Introduction

Aortic valve disease includes aortic valve stenosis (AVS), aortic regurgitation (AR) and a combination of the two. The increased prevalence of non-rheumatic aortic valve disease parallels an increasingly ageing population. Degenerative AVS is the most common valvular heart disease and develops from fibrocalcific changes of the aortic valve cusps, resulting in reduced valve opening and eventually haemodynamic obstruction of the left ventricular outflow. Although a reported slight decline in AVS incidence suggested that improved cardiovascular risk factor control may limit the development of AVS in the Western world, cardiovascular prevention by means of lipid-lowering therapy has been shown to be inefficacious in reducing AVS progression. In addition to dyslipidaemia, other traditional cardiometabolic risk factors such as obesity [1-4], hypertension [3-6], and diabetes [3, 4, 6, 7], have also been shown to increase the risk of AVS in retrospective studies. Despite this shared risk factor profile and the common co-existence of atherosclerosis and valvular calcification, a substantial proportion of patients with AVS do not have concomitant coronary artery disease. Assessing the association of traditional cardiovascular risk factors with incident aortic valve disease is therefore important in order to identify potential preventive strategies in valvular heart disease. Identifying key risk factors for AVS may, in addition, provide clues for risk stratification and future interventional trials to slow down AVS progression and to avoid, or at least postpone, aortic valve interventions.

Aortic Stenosis Interventions

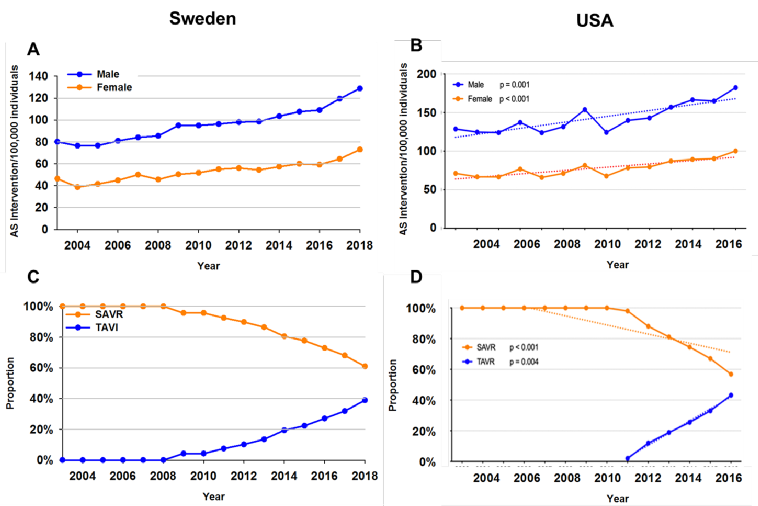

Over time, the number of aortic valve interventions has increased both in Europe (Figure 1A) and the USA (Figure 1B), with a decreasing proportion of surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in favour of transcatheter aortic valve implantation/replacement (TAVI/TAVR) (Figure 1C, Figure 1D). Although TAVI increased earlier in European than in American populations, the proportion of surgical to transcatheter aortic valve interventions now approaches 60:40 on both sides of the Atlantic (Figure 1C, Figure 1D) [8]. The striking sex differences in Figure 1A and Figure 1B in terms of the interventional management of AVS (at least in part) also illustrates the higher AVS incidence in males compared with females [1-4]. The inflation-adjusted annual expenditure of AVS interventions in the USA doubled between 2003 and 2016 [8]. In addition to avoiding periprocedural and postprocedural risks for AVS patients, the prevention of AVS incidence would hence also be anticipated to have substantial health economic benefits.

Figure 1. Aortic Valve Interventions Over Time in Sweden (left panels) and the USA (right panels). The upper panels show the number of aortic valve interventions in males (blue) and females (orange) per 100,000 individuals between 2003 and 2016/18. The lower panel show the proportion of surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR; orange) and transcatheter aortic valve implantation/replacement (TAVI/TAVR; blue), respectively.

Panels A and B represent data from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), accessed on 23/11/2019 at http://www.socialstyrelsen.se. Panels B and D from Alkhouli M, et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 [8] are reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology.

Lipids and Lipoproteins in Relation to AVS Risk

Observational studies have established an association of increased levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol with AVS. Likewise, a recent Mendelian randomisation study showed a positive association between genetically predicted LDL cholesterol levels and AVS [9]. However, large clinical trials revealed a lack of effect of statin treatment to decrease the haemodynamic progression of AVS. Whether these conflicting results represent pleiotropic effects of statins of which some may be detrimental for AVS or the lack of a causal effect of LDL cholesterol on AVS remains unclear. Other lipoproteins have attracted an increasing interest for their possible causal involvement in AVS. Lp(a) is an atherogenic lipoprotein that was identified as being genome-wide significantly associated with aortic valve calcification and AVS [10]. Mechanistic studies have also generated support to the importance of Lp(a) and Lp(a)-associated oxidised phospholipids in AVS pathophysiology [11]. Furthermore, increased Lp(a) levels in patients with AVS is an indicator of faster haemodynamic progression [12] as well as increased valve calcification activity as determined using the radiotracer [13] F-NaF for PET imaging [14]. Mendelian randomisation studies have associated elevated Lp(a) levels and corresponding genotypes with increased risk of AVS in the general population, with a 10% to 30% increase in the risk of AVS per 10 mg/dL increment of genetically predicted Lp(a) levels [15]. Compared with other cardiovascular outcomes, Lp(a) lowering could potentially prevent 1 in 7 cases of AVS compared with 1 in 14 cases of myocardial infarction [16]. Importantly, statins may not alter Lp(a) levels, which should be taken into account when considering the lack of beneficial effects obtained by LDL-lowering in AVS. Although it remains to be established whether these observations translate into a therapeutic value of Lp(a) lowering for slowing down AVS progression, Lp(a) could potentially also be considered as a biomarker to guide clinical follow-up, timing of intervention, and risk stratification in AVS patients.

Obesity

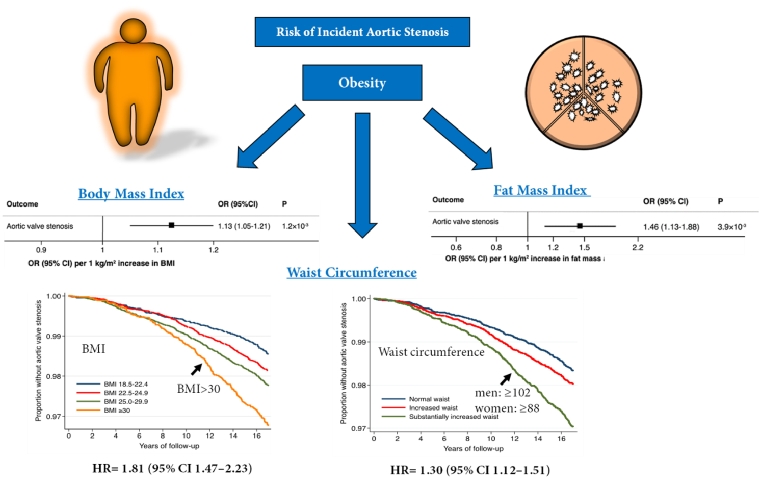

We recently reported that that body mass index (BMI) is associated with the risk of developing AVS (Figure 2). In brief, our analysis involved 71,817 men and women who were free of cardiovascular disease and followed for a mean of 15.3 years. AVS cases were ascertained through linkage with nationwide registers on hospitalisation and causes of death. Overweight and obese subjects had a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.24 (1.05–1.48) and 1.81 (1.47–2.23), respectively, for incident AVS. The highest risk of AVS was present in obese individuals with substantially increased waist circumference (WC), suggesting that the increased risk of AVS associated with overall obesity may be enhanced by an abdominal body fat distribution (Figure 2). Furthermore, the associations of BMI and WC with AVS persisted when the analysis was restricted to participants without a history of diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolaemia, suggesting that isolated obesity is also a risk factor, even in the absence of a metabolic syndrome. A Mendelian randomisation study subsequently established the causal relation of BMI with incident AVS [2]. In 367,703 UK Biobank participants [2], each 1 kg/m2 increase in genetically predicted BMI increased the risk of AVS by 13% (1.05–1.21), with an even stronger association for fat mass index (OR=1.46; 1.13–1.88) [2]. Interestingly, AVS exhibited the strongest association with BMI and fat mass index among the 14 examined cardiovascular disease outcomes, further reinforcing the strong connection between obesity and the risk of developing AVS, as depicted in Figure 2. We have estimated that up to 10% of AVS cases could be prevented if the entire population maintained a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or less [1].

Figure 2. Obesity Increases the Risk of Incident Aortic Stenosis. The association of body mass index (BMI), abdominal adiposity (waist circumference), and fat mass index with an increased risk of incident aortic valve stenosis. Modified from Larsson SC, et al. Eur Heart J. 2017 [1] and Larsson SC, et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 [2] by permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology.

Hypertension: Putting Pressure on the Aortic Valve

Hypertension is present in 21% of those with AVS, and 1.1% of hypertensive subjects have AVS [17]. However, only a few longitudinal studies have evaluated the association of hypertension with incident AVS [3, 5]. A recent cohort study of 5.4 million subjects followed for a median of 9.2 years through UK electronic healthcare records showed that elevated systolic blood pressure increased the risk of both AVS and AR with approximately 40% for each incremental 20 mmHg [5]. Diastolic and pulse pressures were also associated with an increased incidence of aortic valve disease [5]. It should also be considered that hypertension may affect the clinical presentation of AVS. Early detection and treatment of hypertension for the prevention of aortic valve disease therefore warrants further exploration in prospective, observational, and Mendelian randomisation studies.

Lifestyle Risk Factors

Since both obesity and hypertension are risk factors for AVS [1, 5, 6], additional benefit would be expected if physical activity leads to weight loss and reduced blood pressure. However, no significant association has hitherto been established between physical activity (assessed by questionnaire) and AVS risk [3, 18]. This may suggest that the effect of physical activity on the cardiovascular risk factors are too modest to provide a significant reduction in AVS incidence. Along the same line, diet influences cardiometabolic risk factors but no associations of overall healthy dietary patterns or major food groups with the risk of AVS have been reported [13]. Taken together, the effects of physical activity and diet on potential intermediates, including BMI, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolaemia, may not be sufficient to alter the risk of AVS. This is, however, in contrast to other cardiovascular outcomes, with inverse associations of healthy dietary patterns and physical activity and risk of myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke. Hence, the existing data today suggest that, although lifestyle interventions on diet and physical activity may be less likely to directly affect AVS, it appears reasonable to encourage physical activity and a healthy diet for AVS patients given the potential beneficial effects on other cardiovascular outcomes.

Similar to observations for other cardiovascular diseases, light-to-moderate alcohol consumption appears to be protective for valve calcification [19] and incident AVS [20]. Likewise, observational studies have found that current smoking is associated with a 30% to almost twofold increased risk of AVS [3, 4, 20], and a higher risk with increasing smoking intensity. Importantly, smoking being a modifiable risk factor for AVS is underlined by the time-dependent decrease in AVS risk in former smokers depending on the time passed since smoking cessation. This approaches the risk observed for never smokers after 10 non-smoking years [20].

Renal Function

A database study of serum creatinine measures from 1.1 million subjects revealed that decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was associated with an increased risk of incident AVS [21]. Compared with reference (GFR >90 ml/min/1.73 m2), even a slight decrease in kidney function (GFR 60-90) was associated with a 14% higher risk of developing AVS. This risk increased with decreasing kidney function reaching a 56% increased risk of incident AVS in subjects with a GFR <30. These results indicate that even relatively mild degrees of renal impairment increase the risk of developing AVS. Although the exact mechanistic link between chronic kidney disease and AVS remains unknown, changes in pro- and anti-calcifying factors and also effects on calcium/phosphate balance could be of importance and warrant further examination to establish possible measures for preventing AVS in chronic kidney disease.

Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was associated with an increased incident AVS in retrospective studies [3, 4, 6, 7]. Given the close connection between cardiometabolic risk factors, it is also important that obesity is taken into consideration as a possible confounder for the relationship between T2DM and AVS [7]. In mechanistic terms, it is also important to note that type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and T2DM exhibit similar patterns for increasing AVS risk, although the number of AVS cases was too low to establish any significant associations with T1DM in the only available study addressing that question [7]. Recent clinical trials have put the spotlight on the beneficial effects of anti-diabetic treatments on cardiovascular outcomes also in non-diabetic subjects, which would warrant further examination in AVS.

Conclusions

Today, the increasing burden of AVS and the resulting increased AVS interventions represent a burning clinical and health economic issue. Importantly, although the risk factor profile for AVS resembles that of coronary heart disease, there is also evidence of differential effects measures for the individual risk factors addressed. For example, whereas LDL-lowering by statin treatment did not slow down AVS progression in clinical trials, Lp(a) appears to be more strongly associated with the risk of AVS than with the risk of myocardial infraction [16]. Likewise, AVS ranked first in the increased cardiovascular risk associated with obesity [2]. There is an urgent need for prospectively evaluating the effects of risk modifications as well as treatments targeting the potential AVS risk factors. Examples of such therapeutic strategies could potentially include weight loss, Lp(a) lowering, smoking cessation, as well as antihypertensive and antidiabetic treatments. Deciphering the risk factors contributing to AVS incidence and progression will be key in designing preventive measures for slowing down AVS progression, and eventually preventing, or at least postponing, AVS interventions.