The rupture of aneurysms

In the last 30 years, the epidemiology of abdominal aorta aneurysms (AAA) has changed, with a reduction in the incidence of ruptured aneurysms (rAAA). This phenomenon has its root in both the decreased habit of smoking and the increased number of elective procedures. Nonetheless, the death toll as a result of rAAA remains high [1,2]. Furthermore, the ageing of the world population will increase the number of patients with aneurysms.

A solution to the problem may be a mass screening of the population above 60-65 years of age. These programmes have been carried out only in limited geographical areas, mostly because a huge number of aneurysms would place an excessive burden on healthcare facilities.

In 1984, Denton Cooley wrote an editorial on how AAA should be approached, in which, examining the problem of screening AAA in a US population, he estimated that one million new cases could require to be dealt with by the American healthcare system, and concluded that “we do not believe that the problems of increased mortality and cost associated with rAAA are best solved by detecting all aneurysms in the adult population and resecting them” [3]. Since then, a lot of water has flowed under the bridge; however, the issue is still controversial [4].

Since the very beginning of “aneurysm science” the research efforts of clinicians and pathologists have concentrated on aneurysm formation, the so-called “dilating” atherosclerosis, as opposed to “stenosing” atherosclerosis. Aneurysm rupture was seen as an inevitable consequence of aortic/arterial dilatation. In fact, the aneurysm wall is characterised by the presence of fragmented elastin, calcifications and sclerosis of the middle layer. However, it soon became clear that not all aneurysms experience expansion and rupture. The prediction of the risk of rupture is now the primary goal of clinicians and researchers.

In 1980, in his classic experiments with collagenase and elastase, Philip Dobrin showed that, while the in vitro treatment of the arteries with elastase led to a strong dilation of the walls, only the treatment with collagenase was able to cause arterial rupture [5].

Aortic compliance is an important determinant of cardiovascular function. The elastic behaviour of the aorta is mainly due to the presence of elastic lamellae in the middle layer, but other molecules, especially collagen, determine the physiological as well as the pathological evolution of aortic compliance. Elastin fragmentation, as well as calcification and sclerosis, produces an increased stiffness with age. Therefore, the measurement of aortic compliance may be of great interest to estimate aortic wall degenerative processes [6].

In 2006, a study of regional aortic compliance (in the descending thoracic aorta [DTA]) unexpectedly revealed that the population of rAAA survivors differed completely from the population of patients with non-ruptured AAA. The study was based on the detection of pulse wave velocity (PWV) which is inversely proportional to aortic compliance. While the patients operated electively showed a Gaussian trend, with a reduced compliance, typical of ageing and atherosclerosis, patients with rAAA expressed a “biphasic” trend, with a clustering in the “zone” of a low PWV, corresponding to a high, juvenile, compliance [7].

In recent years, other methods have been developed to estimate other factors such as wall stress by imaging techniques. However, they are technically complex, time-consuming and, in fact, have not found wide application. A perfect tool to use is not yet available. However, several methods of non-invasive imaging, including DTA compliance, have been reviewed as important predictive means [8].

Risk diagram and score index

The cardiologist who needs to evaluate a patient with AAA requires an algorithm that combines efficacy with simplicity and availability, and that can be performed during the same visit with an ultrasound imaging medium (fast and effective).

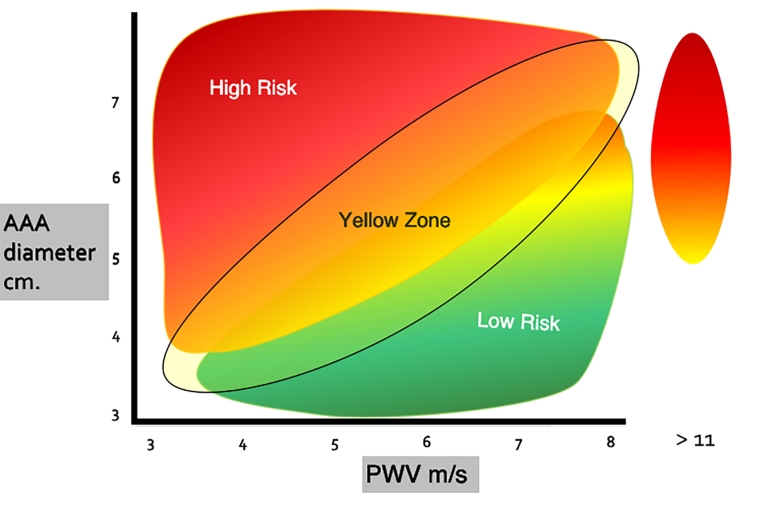

The diagram (and the index) are based on the combined application of the diameter of the AAA and the PWV in the tract of the descending thoracic aorta. In practice, the largest diameter (>55 mm) associated with a low PWV (high compliance) identifies the high-risk area (red, Figure 1). On the other hand, a smaller diameter when associated with a PWV 6-9 m/sec identifies a moderate risk (green, Figure 1). Between the two, a third area is identified, called the yellow zone, which corresponds to an area where the risk is not well defined, and which provides closer control of the patient.

Figure 1. AAA risk of rupture. In the diagram AAA diameter and PWV of DTA are plotted. The high-risk zone (in red) is due to the combination of diameter (>5.5 cm) and PWV (<6 m/sec). The low-risk zone is depicted in green. A wide “yellow zone” is represented, in which the additional risk factors become determinant.

A secondary risk zone is considered for PWV values >11 m/sec.

An index can also be determined even if a clinical judgement based mainly on the diagram is preferable to a mathematical calculation at this stage. However, the index can be calculated by attributing the value of 4 to the two main risk factors (AAA diameter and PWV) and 1 to the secondary ones. A sum above 10-12 can be of further help in identifying the subjects at higher risk (Table 1).

Table 1. Factors for the evaluation of risk of rupture of AAA. AAA diameter >55 mm and PWV <6 m/sec are considered high-risk, determinant parameters. The other important factors must be considered for a final judgement after the AAA diagram.

|

Parameter

|

Risk

|

Judgement

|

|---|---|---|

| Aneurysm diameter >55 mm | very high | AAA risk diagram |

| PWV <6 m/sec | very high | |

| PWV >11 m/s | medium | Additional factors |

| COPD | medium | |

| Smoking | medium | |

| Female gender | medium | |

| Thrombus (ILT) | medium | |

| Family history | medium | |

| A. calcification | medium | |

| Diabetes | protective |

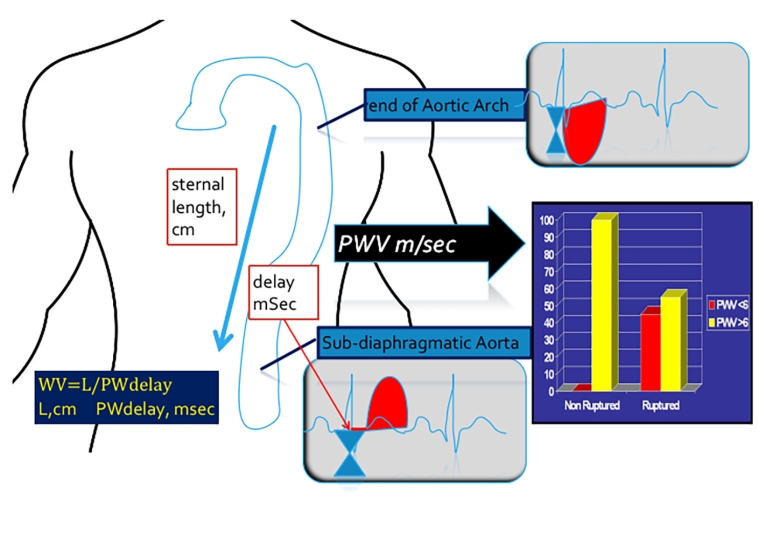

The test of PWV in DTA is realised as depicted in Figure 2 [7,9].

Figure 2. Doppler echo determination of DTAorta PWV (compliance). Doppler echocardiographic method for the evaluation of PWV in the descending thoracic aorta [9]. The bar graph shows that in the group of non-ruptured AAA no patients presented a PWV <6 m/sec [data from ref 7].

The Doppler wave is recorded at the isthmus, and then in the sub-diaphragmatic aorta. These two measurements are obtained through the suprasternal window and the subcostal window.

There is a delay between these two recordings. PWV is a velocity, space/time. The sternal length is assumed as the aortic length, in cm, and the delay is expressed in msec.

The formula is: PWV = L/PWdelay

The diameter of the aneurysm (cm) is plotted on the abscissa and the PWV (m/sec) is plotted on the ordinate (Figure 1). Other risk factors (Table 1) are considered for a better risk assessment. An additional risk area can be considered for PWV values above 11 m/sec [7]. Such a marked reduction of aortic compliance causes an increased stress on the aneurysm wall.

Conclusions

The problem of abdominal aorta aneurysm is similar to that of intracranial aneurysms and of aortic dissection. They all share a comparable behaviour, a high number of aneurysms, and a limited number of ruptures, with a high mortality in case of rupture. Furthermore, since all the surgical procedures present a low but not negligible mortality risk and a high cost for the community, a widespread and almost symptomless disease, an apparently safe condition, can become a fatal event, but in a very small percentage of cases. Therefore:

- There is an indication for a screening programme.

- It is not correct to operate all the discovered aneurysms.

- A method is needed to identify potentially fatal cases with reasonable accuracy.

- This method must be effective and simple.

We know that small aneurysms (4.0 to 5.4 cm.) have a different rupture rate than larger ones [10]. The test of PWV in DTA has good sensitivity and specificity. In addition, the diagram associating the PWV with the diameter improves the reliability of the forecast. The assessment of the minor risk factors leads to further reliability. However, the rupture of the aneurysms is a multifactorial event, a combination of biochemical and haemodynamic factors, congenital and acquired, and an estimate of the risk of rupture still implies a certain margin of error.

In conclusion, the association of the PWV of the DTA leads to a significant improvement in the simple and classic measurement of the aneurysmal diameter.

The proposed risk diagram can be a ready to use instrument for the cardiologist, since both aneurysm diameter and DTA compliance can be carried out in a single session, in a few minutes, in most cases. It is suggested as a new improved version of the already used (and effective) diameter and can serve as both an affordable clinical method and a research tool.

In fact, the integration of the diagram with the other risk factors described in Table 1 can be implemented on a simple basis, allowing a better clinical evaluation of the risk, as well as adopting it as an index.

More basic research on DT aortic compliance, i.e., studying its molecular correlate, would probably shed more light on specific molecules responsible for rupture. In the present state of knowledge, collagen is the most important suspect.