Introduction

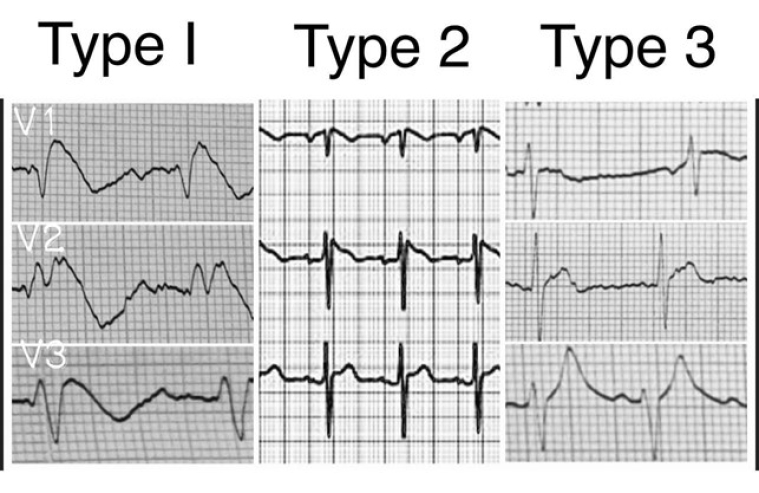

Brugada syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic arrhythmic disease. It is characterised by the presence of a typical electrocardiographic pattern (Figure 1) which can be of 3 different types and which is now called Brugada's sign.

The syndrome is named after a family of cardiologists who correlated the electrocardiographic sign with the arrhythmic syndrome which in some patients can cause severe arrhythmias and, in a small number of cases, can cause sudden cardiac death. The first description of the electrocardiographic pattern dates to 1953, when Osher and Wolff identified an electrocardiographic anomaly that simulated a myocardial infarction in a healthy male [1].

However, it was only in 1992 that the interest of the scientific community in this syndrome was aroused, when the Brugada brothers published data on 8 patients who died of sudden cardiac death with no apparent structural cardiac alterations or other known causes [2]. From 1992 onwards, the gradual diffusion of knowledge of Brugada syndrome among cardiologists and cardiology experts in general has caused a progressive and consistent increase in the number of diagnoses. Today, what was in the past a rare pathology and an unknown sign has become one of the most named and studied arrhythmic syndromes. This gradual sensibilisation has brought to light an increasing number of asymptomatic and non-familiar patients who present the electrocardiographic sign typical of Brugada syndrome but have not experienced any arrhythmic event for decades. These observations led to the distinction between Brugada sign and Brugada syndrome, causing a profound change in the approach of the scientific community towards the syndrome. In fact, although Brugada syndrome was previously related to sudden cardiac death or tachyarrhythmia, nowadays it is related to a specific electrocardiographic pattern which requires periodic monitoring.

Since 2015, the European guidelines on the prevention of sudden cardiac death have defined the risk of sudden death in Brugada syndrome as low [3].

Today, the real problem underlying the Brugada syndrome is to better understand which patients who display this sign will develop the syndrome and are actually at risk of sudden cardiac death.

History of the disease

Brugada syndrome manifests itself mainly by way of ventricular tachyarrhythmias which can often stop spontaneously in some cases by generating a syncope or, more rarely, can cause cardiac arrest. In some of these rare cases, cardiac arrest may be the first manifestation of the disease.

The first studies, which were published between 1998 and 2002 [4], showed a significant arrhythmic risk (about 30% at 3 years), even among asymptomatic carriers of the typical electrocardiographic pattern (type 1).

Initially, these data led to a very stringent medical approach that aimed at prevention. Consequently, extensive use has been made of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) for primary prevention.

Following the patients with implantable defibrillators over time, it has been progressively realised that most of them did not face sudden death and that device detection did not show the onset of relevant arrhythmic events over the years.

In epidemiological studies, sudden mortality data were significantly higher in the early registers. This phenomenon was probably due to the characteristics of the population enrolled in the tertiary referral centres to which the patient had access for previous arrhythmic events [5,6].

With the increasing number of patients identified and enrolled, ever closer to an unselected population, there was a progressive reduction in mortality and morbidity rates in the registers of Brugada syndrome [7,8].

The PRELUDE study reported an annual incidence of arrhythmic events of approximately 1% per year in asymptomatic patients with type 1 electrocardiogram patterns [7]. Sacher et al collected data from 166 asymptomatic people diagnosed with Brugada syndrome with an ICD followed for a period of 77 +/- 42 months. The study reported an annual incidence of appropriate defibrillator shocks of 1% per year [9]. In a recent meta-analysis of 13 studies that included 2,743 subjects, the annual incidence of arrhythmic events in asymptomatic patients was confirmed at 1% per year [10].

In the large FINGER registry cohort study, the incidence of arrhythmic events in asymptomatic individuals with the diagnostic Brugada pattern (type 1) was 0.5% per year [11]. These data suggest that the actual risk of cardiac arrest in asymptomatic patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome does not exceed 1% per year. However, even this estimate today appears very overestimated in the general population [12].

In 2018 a meta-analysis of 7 large prospective studies focused on the study of over 1,500 asymptomatic patients without ICD. Enrolled patients were at low risk (85% asymptomatic, and 50% with a drug test-induced type 1 pattern). In that study, the incidence of sudden cardiac death was found to be 0.38% per year in subjects with a spontaneous type 1 pattern and 0.06% per year in those who had a pharmacologically induced type 1 pattern [12].

Electrocardiogram

The ECG pattern was characterised by ST elevation in leads V1-V3 with an incomplete right bundle branch block appearance. These patterns may be present all the time or can appear only in response to particular drugs or, for example, as a consequence of a fever [3-12].

Three forms of the Brugada ECG pattern have been described [3,4].

Type 1: ST elevation with at least 2 mm J-point elevation and a gradually descending ST segment followed by a negative T-wave.

Type 2: at least 2 mm J-point elevation and at least 1 mm ST elevation with a positive or biphasic T-wave.

Type 3: less than 2 mm J-point elevation and less than 1 mm ST elevation.

Risk stratification

As can be seen from the above, it is important to try to identify parameters to select patients with higher mortality than normal subjects in the population of those with the Brugada sign (Table 1). The stratification of arrhythmic risk and sudden cardiac death in patients with Brugada syndrome is still an open question and remains a priority objective for many research groups.

Table 1. Risk stratification scale.

| Risk stratification marker | Grade |

|---|---|

| Male sex | ++ |

| Resuscitated cardiac arrest | +++ |

| Syncope | + |

| Familiar history | + |

| Spontaneous type 1 | ++ |

| Pharmacologically induced type 1 | + |

| Fragmented QRS | ++ |

| Early repolarisation | + |

| ST-segment elevation | ++ |

| Malignant arrhythmias | +++ |

| Genetic test | + |

| Electrophysiological study | + |

Studies conducted in recent years agree in highlighting that sudden cardiac death tends to occur mainly in affected males, with a risk 5.5 times higher than in females, in the third/fourth decade of life, and that it is rare in children and in the elderly.

The European guidelines [3] identify subjects who have already undergone resuscitated cardiac arrest (class I) and those who have syncope of a likely arrhythmic nature (class IIa) as being at high risk. In these subjects, an ICD is clearly indicated for secondary prevention. There are currently no indications in class I or II for ICD in primary prevention.

Other known risk factors which, considered individually, correlate with increased mortality are syncope, family history of sudden juvenile death and some electrocardiographic signs: fragmented QRS (with polyphasic aspects), the association with early repolarisation, the accentuation or occurrence of ST segment elevation in the recovery phase of an exercise test, the association with conduction disturbances (first- or second-degree atrioventricular block, right bundle branch block and/or hemiblocks).

However, although these factors statistically increase the risk of malignant arrhythmias, they are characterised by a low positive predictive value. In fact, among subjects with only one of these factors, very few events occur in the follow-up.

The genetic test is not useful for diagnosis since a genetic anomaly is found in no more than 30% of cases and has no prognostic value.

The electrophysiological study (EPS) has a class IIb indication.

Numerous controversies about its usefulness have divided the literature into two opposing camps between those who, like the Brugada brothers, consider it extremely useful and those who, like the Pavia research group, consider it useless.

In the midst of these two extreme positions, it is useful to consider how the heterogeneity of the stimulation protocols and the enrolled populations could explain the conflicting results of the different studies.

Recently, a multicentre study on over 1,300 published cases compared the results obtained based on the degree of aggressiveness of the stimulation protocols. The collected data suggest that arrhythmic risk correlates more closely with the EPS when low aggressive protocols are used [13].

The selection of subjects to undergo EPS also affects the predictive ability of the test: the history of syncope, the spontaneous type 1 pattern and the presence of symptoms are related to an increased predictive index, while the predictive value of the test was poor in asymptomatic or drug-induced type 1 subjects.

In recent years, score-based multiparametric models that consider anamnestic, clinical and integrated instrumental criteria have become increasingly popular. Finally, transcatheter ablation has recently been proposed for the treatment of Brugada syndrome. In 2015, for the first time, the group led by Professor Pappone identified a group of cells that express abnormal electrical potentials on the outer (epicardial) surface of the right ventricle. These cells are grouped in a confluent area, which has been found in all patients with Brugada syndrome. The research group reported that the most unstable arrhythmic substrate is associated with the clinical presentation of the most aggressive form of the disease and the development of malignant ventricular arrhythmias. It is possible to perform a targeted point-by-point radiofrequency ablation with a trans-pericardial approach and the use of dedicated software that are associated with mapping systems [14]. However, these results have not currently been confirmed by any other working group.

Brugada and sports eligibility

An open and still undefined challenge is that of fitness for competitive sports in patients with the Brugada sign. The limitation of physical activity in these patients has been the main cornerstone of preventive therapy for decades. However, the low incidence of sudden cardiac death in these subjects has gradually loosened this concept of prevention. Today, the new Italian COCIS protocols [15] and the European guidelines on the subject open up the possibility of carrying out competitive sports in some of these subjects.

From these guidelines we can draw the following indications:

Eligibility can be granted:

- in asymptomatic subjects with type 2 or 3 pattern in the absence of a family history of juvenile sudden death;

- in subjects with drug-induced type 1 without risk factors.

Eligibility may be reasonable in asymptomatic subjects with a spontaneous type 1 pattern, with no family history of sudden death or other minor risk factors and who have a negative EPS.

Eligibility should be denied:

- in subjects symptomatic of arrhythmic syncope with spontaneous or drug-induced type 1 pattern;

- in subjects with familial sudden death and with a spontaneous or drug-induced type 1 pattern.

The basis of this more open attitude that characterises the COCIS 2019 guidelines [15] derives from the following considerations. Malignant arrhythmias in Brugada syndrome typically appear at rest during bradycardia phases and, so far, there is no evidence that sport increases the risk of sudden death. It is hypothesised that the addition of a training-induced vagal tone may promote nocturnal arrhythmias. However, to date, there is still no evidence.

The European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) is also very open on the subject and even goes so far as to say that patients with symptomatic Brugada syndrome (syncope and/or sudden resuscitated cardiac death), after ICD implantation, if they are asymptomatic for at least three months and observing the necessary precautions, can practise all sports, even competitive ones, after a decision-making process shared between doctor and athlete [16]. Unlike the more open positions previously mentioned, the ESC guidelines have remained overly cautious in the indication for sporting activity in these patients, without being unbalanced [17].

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have not yet updated their guidelines. They date back to 2015 and conclude that Brugada athletes should be excluded from all competitive sports until a thorough evaluation by a cardiologist expert in arrhythmias has been completed, and the athlete and his family are well informed of the non-competitive risk [18].

Conclusion

All current cardiology societies mention in their guidelines how subjects with Brugada syndrome can be allowed to take part in all competitive sports only on condition that precautionary measures are taken, such as having a field doctor and external defibrillator ready, and that the subject should avoid drugs that worsen or dull the Brugada pattern and undergo an adequate intake of fluids and electrolytes to avoid dehydration. Also recommended are the prevention and timely treatment of hyperthermia from febrile or training-related illnesses, the possession of an automatic external defibrillator as part of the athlete's personal sports safety equipment and, finally, the definition of a training plan and emergency actions with school or team officials.

It is our opinion that such a lack of homogeneity of thought and such a variety of positions advise against recklessness and limit the possibility of practising sports only to truly low-risk patients and, even then, only after thorough screening and adequate advice.