Introduction

Key Message

Modern stroke care is an interdisciplinary challenge that needs the close collaboration of stroke physicians and cardiologists.

Stroke is the second leading cause of mortality and the most important cause of disability in adult life - often with dramatic effects on the patient’s daily life. It also poses a severe burden on families and on the healthcare system. Approximately 1.1 million people suffer a stroke each year in Europe and, with our ageing society and the anticipated further development of cardiovascular risk factors in our society, a further increase in stroke rates is predictable.

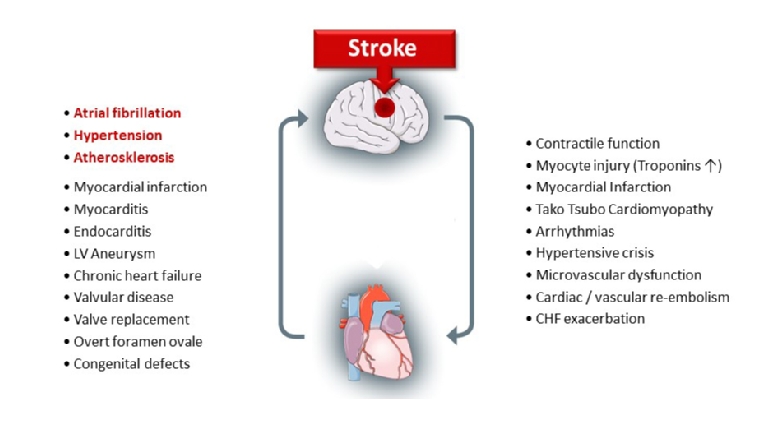

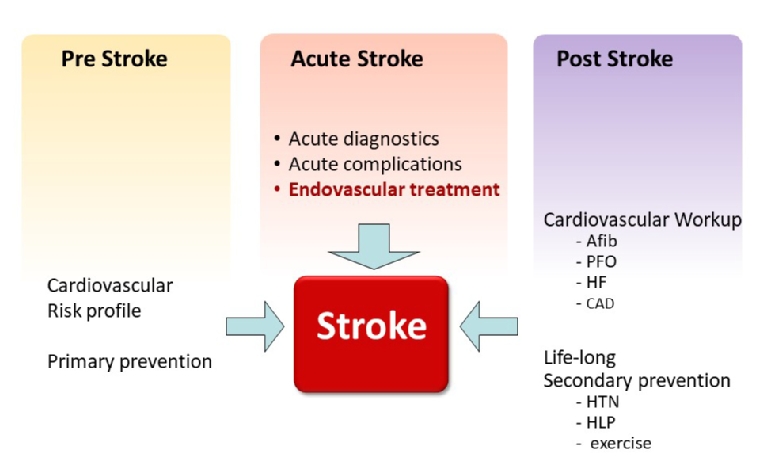

State-of-the-art stroke care is an interdisciplinary challenge. Given the close interaction of cardiovascular diseases with cerebral perfusion, it is obvious that a close collaboration of stroke physicians and cardiologists is needed. Virtually any cardiac pathology contributes to increasing the risk of stroke (Figure 1). In fact, often a stroke may be the first clinical appearance of a hitherto undetected cardiac problem. Therefore, a thorough cardiovascular diagnostic workup after a stroke is recommended in stroke patients. This may already begin in the subacute phase of stroke while the patients are still in hospital but, if not completed, it should be continued after discharge in the course of long-term post-stroke preventive care. Hence, a comprehensive understanding of stroke implications is needed among cardiologists to pursue adequate diagnostic workup of these patients.

Moreover, not only do heart diseases lead to an increased risk of stroke, but in turn the acute stroke may also account for cardiac injury via a range of neurohormonal and vegetative signals (Figure 1). These cardiovascular complications are challenging for doctors during the acute phase of stroke and often require the attendance of cardiologists in the stroke unit [1]. Modern stroke care requires interdisciplinary concepts, and a better understanding of and adherence to stroke care is needed for cardiologists [2]. The ESC Council on Stroke aims to promote awareness of stroke among cardiologists and to improve the involvement of cardiologists in state-of-the-art stroke care.

Clinical Principles of Stroke - What the Cardiologist Should Know

Key message

- The heart is one of the major sources of stroke. Almost all cardiac pathologies increase the risk of stroke.

- Key symptoms that demand immediate attention: face, arm, speech problems.

- ‘Time is brain’. Each minute delay causes substantial loss of cerebral function.

Aetiology of Stroke

Stroke is a clinical diagnosis that is based on sudden onset of symptoms of focal neurological dysfunction due to vascular damage of the brain [3]. Approximately 85% of all cases are ischaemic strokes and 15% are haemorrhagic strokes. Ischaemic stroke is caused by a critical reduction in cerebral blood flow. In the majority of cases, this is due to embolic occlusion of a cerebral artery (most often cardiac embolism, artery-to-artery embolism or less often aortic arch embolism or paradoxical embolism). In approximately 20-25% of ischaemic strokes the source of embolism remains uncertain despite diagnostic workup (so-called ‘embolic stroke of undetermined source’ [ESUS]) [4]. This is an important difference with acute coronary syndromes, which are rarely caused by coronary embolism. Atherothrombosis and small-vessel occlusion are further common causes. Moreover, reduced systemic perfusion due to hypotension may result in watershed infarcts in border-zone areas, especially with pre-existing stenosis of major cervical or cerebral arteries. In ischaemic stroke, a secondary bleeding in the infarcted area may typically occur (reperfusion injury) as a complication, called haemorrhagic transformation of an ischaemic stroke. In contrast, haemorrhagic strokes are caused by primary bleeding into the brain parenchyma (intracerebral haemorrhage) or in the subarachnoid space, typically from an arterial aneurysm (subarachnoid haemorrhage).

Classically, the diagnosis of stroke requires a duration of neurological dysfunction of at least 24 hours. The complete recovery from any symptoms in less than 24 hours was regarded as transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and was considered to leave no permanent cerebral damage. However, modern brain imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) frequently show evidence of morphological changes even after short-lasting neurological deficits. It is important to keep in mind that patients with TIA have a high risk of (early) stroke recurrence [5]. Therefore, particularly patients after TIA require rapid diagnostic workup for potential cardiovascular risk factors and respective treatment. The ABCD2 score (A=age >60 years, B=blood pressure >140/90 mmHg, C=clinical symptoms of unilateral weakness or speech disturbance, D=duration, D=presence of diabetes) is a fast screening tool to identify TIA patients with high risk of stroke recurrence (>5 points) who deserve rapid referral to a specialised centre [6].

Key Clinical Features that should Trigger a Stroke Alarm

Clinical presentation of stroke is highly heterogeneous because symptoms depend on the complex anatomy of the brain and the respective cerebral function of the injured brain region.

The most relevant symptoms are summarised in the FAST score (Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulties urge that it’s Time to call emergency services). This score was designed for rapid recognition of stroke, shows an acceptable accuracy and is frequently applied by paramedics in the field [7]. There are common key symptoms that may appear in isolation or in combination: unilateral weakness (including facial droop), unilateral sensory loss, speech disturbance (slurred speech or aphasia), visual impairment (monocular blindness due to retinal ischaemia, haemianopic visual field loss, and gaze palsy), visual-spatial-perceptual dysfunction, clumsiness or ataxia, gait disturbance and vertigo [8]. Several of these symptoms occur together and can be categorised as anterior circulation (via the carotid arteries) and posterior circulation (via vertebral arteries) syndromes. Knowledge of these syndromes is especially relevant when a patient presents with a normal examination but reports transient neurological deficits (i.e., TIA). Haemorrhagic stroke patients more often present with headache, but this clinical sign shows low specificity and should not be relied on.

Of note, approximately 25% of patients with suspected stroke will finally have an alternative diagnosis (so-called ‘stroke mimic’). Seizures, migraine with aura, syncope, acute vestibular syndrome, encephalopathies (e.g., septic), hypoglycaemia, or psychogenic deficits. Importantly, several studies have shown that thrombolysis in stroke-mimicking conditions is safe and should thus not be delayed if stroke is clinically suspected and brain imaging has ruled out haemorrhagic stroke and contraindications are cleared [9].

Stroke is a medical emergency that requires urgent clinical evaluation. In contrast to acute coronary syndrome, where myocardial ischaemia is the understood underlying patho-mechanism, in suspected stroke, rapid brain imaging is required prior to any therapy to differentiate between ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. This is usually done using non-contrast computed tomography.

Treatment of Acute Stroke

A key treatment principle of acute ischaemic stroke is rapid restoration of cerebral perfusion. For this purpose, intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue-plasminogen activator (rt-PA) and mechanical thrombectomy are evidence-based treatment options. Treatment with intravenous thrombolysis is approved within a time window of 4.5 hours of symptom onset (at a dose of 0.9 mg/kg to a 90 mg maximum; 10% as a bolus, 90% over 60 min; in Asia 0.6 mg/kg) [10]. Mechanical thrombectomy, a relatively novel treatment option, should be applied if there is evidence of a proximal vessel occlusion on imaging (strongest evidence for intracranial carotid artery and M1 segment of the middle cerebral artery) and should be offered within 6 hours of symptom onset. Both treatments lead to a marked increase in the proportion of patients without relevant disability at three months (number needed to treat [NNT] of 10 for rt-PA within 3 hours, NNT of 4 for mechanical thrombectomy for one patient with good outcome) [11]. Importantly, the efficacy of both treatments is highly time-dependent, which has led to the overarching principle of stroke treatment - ‘time is brain’. Recent trials have demonstrated that intravenous thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy may also be applied up to 24 hours from symptom onset in selected patients when modern multimodal neuroimaging criteria are applied [12].

Blood pressure control is important in acute stroke care. While careful lowering of blood pressure to <140 mmHg is indicated in patients with haemorrhagic stroke to reduce haematoma expansion and re-bleeding, in ischaemic stroke blood pressure should only be reduced if it exceeds 220/120 mmHg. Below these thresholds, high blood pressure is regarded as supportive to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure in the presence of ischaemia-induced cerebral oedema. If, however, thrombolytic treatment for ischaemic stroke is applied, moderate blood pressure lowering may be considered when blood pressure exceeds 185/110 mmHg to prevent haemorrhagic transformation [10].

Risk Factors of Stroke

Coronary artery disease and stroke share common risk factors; however, the relative impact of the individual risk factors is different. Ten key risk factors have been demonstrated to account for 90% of the population-attributable risk of stroke [13].

The most important risk factor for both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke is:

- hypertension.

Other key risk factors are:

- cardiac disease (especially atrial fibrillation)

- diabetes

- current smoking

- abdominal obesity

- unhealthy diet

- no regular physical activity

- alcohol consumption

- increased apolipoprotein ApoB/ApoA1 ratio

- psychosocial factors.

Notably, the most important risk factors include high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, physical inactivity, high cholesterol and diabetes which are all modifiable factors that could be targeted in preventive measures. Hypercholesterolaemia is a risk factor for ischaemic stroke; however, the impact is lower in stroke than in coronary heart disease, while low cholesterol levels increase the risk of haemorrhagic stroke.

Acute Stroke - Cardiologic Complications and Diagnostic Workup

Key Message

Thrombolysis and thrombectomy are causal therapies of ischaemic stroke but have limited applicability. Stroke unit care is the most widely applied treatment for stroke, targeting early secondary prevention and prevention of complications. Cardiologic complications are common and require regular involvement of cardiologic expertise in acute stroke care.

Fast restoration of cerebral perfusion and oxygen supply is the key concept of thrombolysis and thrombectomy therapy. These therapies are, however, available only for a small proportion of patients (up to 20% of patients are eligible for thrombolysis and <8% of patients for thrombectomy). Factors that limit the applicability of these causal therapies include the narrow time windows after symptom onset, multiple contraindications (particularly increased bleeding risks), limited availability or accessibility (thrombectomy) and failure of immediate recognition.

A major treatment concept which is eligible for all stroke patients is therefore the specialised monitoring of patients in dedicated stroke units. Stroke unit treatment is associated with lower rates of disability and mortality and should be offered to all patients diagnosed with stroke. The benefits of such specialised units are mainly derived from effective early secondary prevention and prevention of neurological and medical complications in the acute phase after stroke.

Cardiac Complications in Acute Stroke

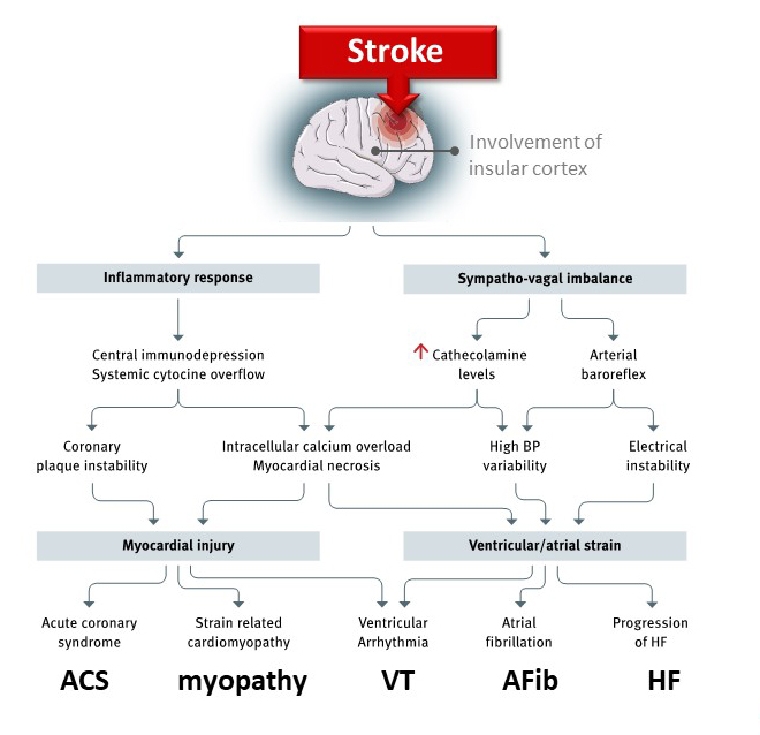

Cardiac complications are very common in the acute phase (24-72 h) after stroke, and cardiac monitoring may prevent aggravating and life-threatening situations. Those complications may arise from an imbalanced neuro-vegetative control of the cardiovascular system. Particularly when the insular region is involved in the brain injury, imbalances between the vagal and sympathetic systems may result in a range of cardiac and vascular complications (Figure 2).

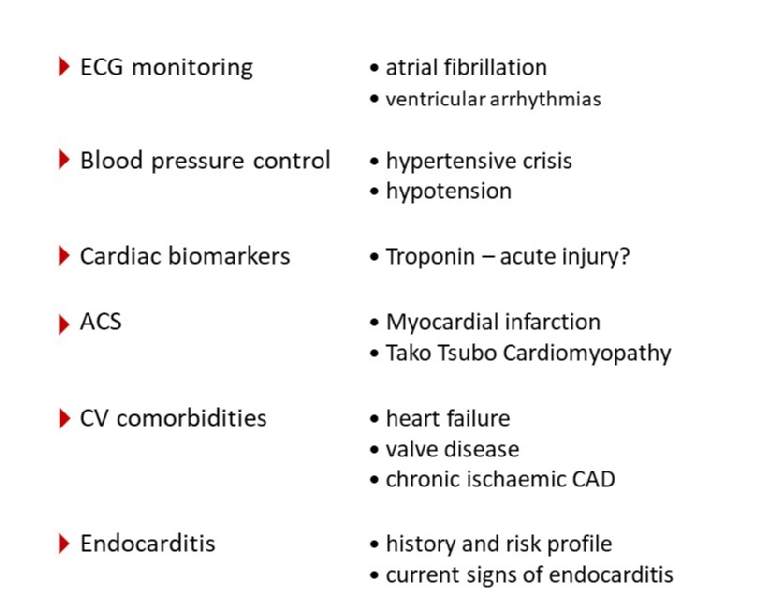

The term ‘stroke heart syndrome’ has been coined to address the characteristic interaction of brain injury and myocardial damage in acute stroke [15]. This includes supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, critical blood pressure peaks or lows, cardiac injury aggravating pre-existing heart failure or coronary syndrome (Figure 3) [2]. A direct myocardial injury with elevated troponin can be observed in up to 50% of patients with acute stroke using high-sensitivity assays [16]. These troponin elevations are usually moderate and only a fraction of patients with troponin elevation may eventually require further therapeutic measures for acute myocardial ischaemia [17]. The regular involvement of cardiologists is recommended to address these complications and promote further therapeutic measures if needed.

Cardiologic Diagnostic Workup After Acute Stroke

Diagnostic workup of stroke aetiology should be initiated in this early phase in order to tailor secondary prevention measures. Cardiac evaluation is mandatory in stroke patients. Standard cardiac workup includes ECG and troponin measurement, long-term ECG recording using Holter-ECG or continuous ECG monitoring on the Stroke Unit, and echocardiography [10]. The workup should also include cardiac imaging of brain-supplying vessels, cardiac evaluation (current and history), and stratification of cardiovascular risk factors.

ECG recording to detect atrial fibrillation (AF) as one of the most common causes of stroke is required with a minimum monitoring period of 24 hours. Longer monitoring should, however, be strongly considered in order to identify AF if no other obvious reason may explain the stroke event. A range of strategies for prolonged rhythm monitoring has been evaluated from repeated Holter monitoring to long-term rhythm monitoring using implanted loop recording devices. Prolonged ECG monitoring has been shown to result in higher rates of AF detection and anticoagulation initiation [18]. An obvious general rule can be applied that the longer the monitoring period is, the higher is the likelihood of detecting AF and of being able to initiate anticoagulation therapy in order to prevent recurrent strokes due to AF. In this regard, implanted loop recorders may be the ultimate approach to identify patients at risk [19].

Pre-existing cardiac conditions are not only important as an underlying cause of the index stroke and risk for recurrent strokes, but they are also relevant to increase the risk of complications in the current event. Therefore, the diagnostic workup of the cardiovascular condition has a high priority in patients with stroke. Echocardiography is in most cases essential to obtain essential information on cardiac function and morphology to evaluate the potential role of the heart in the stroke event. Notably, it is a common scenario that a stroke is the first clinical event of an underlying cardiac condition that has hitherto not been detected. Only after the index cerebral insult may proper cardiovascular workup unravel the cardiac condition so that adequate therapy can be established. It is important to confirm in dialogue with the stroke physician the question(s) to be addressed by the echocardiography and hence to decide on the appropriate echocardiographic method. Not every patient requires invasive (i.e., transoesophageal) echocardiography. Questions such as global myocardial function, regional ventricular wall contractility, wall thickness (indicative of pre-existing hypertension), regional and dimensions of ventricles and atria can best be evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography. More specific questions such as embolus formation in the left atrial appendage, detailed valve morphology, a persistent foramen ovale and the presence of infective endocarditis can only be addressed by transoesophageal echocardiography. Adequate assignment of the optimum method of echocardiography is not only a requirement to achieve the best possible diagnostic information but is also recommended to balance medical efforts as well as to minimise strain for the patients.

The Need for Long-term Cardiac Treatment after Stroke

Key Message

Patients after stroke require definite cardiovascular workup and long-term risk factor management. Most patients are, however, treated by their GP or lost to follow-up. Better long-term cardiovascular care of stroke patients and involvement of a cardiologist are required.

Secondary prevention after ischaemic stroke is based on continued medical therapy involving antithrombotic treatment, blood pressure control, lipid-lowering treatment, and control of blood sugar levels. Additional lifestyle measures such as smoking cessation, sufficient physical activity, and healthy diet are further factors to be monitored and advised in long-term cardiovascular prevention strategies. Early antithrombotic secondary prevention should be established as soon as possible after the diagnosis is made (exception - wait 24 hours if patient treated with rt-PA). Usually, antiplatelet therapy is established as first-line therapy in patients with ischaemic stroke. In patients with AF, oral anticoagulation can be initiated within 4-14 days after stroke depending on the size of the cerebral lesion. As mentioned before, hypertension is the most relevant risk factor for both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. Adequate individualised antihypertensive therapy and regular monitoring of the achieved treatment targets are a lifetime requirement.

Patients with ischaemic stroke should be treated with statins for lipid-lowering and plaque-stabilising purposes. There has been some controversy regarding statin treatment in patients with haemorrhagic stroke [20].

If specific cardiac conditions have been detected in the diagnostic process after stroke, subsequent therapeutic strategies need to be pursued. A persistent patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a relevant finding that may explain paradoxical embolisation in patients with ESUS or stroke of unknown origin. A number of clinical trials have recently confirmed the clinical benefit of therapeutic PFO occlusion in adequately selected patients (age 60 years or younger, PFO with right to left shunt, no other plausible cause of stroke identified). Other cardiac conditions (heart failure, myocardial ischaemia, valvular diseases, etc.) may be identified in the stroke workup that require adequate and continued therapy (Figure 4).

Concluding Comments

Stroke is currently regarded as an acute event and after the acute treatment most patients are sent back to their GP or lost to follow-up. By contrast, a long-term cardiovascular risk factor management for secondary prevention is needed. Stroke patients should be regarded as chronic patients who require long-term cardiovascular monitoring and treatment. Stroke is an interdisciplinary disease with the heart playing a central role as a causal and complicating factor in acute stroke. The contribution of cardiologists to comprehensive stroke care is required from a primary prevention perspective in the acute and subacute phases of stroke for diagnostic, monitoring and treatment purposes and in the long-term post-stroke care for definite cardiovascular therapies and risk factor management.

For all these aspects of stroke care, a better understanding of the stroke–heart interaction and consequent involvement of cardiologists in state-of-the-art stroke care is needed.