is the use of combination therapy, such as ipilimumab and nivolumab, where the synergistic effect further enhances antitumour activity but also increases the risk of irAEs.

ECG

An ECG should be performed in all patients with suspected ICI myocarditis. This can show tachyarrhythmias (ventricular and supraventricular), ST-T-wave abnormalities and PR prolongation (varying from new first degree heart block to complete heart block). QRS duration can be prolonged, something which has been associated with worse outcomes. Conversely, the QTc does not seem to be affected [11]. An ECG is crucial to rule out other diagnoses such as acute coronary syndrome; a normal ECG does not rule out myocarditis.

Cardiac biomarkers

Cardiac biomarkers, such as troponins and natriuretic peptides (NP), are very useful in this setting. Although troponin I and T are known to have similar sensitivity and specificity in acute coronary syndromes, increased troponin T in the context of myositis makes it less specific for the diagnosis of ICI-related myocarditis. In this scenario, high-sensitivity troponin I is recommended over troponin T.

NP are also commonly used to support the diagnosis of myocarditis, although their use is more limited by their low specificity, as this can be elevated in many other clinical settings, such as supraventricular arrhythmias, which may not be directly related to myocarditis. However, it is rare for NP to be normal in ICI-related myocarditis.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE)

Urgent cardiac imaging with TTE is indicated in any case of suspected myocarditis for assessment of left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction, regional wall motion abnormalities and pericardial effusion. Patients may present with preserved LV ejection fraction (EF); a normal echocardiogram does not rule out the diagnosis. More recently, global longitudinal strain (GLS) has been shown to be reduced in ICI myocarditis. GLS has a higher sensitivity compared to LVEF for diagnosis and offers prognostic value, as significantly lower GLS is associated with cardiovascular events in ICI myocarditis [12].

CMR

CMR provides the best myocardial tissue characterisation, hence it is the preferred imaging modality for diagnosis of ICI myocarditis. CMR is recommended in all suspected cases as it can confirm evidence of myocardial inflammation by demonstrating myocardial oedema and fibrosis using T2‐weighted imaging, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), extracellular volume fraction, T1 mapping, and T2 mapping [10].

EMB

EMB can provide a definitive diagnosis although, because of the patchy presentation of the myocardial injury, there is the potential for false negatives. Given the invasive nature of this technique, we recommend that it should not be used routinely; however, it is indicated when there is diagnostic uncertainty.

The diagnosis is critical to determine the safety to continue ICI therapy. Bonaca et al published a definition criterion for ICI-related myocarditis, grading the diagnostic likelihood into possible, probable or definite myocarditis [13] (Table 1).

Table 1. A proposed definition of myocarditis [13].

| DEFINITE MYOCARDITIS | PROBABLE MYOCARDITIS | POSSIBLE MYOCARDITIS |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Pathology | 1) Diagnostic CMR (no syndrome, ECG, biomarker) | 1) Suggestive CMR with no syndrome, ECG or biomarker |

| 2) Diagnostic CMR + syndrome + (biomarker or ECG) | 2) Suggestive CMR with either syndrome, ECG, or biomarker | 2) ECHO WMA with syndrome or ECG only |

| 3) ECHO WMA + syndrome + biomarker + ECG + negative angiography | 3) ECHO WMA and syndrome with either biomarker or ECG | 3) Elevated biomarker with syndrome or ECG and no alternative diagnosis |

| 4) Syndrome with PET scan evidence and no alternative diagnosis |

ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; PET: positron emission tomography; WMA: wall motion abnormality

Estimates of fatality in the region of 30-50% may underestimate real-world figures as studies implemented by cardio-oncology centres will provide gold standard cardiac care. However, with increasing recognition, absolute mortality may be falling (authors’ personal experience). This highlights the need for a global registry for cardiovascular irAEs.

Treatment

During suspicion or following a confirmed diagnosis of myocarditis, the prescribed ICI should be stopped. The first-line treatment for confirmed cases is high-dose intravenous steroids. The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) suggests promptly starting a regimen with methylprednisolone 1,000 mg/day followed by oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day [14]. We agree, and recommend, e.g., IV methylprednisolone 500-1,000 mg once daily for 3 days minimum and continuing until troponin stabilises at <80 ng/L and any clinical complications (heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias) have settled, and then switching to oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg. In cases refractory to corticosteroids the patient should be treated with mycophenolate mofetil or infliximab, special care being taken to avoid the latter in the case of signs of heart failure. The role of the CTLA-4 agonist abatacept is interesting and remains to be determined.

Non-inflammatory left ventricular dysfunction

This spectrum of ICI-related CV adverse events includes tachyarrhythmia and bradyarrhythmia, pericarditis, vasculitis, non-inflammatory left ventricular dysfunction (NI-LVD), Takotsubo-like syndrome, and acute coronary events, among others [15]. These differential diagnoses should be considered in cancer patients treated with ICI who develop new cardiovascular symptoms.

In our experience, NI-LVD occurs later in the time course of ICI treatment. The real incidence is currently unknown, but it has been reported that late cardiac toxicity secondary to ICI accounts for 1/3 of all the cardiac complications in ICI, and that NI-LVD is the most frequent event in this population [16]. In our clinical practice, we have seen that a significant number of patients develop this different type of cardiac injury characterised by a low EF (<50%), elevated NP but normal troponin levels, no evidence of myocardial inflammation on CMR, and no association with other concomitant irAEs (Andres et al, unpublished results). Patients who develop new LVD should be started on cardioprotective treatment following the current ESC acute and chronic heart failure guidelines [15].

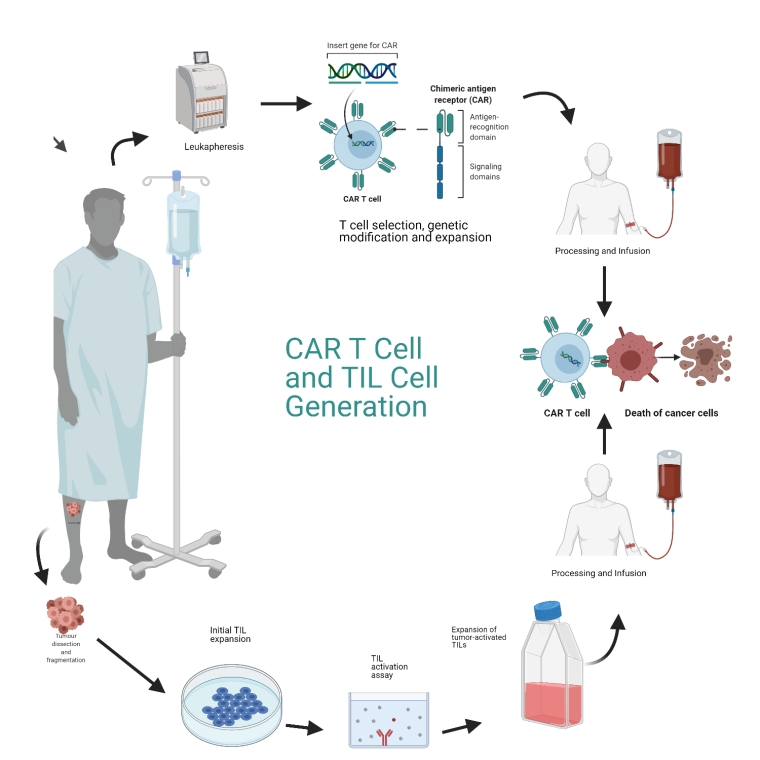

CAR-T and TIL cell therapy

Chimeric antigen receptor therapy (CAR-T), a gene-modified, adoptive T-cell immunotherapy treatment, represents a major advance in the management of relapsed or refractory haematological malignancies. These cells with genetically modified T-cell receptors have the focused specificity of a monoclonal antibody coupled with the cytolytic power of a T cell functioning independently of the major histocompatibility complex. The most common CAR-T is versus the B19 antigen of most B-cell malignancies (Figure 2).

CAR: chimeric antigen receptor; TIL: tumour-infiltrating T lymphocytes

During CAR-T therapy, T cells are collected from the patient, and the antigen receptor of the T cell is genetically reprogrammed against tumour antigens and reintroduced into the patient to trigger an amplified immune response against cancer cells.

An alternative immune cell therapy is tumour-infiltrating T lymphocyte (TIL) therapy. TILs are dissected out from a piece of tumour and are cultured in vitro bathed in high-dose interleukin-2. Once adequate numbers of TILs have been harvested, patients undergo lymphodepleting preparative chemotherapy prior to infusion of the TILs back into the tumour microenvironment. Subsequently, they are given a single infusion of high-dose IL-2. BiTEs are bispecific T-cell engagers – molecules with two different fragments from two different antibodies. These have the advantage of being “off the shelf” and can be manufactured to be given to all patients. They can be administered repeatedly, e.g., blinatumomab is CD19- and CD3-specific, leading to cytotoxic cell recognition (Figure 2).

There are several mechanisms for CAR-T cell-mediated cardiovascular toxicity. Firstly, there is an on-target, off-tumour hypothesis that was described by Linette et al who reported cardiogenic shock and death in two patients given CAR-T engineered to target the MAGE-A3 antigen in melanoma. It was found that this acute cardiotoxicity was due to off-target cross-reactivity against titin, a protein found in striated cardiac muscle with a protein similar to the antigen on MAGE-A3 [17].

Secondly, cardiovascular events can occur as a consequence of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) which, together with neurotoxicity, is the most common acute adverse event associated with CAR-T cell therapy. CRS is a systemic inflammatory response triggered by the release of immunomodulatory agents by CAR-T cells following their activation upon tumour recognition in vivo. CRS presents with fever, tachycardia, headache, tachypnoea, hypotension, rash and/or hypoxia. This can progress to circulatory shock, multiorgan failure and death. However, it is reversible if managed correctly. Serum IL‐6 levels are proportional to the severity of CRS; blockade with the anti-IL-6 receptor antibody tocilizumab can reverse the inflammatory response.

The grading system for CRS is based on the assessment of three vital signs - temperature, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. Patients presenting solely with fever are considered to have grade 1 CRS, whereas patients presenting with fever and hypotension and/or hypoxia requiring increasing amounts of vasopressors and/or oxygen supplementation are considered to have grades 2 to 4 CRS.

Myocarditis and cardiac injury are part of CRS secondary to CAR-T, and troponin rise and the amplitude of the troponin rise have prognostic value to predict mortality [18]. In a cohort of 137 adults receiving CAR-T, CRS occurred in 59% of patients, with 39% experiencing grade ≥2 severity. Seventeen patients experienced a major adverse CV complication, all in patients with CRS grade ≥2, and 95% of these patients had a troponin rise (Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between troponin elevation, grade of severity of CRS and cardiovascular events [19].

| CAR-T ADMINISTRATION | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CRS ≥2 | CRS<2 | ||

| TROPONIN + | TROPONIN - | TROPONIN + | TROPONIN - |

|

CV EVENTS (94%): CV mortality, HF, arrhythmias |

CV EVENTS (6%): HF decompensation |

NO CV EVENTS |

NO CV EVENTS |

CRS: cytokine release syndrome; CV: cardiovascular; HF: heart failure

The next challenge of immunotherapy is to increase on-target efficacy whilst decreasing the risk of off-tumour adverse events, as most of the tumour antigens are also expressed on normal tissue. Suicide genes have been proposed, which could be induced to arrest the effects of the CAR-T cells, to prevent extreme toxicity. More recently, in a paper by Mazzon and colleagues [19] have suggested a transient in vitro transcribed anti-mRNA-based CAR-T cell approach. The mRNA approach is hypothesised to provide a controlled cytotoxicity due to the short half-life of the mRNA.

Conclusion

We have reviewed the rise in use of ICIs, CAR-T and TIL therapies, their efficacy, and the cardiovascular complications caused by these therapies. Cardiovascular toxicities may present either early or late, in both the in-patient and out-patient setting with cardiovascular symptoms. A coordinated international process for recording the cardiovascular irAEs in a uniform global registry will allow more detailed reporting of events, and an understanding of the range of CV complications and the most effective treatments required.