Introduction

In recent decades, e-Health has seen an unbelievable development, opening up new opportunities to physicians and patients in the management of many diseases. Many examples from the literature show an improvement in the quality of care and provide cost savings. Thanks to e-Health devices, a reduction of 35% in hospital admissions and 59% in readmissions was achieved in England.

The main “families” of e-Health tools are:

- Smartphone apps: ECG apps. ECG monitoring replacing Holter monitoring, blood pressure monitoring, multiparametric testing for heart failure (HF)

- Nanosensors: US microsensors, edible sensors (on pills to assess compliance)

- Lab-on-a-chip parameter systems: skin, breath gases

- Miniaturised systems: hand-held echocardiography. Tele-echocardiography.

Recently the acronym “Technology DREAM” has appeared, where the “dream” represents:

Diagnostic surveillance of chronic diseases

Referral for remote imaging and sensor data review

Education and engagement with social networks

Automated feedback for compliance or behavioural modification

Modelling advanced interventions.

For many years specific e-Health tools have been developed in the field of arrhythmic heart diseases. Arrhythmias have an often unpredictable onset, a very variable interval from one episode to another, and a variable duration. All of these features make it difficult to record an episode, even with repeated 24-hour Holter monitoring. To increase the likelihood of demonstrating an arrhythmia, in recent years two different non-invasive strategies have been introduced: a) prolonged continous or intermittent monitoring up to 30 days, which is useful also in patients with asymptomatic arrhythmias, and b) short recording for symptomatic episodes. Implantable loop recorders (ILR) are also widely used, but they are not within the scope of this review.

To offer an overview of the techniques and of the devices available for ambulatory ECG (AECG) monitoring, we performed a search in PubMed using the following keywords: ambulatory ECG monitoring, patch monitors, external loop recorders, event recorders, mobile cardiac telemetry, smartphone app. We also visited the websites of manufacturers.

Prolonged continuous or intermittent recording devices

In 1961, Norman J. Holter invented a 75-lb backpack with a reel-to-reel FM ECG tape recorder, analogue patient interface electronics, and large batteries. This was the first device able to record single-lead ECG for 24 hours during patient daily activities [1]. With improvements in technology and miniaturisation, 14-day continous recorders are now available. The number of leads has also increased from 2 to 12 to recognise the origin of arrhythmias and the ischaemia site better.

At present, 5 different monitoring techniques are available:

- The “classic” Holter monitoring, with the ability to record continuous 3- to 12-lead ECG signals simultaneously with a variety of other biological signals during normal daily activities.

- Patch ECG monitors which allow long-term recording of 14 days or longer.

- External loop recorders (ELR) of only selected ECG segments of fixed duration marked as events either automatically or manually by the patient. Some of them may generate an immediate alarm upon event detection.

- Event recorders selecting ECG segments of fixed duration after an event detection by the patient. Also, they can generate an immediate alarm upon event detection.

- Multilead mobile cardiac telemetry (MCT) may record pseudo-standard, 3-lead ECG. They can stream the data continuously to caregivers.

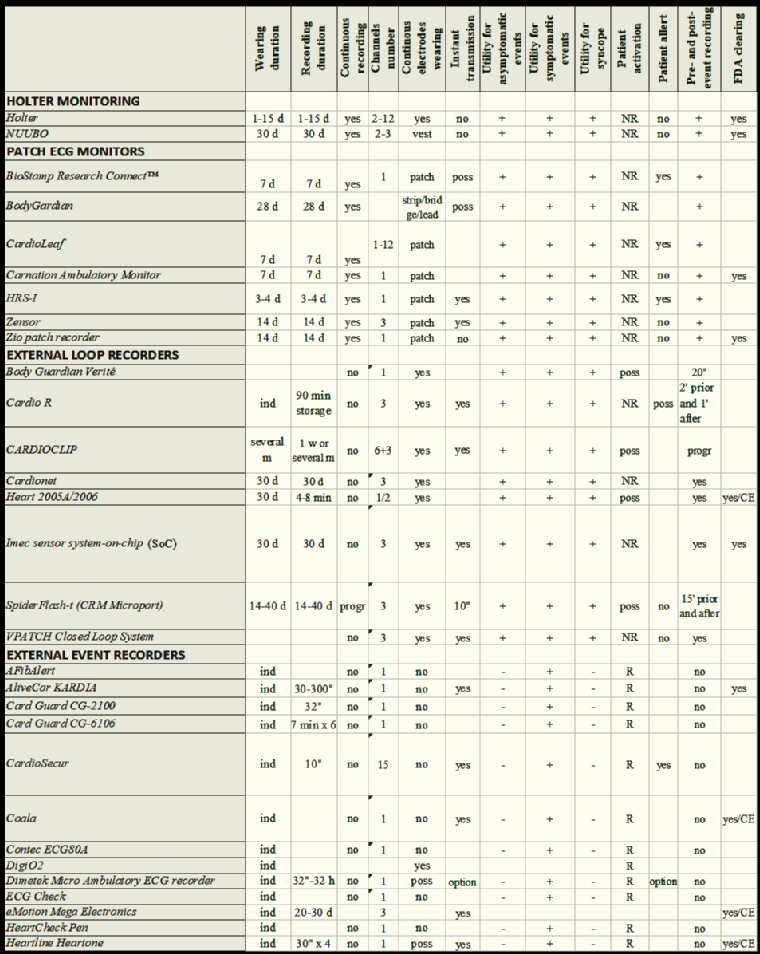

The features and the technical aspects of the different monitoring systems are shown in Table 1.

Clinical indications

AECG monitoring is traditionally indicated in patients with syncopes, palpitations, chest pain and coronary diseases. An increasing indication in recent years is the detection of asymptomatic atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with cryptogenic stroke [2].

Syncope

Syncope recurs after an unpredictable, generally long, time from the first episode. Extended recordings may improve diagnostic yield. Event recorders are not suitable in this setting, because during syncope the patient is unable to activate the device. One-month ECG loop recording use [3] increased the overall probability of obtaining a symptom–rhythm correlation to 56% as compared to 22% for 48-hr Holters. In another study, a loop recorder as first diagnostic strategy showed a symptom–rhythm correlation at a median time of 16 days and symptom–rhythm correlation in 87% of patients by one month of monitoring [4]. In a group of 85 patients implanted with an ILR, 59 (69%) had a diagnosis of their syncope at a median of 176 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 68–380 days), and 16 (27%) were diagnosed within 4 weeks after ILR implantation [5]. Therefore, ELR may be useful before ILR implantation. Consequently, a greater use of ELR may be justifiable to prevent the unnecessary use of ILR, which should be recommended if no diagnosis is obtained using ELR or if the frequency of symptoms is less than once per month. This strategy can minimise medical costs, enhance patient acceptance, and shorten the time to clinical diagnosis.

Palpitations

AECG monitoring is the key tool for the diagnosis of unexplained, well-tolerated recurrent palpitations. The device must be chosen according to clinical presentation and frequency of palpitations: a traditional AECG monitor (24–48 hr) is indicated for patients who experience frequent palpitations every day, or can reliably reproduce symptoms (e.g., positional or exertional palpitations). Event loop recorders and interactive ECG applications that save and transmit ECG only when the patient activates the monitor are suitable for patients with infrequent and unpredictable palpitations. Continuous loop recorders provided higher diagnostic yield, as compared to 24-hr Holter, and have proved to be more cost-effective [6]. It has been shown that two weeks of ECG monitoring provides the best balance between diagnostic yield and associated cost [7]. An external, patient-activated loop recorder can be used for an even longer time: in a group of 91 patients with palpitations, 51% of the ECGs were recorded within the first week after the device was handed out, and in 80% and 93% after 1 and 2 months. A follow-up of 2 months will suffice to establish a diagnosis in a large majority of this patient group [8].

The estimated diagnostic yield of different AECG recording modalities can be summarised as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Estimated diagnostic yield of different AECG recording modalities.

| Indication |

Event recorder <60” |

Standard Holter 24-48 hours |

Patch/vest/belt recorders/MCT/ELR |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | NA | NA | 3-7 days | 1-4 weeks |

| Palpitations | 50-60 | 10-15 | 50-70 | 70-85 |

| Syncope | Not applicable | 1-5 | 5-10 | 15-25 |

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cause of stroke in the elderly population. Almost 30% of all strokes remain without an identifiable cause after extensive workup and are thus referred to as “cryptogenic”. The recurrence rate of stroke is as high as 30%, mostly during the first year, and carries higher mortality rates. Occult paroxysmal AF seems to be one of the culprits of “cryptogenic” stroke and, due to the fact that asymptomatic AF is 12 times more frequent than symptomatic AF, detecting the arrhythmia in these patients is crucial. AF detection depends not only on monitoring duration, but also on the moment of the monitoring from the time of the stroke. In more than 50 studies, AF detection rates ranged from 0% with 24-hour Holter to >30% with ≥30-day monitoring. A meta-analysis of these studies showed that single time point screening (for 30-60 seconds) has an approximately 1% AF detection rate, which can be increased to around 5% when multiple recordings are performed. The authors noted that approximately 19 minutes of intermittent monitoring produced similar detection rates to conventional 24-hour continuous Holter monitoring [9].

Comparison of Holter to other recording modalities

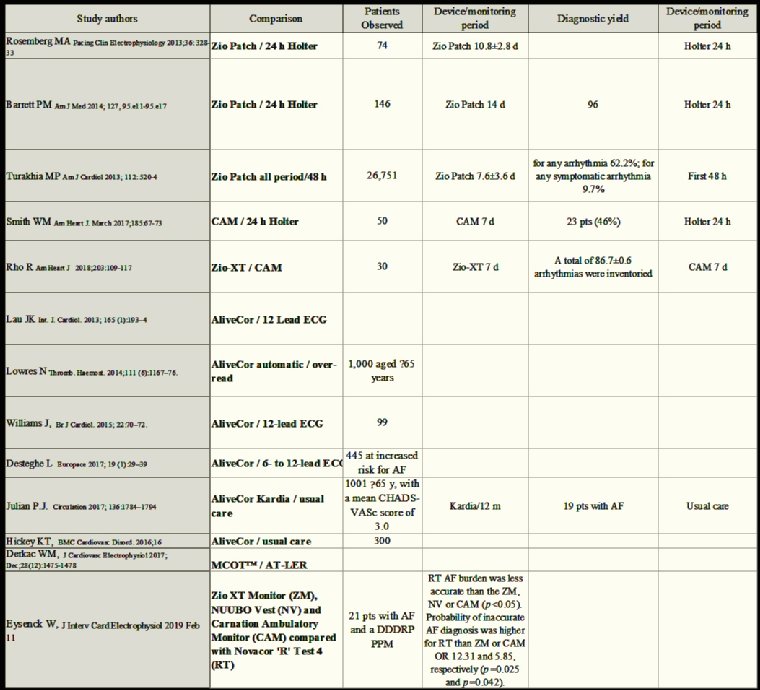

In Table 3 are summarised the most important studies analysing the comparison of different recording modalities with particular reference to their sensibility.

Pitfalls in the interpretation of arrhythmias detected by AECG and MCT

ECG artefacts can be related to body movement, temporary impairment of skin–electrode contact, lost electrode connections, dysfunctional leads, skeletal myopotentials, and ambient noise. These can generate deflections that can simulate a variety of atrial or ventricular arrhythmias. The majority of artefacts can be more easily recognised comparing simultaneous multichannel ECG. Failure by the technician or clinician to recognise a true arrhythmia episode in the ECG recording may lead to potentially more serious implications. Some primary care physicians cannot accurately detect AF on an ECG, as demonstrated by an analysis of 2,595 patients’ ECG from 49 general practitioners in central England participating in the SAFE study [10]. General practitioners misinterpreted (with or without the help of interpretive software) 8% of sinus rhythm as AF, and the probability that a positive diagnosis was correct was only 41%. Another study using a database from a US hospital which evaluated 2,298 ECGs (from 1,085 patients) with a computerised interpretation of AF found that ECGs from 382 patients (35%) had been misinterpreted; physicians did not correct the computerised misinterpretation and initiated inappropriate and potentially harmful treatments, and they pursued unnecessary additional testing for 92 patients (8.5%). This problem is common and highlights the need for improved training of the dedicated staff in the interpretation of AECG in order to avoid errors.

Legal considerations

Prolonged ambulatory ECG monitoring systems are very useful tools to detect arrhythmias and to improve diagnosis, but they are not emergency devices: this should be clear to all patients undergoing these evaluations. Centres receiving wireless ECG transmissions have mechanisms to handle incoming data on a 24/7/365 basis to ensure that potentially life-threatening arrhythmias are rapidly identified and treated. However, even with real-time transmission of the ECG signals, alerting emergency medical services to intervene in a few minutes is impossible, e.g., given the difficulty in localising where the patient is at the moment of the arrhythmic event. Moreover, as patients are monitored for up to a month at a time, a significant amount of ECG data accumulates for physician review.

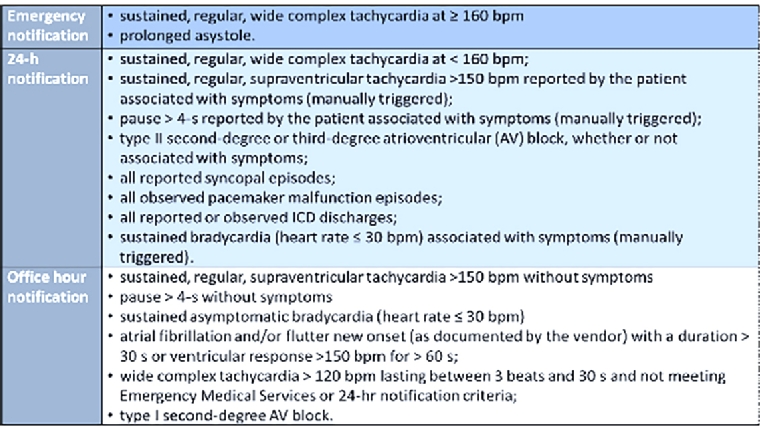

Vendors have established nominal, shared, physician notification criteria (emergency, 24-hour and office notification criteria) [2], as reported in Figure 1.

Smartphone and smartwatch technology

The newest generation of smartphone is equipped with photoplethysmography (PPG).

Using light beams and light-sensitive sensors on the smartwatch or smartphone, changes in the blood volume through the wrist or a finger tip are measured to generate a PPG, used to estimate the heart rate and to classify rhythm as regular or irregular, to detect AF.

The accuracy of the Cardiio application (Cardiio, Cambridge, MA, USA) to detect AF was shown in 1,013 patients with known hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and/or aged >65 years [11]. Each PPG waveform recording lasted 17.1 seconds. A diagnosis of AF was produced if at least 2 of 3 PPG recordings were classified as “Irregular.” The detection of AF was based on a lack of repeating patterns in the PPG waveform due to AF. The sensitivity and specificity of Cardiio Rhythm for AF detection was 92.9% (95% CI: 77-99%) and 97.7% (95% CI: 97-99%), respectively, suggesting the application’s reliability to detect AF in patients at risk.

The Cardio and Motion Monitoring Module (CM3 Generation-3; Philips, Best, the Netherlands) includes a PPG sensor and an accelerometer to measure cardiac rhythm and body motion. The algorithm used to analyse pulse data from this wrist-based wearable device can accurately detect pulse irregularities attributable to AF with >96% accuracy (ECV, sensitivity=97%; HOL, sensitivity=93%; both with specificity=100%). In healthy subjects, the Markov model algorithm detected only 0.2% false-positive AF [12].

In the WATCH-AF trial [13], a Gear Fit2 smartwatch (Samsung Electronics, Suwon-si, South Korea) with a study version of the Heartbeats application (Preventicus, Jena, Germany) demonstrated a sensitivity of 93.7% (95% CI: 89.8% to 96.4%) and a specificity of 98.2% (95% CI: 95.8% to 99.4%) for AF detection with excellent positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs) of 97.8% (95% CI: 94.9% to 99.3%) and 94.7% (95% CI: 91.4% to 97.0%), respectively, as well as an excellent overall accuracy of 96.1%. False-positive results were observed in 1.0% (5 of 508) and false-negative results in 3.0% (15 of 508).

The Apple watch study was a prospective, single-arm, open-label study with 419,297 participants evaluating the ability of an irregular pulse detection and irregular pulse notification algorithm to identify AF by the Apple watch [14]. When a tachogram detects an irregular heart rate, the algorithm gets 4 confirmatory tachograms with irregular pulse rates during minimal arm movements. After these 4 confirmatory tachograms the participant receives a phone notification. About 2,161 (0.52%) people were notified; 658 got an ECG confirmatory patch but only 450 returned it for analysis. AF was detected in 34% of the cohort receiving the notification and wearing the ECG patch. The PPG technology used in the Apple watch validated by concurrent use of the ECG patch showed a PPV of the tachograms of 0.71 (95% CI: 0.69–0.74), and a PPV of notifications, triggered by 5 tachograms, of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.76–0.92).

Implications and threats

The ubiquitous presence of smartphones and free downloadable healthcare apps has the potential to be widely used and for unrestricted periods of time. Validation of recordings will be challenging, with the risk of self-diagnosing arrhythmias and self-medication with anti-arrhythmic drugs and severe pro-arrhythmic risks.

Anxiety associated with arrhythmia recording can be a great issue in some patients, but for the moment there are no studies addressing this topic. Only the SAFE study assessed anxiety associated in the particular setting of AF screening and provided limited evidence showing that anxiety scores were not significantly different for systematic and opportunistic screening groups after screening or after 17 months.

Some patients may have psychoneurotic behaviour related to the smartphone apps, with an excessive focus on their condition, with many controls a day of their AECG, with loss of a normal life capacity and a reduction of their quality of life, in a scenario similar to that observed with blood pressure home monitoring.

Effectively, a clinical study should be planned about this issue in a large population, to discover possibly surprising results.

However, there are many potential benefits of involving patients in their healthcare process, increasing their engagement and compliance with medical therapies and follow-up management.

A regulatory framework of these consumer-grade devices used in a clinical context, coupled with clinician education about risks and limitations, is necessary to avoid inappropriate reliance and to ensure that medically approved AECG monitoring is used when appropriate.

As the wear time of AECG devices increases due to technological enhancements, the yield of detected arrhythmias is expected to increase proportionally.

As newer devices detect shorter and shorter arrhythmia episodes over longer monitoring periods, the clinical significance of these episodes may be uncertain, because they were obtained outside randomised clinical trials. Physicians will have much more difficulty in deciding whether to start treatments such as anticoagulation or antiarrhythmics. Improved decision models are needed to help clinician decision making.

Also, more robust, individually tailored estimates of long-term and short-term risks of events and potential benefits and harms of therapies have to be stated.

Conclusions

The increasing need for monitoring patients with palpitations, syncopes and cryptogenic stroke has occurred at a time when we see a clear evolution and improvement in the accuracy and efficacy technology of the recording devices themselves. Besides the traditional 24- to 48-hour Holter monitoring, we can now use patch ECG monitors, external loop recorders, event recorders (including smartphones) and mobile cardiac telemetry.

Knowledge of the characteristics of all these groups of devices is crucial in order to choose the appropriate one for each patient’s need.

24- to 48-hour Holter is useful for patients with frequent and reproducible palpitation: continuous monitoring can be helpful to characterise rhythm before arrhythmia onset and 12-lead recorders can recognise the origin of arrhythmias better. Only in 1-5% of cases they can suggest the cause of syncope, and they can detect AF in only 3-5% of cryptogenic stroke. Thirty-day vest/belt recorders improve syncope and AF detection to 27% and 21-30%, respectively.

Patch ECG monitors allow up to 14 days of continous recording and some of them can wireless transmit ECG with a diagnostic yeld of up to 70% for palpitations and 10% for syncopes.

External loop recorders analyse 1 to 3 ECG-lead rhythm and store up to ten different arrhythmias with some minutes before and some minutes after the episode. Due to intermittent monitoring, they can work for up to one month.

Event recorders are generally simpler and less expensive devices, that must be activated by the patient when a symptom occurs. They can be worn for a longer time but are not suitable to document syncope cause or to record asymptomatic arrhythmias.

Mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry devices can stream the data continuously to caregivers.

Some devices combine the functionality of traditional 3-lead Holter and event and loop recorders, programmed to autodetect and autosend events at a certain time, making it impossible to classify them into only one group.

All these new AECG monitoring devices are changing our working attitudes and habits, requiring new legal and scientific rules. Studies are needed to guide implementation of this technology into health care.

Doctors and patients have to be trained for the appropriate use and application of these devices to avoid potentially dangerous misuse and to be able to understand correctly the clinical meaning of what each device is able to do.