Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is an irreversible dilatation of the infrarenal abdominal aorta greater than 3.0 cm in diameter, more common in the elderly male population.

Ninety percent of all AAAs are degenerative and fusiform, located in the infrarenal aorta, often associated with iliac dilatating and occlusive disease; proximally, it may extend to involve the origin of the renal and visceral arteries and can coexist with peripheral aneurysms, especially in the popliteal arteries.

Aortic dissection, connective tissue disorders such as Marfan’s and Ehler-Danlos syndrome, and inflammatory aortitis such as Takayasu’s disease are other possible aetiologies with extensive involvement of the thoracic and suprarenal aorta; bacterial infection leading to focal weakness areas in the aortic wall may cause AAA, usually saccular rather than the normal fusiform dilatation. Persistent smoking is associated with its progression, and peripheral, visceral and coronary artery disease often coexist; therefore, AAA should also be considered a marker of advanced cardiovascular disease [1].

The majority of AAAs are asymptomatic; symptoms such as abdominal pain and tenderness over the aneurysm may result from its expansion and from compression of adjacent structures and are an indication for prompt treatment. Rupture of an AAA is a surgical emergency and immediate repair must be offered.

Planning of AAA repair, either by open surgical repair (OSR) or endovascular aortic repair (EVAR), requires: i) dedicated full aortic imaging with multiplanar computed tomography angiography (CTA) and curved three-dimensional vascular reconstructions plus femoropopliteal assessment as the presence of synchronous aortic and/or peripheral aneurysms is not uncommon, and ii) complete clinical assessment and risk stratification, as mentioned elsewhere.

This paper will focus on the controversy between OSR and EVAR for intact and ruptured AAAs and how to offer the best and most durable treatment based on our practice and published scientific evidence.

Repair for abdominal aortic aneurysms

Indications for treatment

The indication for repair in asymptomatic fusiform aneurysms is mainly related to its maximal diameter (men >55 mm; women >50 mm) [2]; patients with rapid growth rates (greater than 10 mm/year), saccular aneurysms, family history of ruptured AAA and infectious aneurysms should be offered repair independently of aneurysm size. Informed discussion on overall surgical risk, life expectancy of the individual patient and expected procedural outcomes is necessary for the patient’s informed consent to treatment [1]. In the presence of aneurysm-related symptoms such as pain and tenderness on palpation, prompt intervention can be indicated irrespective of the aneurysm size.

Open surgical repair (OSR)

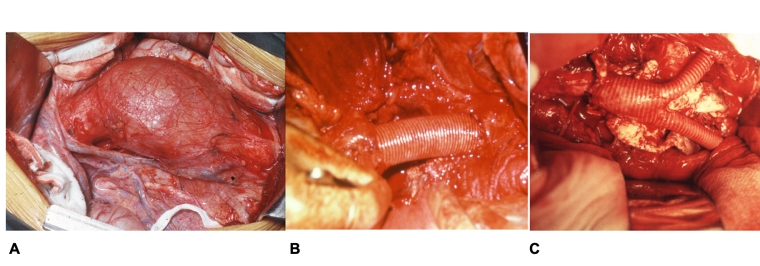

OSR requires general anaesthesia, laparotomy through midline incision from the xiphoid to the pubis to allow transperitoneal exposure of the aorta or a left side abdominal incision for a retroperitoneal approach. Full aortic exposure and mobilisation are necessary to achieve proximal aortic control, either by infrarenal, suprarenal or supra-celiac aortic cross-clamping and iliac dissection to obtain distal control. The diseased aortic segment is partially resected, and interposition of a prosthetic graft is used to maintain aortic continuity. Proximal graft anastomosis is usually performed distal to the renal arteries but may include them plus the visceral arteries if the aneurysm extends proximally; graft configuration can be aorto-aortic, aorto-bi-iliac or aorto-bifemoral according to the distal extension of the aneurysm and presence of concomitant occlusive disease in the iliac arteries (Figure 1). Preservation of blood flow to one hypogastric artery is essential, in order to prevent left colonic and pelvic ischaemia, late buttock claudication and sexual dysfunction, often associated also with dissection of the neural plexus around the aortic bifurcation and left common iliac artery.

OSR has a mortality rate ranging from 3 to 5%, non-negligible surgical morbidity, and long hospital stays but rare long-term aneurysm-related complications and reduced need of reinterventions in patients surviving the operation [1].

Late complications of OSR are under-reported. Aneurysmal progression in more proximal segments of the aorta plus graft-related problems such as thrombosis, development of false aneurysms, aorto-enteric fistulae and graft infections have been recognised [3]. Laparotomy-related events such as incisional hernias and bowel adhesions leading to mechanical intestinal obstruction requiring surgical treatment are not uncommon.

Endovascular repair (EVAR)

In EVAR the aim is to exclude the aortic aneurysm from systemic circulation through a stent graft introduced remotely via the femoral arteries. To achieve adequate exclusion suitable the anatomy should be suitable for adequate sealing and fixation of the graft fabric at proximal and distal anchoring segments - landing zones - thus reducing the risk of graft migration.

The proximal landing zone - aortic neck - is defined as having a non-dilated diameter <30 mm, a thrombus-free aortic segment between the lowest renal artery and the aneurysm with a length of at least 10-15 mm, angulation <60º and absence of circumferential calcification. The distal iliac landing zone also requires a disease-free segment of at least 10-15 mm in length and <20 mm in diameter, usually on the common iliac arteries, in order to preserve flow in both external iliac and hypogastric arteries [1,4]. Preservation of at least one open and functioning hypogastric artery is also a main requirement to prevent pelvic and colonic ischaemia as in OSR.

Most stent grafts nowadays have modular designs with two or three separate components including an aortic bifurcated main body and one or two iliac limbs. Specific anatomic criteria for each endograft design are based on proximal and distal neck length, diameter and angulation and constitute a set of rules known as instructions for use (IFU); non-compliance with them is associated with higher complication rates [1].

Adequate proximal and distal fixation and sealing are major determinants for successful exclusion of the aneurysm; aortic neck shape (cylindrical, conical, funnel- or barrel-shaped), presence of thrombus and calcification, in addition to length, diameter and angulation, have an impact on the immediate success and long-term durability of EVAR. Proximal uncovered stents improve fixation proximal to the renal arteries without compromising renal flow.

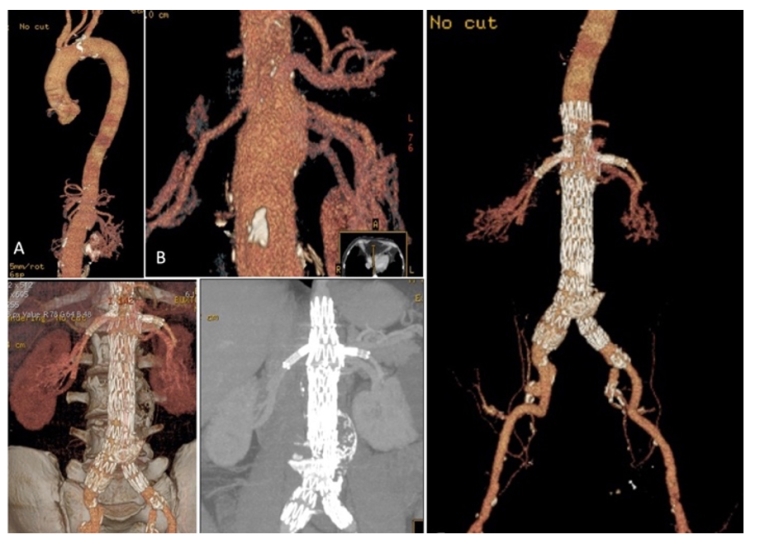

Custom-made fenestrated/branched grafts to accommodate visceral arterial ostia and parallel-graft technology allow proximal extension of the aortic sealing and fixation by incorporating the renal and visceral arteries preserving their flow [4]. They extend the applicability of EVAR to short neck AAA, juxtarenal or pararenal AAA. Figure 2A shows the case of a patient with a pararenal aortic aneurysm successfully treated with double fenestration for the renal arteries and a scallop for the superior mesenteric artery, without complications and full exclusion of the aneurysm eight years later.

Distal sealing is usually obtained at the common iliac arteries provided there is no iliac dilatation. Extension of the graft limb to the external iliac artery with exclusion of the hypogastric artery increases the risk of pelvic and bowel ischaemia and later buttock claudication and sexual dysfunction, especially if bilateral hypogastric exclusion was performed. Spinal cord ischaemia may occur in this setting, but it is a very rare event in abdominal aneurysm repair. Branched grafts to the hypogastric arteries - iliac branched device (IBD) - overcome this limitation preserving both external iliac and hypogastric arterial flow [1]. Commercially available IBDs provide safe and durable procedures. This is documented in Figure 2B showing a severely diseased patient with complex aneurysmal anatomy requiring exclusion of a 9 cm diameter left iliac aneurysm and an IBD on the right iliac axis for a smaller iliac aneurysm, preserving flow in the distal hypogastric artery.

Reported early and late EVAR failures are associated with endoleaks - known as the Achilles’ heel of EVAR - causing reperfusion with pressurisation of the aneurysm and increasing the risk of its rupture. There are four main types of endoleak: type I due to inadequate sealing at the aortic neck or at the iliac landing zone; type II from collateral branches such as patent inferior mesenteric or lumbar arteries; type III from disconnection of modular components of the stent graft; and type IV with persistent leakage through the endograft fabric. Other causes of failure include stent graft migration, limb occlusion and infection.

A lifelong surveillance programme is mandatory for all EVAR patients to detect early and late complications and to reduce late ruptures [1].

Which strategy for treatment: OSR or EVAR? What is the present evidence?

A. Intact aneurysms, defined by the absence of rupture on CT scan.

The choice between OSR or EVAR should be individualised; it requires full aortic evaluation with CTA, carefully balancing between the risks and benefits of both techniques, and institutional experience, as in the majority of patients both treatment strategies could be applicable.

Four randomised controlled trials have compared elective EVAR to OSR [5-8] but only two [5,6] published results with more than 10 years of follow-up; data from these four different trials were pooled and analysed [9], providing a total of 2,783 randomised patients, and 14,245 person-years. The evidence can be summarised as follows:

- Threefold reduction in 30-day/hospital mortality in EVAR and improved early survival and reduced all-cause and aneurysm-related mortality in the EVAR group in the first six months.

- Loss of the initial benefit on survival and AAA-related mortality at four years in the EVAR group associated with an increased need for reinterventions.

- The most common complications following EVAR were type II endoleaks (11.7%), followed by type I and III endoleaks. Its clinical significance depended on its effect on continuing growth of the aneurysm sac. The majority of type II endoleaks can be transient; only a smaller percentage is associated with increased aneurysm size as opposed to types I and III where progression of the aneurysm occurs, potentially leading to secondary ruptures.

- Higher frequency of reinterventions in the EVAR group with an impact on mortality; the earlier its performance, the greater the negative impact on the patient’s survival.

- Only 65.8% of type I endoleaks were treated, and early corrections of EVAR-related complications were performed in less than two thirds of the patients, which could explain the observed effect on late mortality.

- Reduced number of patients with complete late follow-up and under-reported objective assessment following OSR.

For severely ill patients not fit for open surgery, the EVAR-2 trial suggested no benefit on midterm survival after EVAR [10].

Are these observations still valid in today’s practice?

No patients were enrolled later than 2008 (12 years ago) in these published randomised controlled trials (RCT). During this period, EVAR technology improved, more accurate selection criteria were defined, and there was increased awareness of IFU as well as more liberal use of strategies to overcome unfavourable anatomy proximally and distally and compliance to structured surveillance programmes for early recognition and timely repair of EVAR complications. Also, a very small number of female patients was enrolled (less than 1% in two trials) [7,8], plus there was a lower prevalence of concomitant severe conditions when compared to the real world and incomplete discrimination of relevant anatomic characteristics such as tortuosity, type and extension of calcification, presence of underlying thrombus, iliac bifurcation diameter and patency of the inferior mesenteric artery.

Evidence from a recent systematic review and meta-analyses [11,12] pooling all available data to compare long-term outcomes following EVAR or OSR for AAAs, at 5- to 9-year follow-up in patients recruited after 2010 (modern endografts), showed no significant difference in long-term survival after 10 years, but the EVAR group continued to present higher long-term and very long-term reintervention rates and late ruptures than the OSR group [11]. Early benefit of EVAR over OSR (0-2 years) but no difference in the long-term (6-10 years) and very long-term mortality (³10 years) between EVAR and OSR were reported [12].

The ESVS guidelines for the management of elective AAA [1] recommend EVAR as the first option in patients with reasonable life expectancy and OSR for patients with long life expectancy (>15 years).

Elderly patients in good general condition and with age being the only significant risk factor for surgery should be treated with EVAR provided there is a favourable anatomy and an acceptance of the appropriate follow-up programme.

Controversy was fuelled by the NICE guidelines [13] based on evidence from RCT and cost-effectiveness assessment recommending OSR as the first option for intact aneurysms unless contraindicated and limiting the use of EVAR for hostile abdomens or high-risk patients. Criticism emerged as cost analysis was based on surveillance programmes using CTA, when more rational, less costly and equally effective strategies based on evaluation of sac stability and growth could be adopted. Also, the validity of historical morbidity and mortality data from OSR in the present EVAR era was questioned, as in many institutions open repair expertise is becoming scarce [14].

Unfavourable anatomy is a key issue, as standard endovascular solutions are associated with worse long-term outcomes. Strategies to obtain better proximal and distal fixation and sealing require more liberal use of fenestrated grafts proximally, preserving the visceral and renal arteries, and IBDs distally on the external iliac artery and maintenance of functioning hypogastric arteries.

Selection is, therefore, determinant for EVAR success, from compliance to anatomic requirements, to surgical team expertise in advanced endovascular technology to accommodate more complex repairs, adherence to structured surveillance programmes and timely reinterventions to improve the long-term durability and safety of EVAR.

In conclusion, the choice of treatment in intact aneurysms must be patient-tailored: both physician and patient should be engaged in the decision process with full disclosure of the benefits and risks of both open and endovascular techniques. Centralisation and referral to high-volume centres with expertise in both OSR and EVAR must also be considered as volume and institutional experience are associated with better outcomes [1,15].

B. Ruptured aneurysms (rAAA).

AAA rupture is associated with high mortality, ranging from 18 to 50% depending on treatment strategy, centralisation of care, pre-hospital transportation, resuscitation strategies, and dedicated postoperative care. For patients with suitable anatomy, EVAR may be superior to OSR especially in those with prohibitive risk for OSR [15].

Four RCT comparing EVAR to OSR [16-19] in patients with confirmed aneurysm rupture on CT scan reported no significant differences in 30-day mortality, with a trend towards lower short-term mortality in the EVAR group.

At three years, EVAR was shown to be associated with lower mortality, 48% compared with 56% in the OSR group (HR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.36-0.90); however, at seven years, no significant differences existed between those groups (HR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.68-1.08) [20]. Reinterventions were not different between the two groups, but a better quality of life was obtained in EVAR (gain in QUALYs of 0.17, 95% CI: 0.00-0.33) at three years and also a lower cost with the endovascular strategy. Other important findings from the IMPROVE trial were: i) mortality reduction associated with longer aortic neck length and blood pressure levels - for every increase of 10 mmHg in systolic blood pressure, the survival odds increased by 13%; ii) use of local anaesthesia in EVAR increased the chances of survival fourfold; and iii) better outcomes in female and unstable patients [19].

Observational data from large registries also confirmed a 30-day mortality reduction of 13-14% in patients submitted to EVAR when compared to OSR, lower perioperative complications and shorter length of hospital stay [20].

Society guidelines have recommended EVAR as the first option for rAAA in patients with suitable anatomy [1,15]; the NICE guidelines favoured EVAR over OSR as the preferred option in patients >70 years of age and women, OSR being advised for younger men <70 years [13].

In rAAA, a pre-hospitalisation strategy to prevent massive fluid transfusion, acceptance of permissible hypotension, a fast-track system to provide CTA evaluation and rapid access to the operative room are key elements for success, along with detection of early complications such as abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) associated with colonic ischaemia and multi-organ failure [1].

Recommendations for practice

- Management of AAA should be centralised in high-volume institutions with expertise in OSR and EVAR.

- Open repair of AAA – first option for young and fit patients and connective tissue disorders, infections and post-EVAR ruptures or infected endografts.

- EVAR – first option for older and sicker patients and also for younger patients with suitable anatomy provided that lifelong surveillance programmes are implemented.

- Complex endovascular grafts with fenestrations (FEVAR) to extend the proximal area of fixation and distally with the use of IBDs for distal fixation should be used in unfavourable anatomies for standard repair.

- For AAA ruptures, a structured policy for immediate EVAR and management of ACS complications leads to lower mortality and better survival.