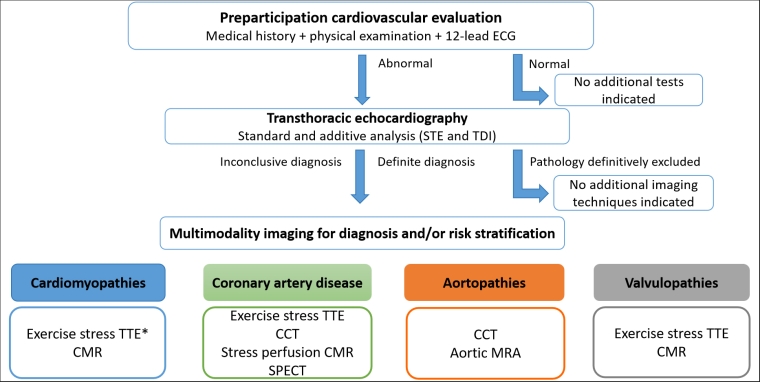

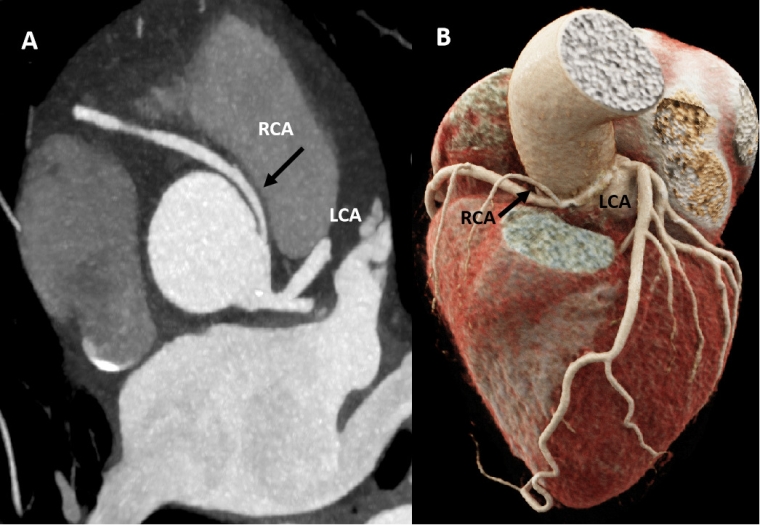

Aortopathy

Vigorous ET increases parietal tension in the aorta, which can result in remodelling. Previous meta-analyses in athletes <35 years of age have shown slightly greater aortic root diameters compared with sedentary controls. However, the aortic diameters in young athletes rarely exceed >40 mm in men and >34 mm in women. In professional athletes, recent studies suggest a higher prevalence of aortic dilation (21% >40 mm) as compared to age- and sex-matched sedentary controls with an equivalent cardiovascular risk factor burden. Nevertheless, it is unknown whether this mild dilation confers a greater risk of an aortic event [22].

Once a dilated aorta is documented, the risk of rupture should be assessed individually. It should be taken into account that hereditary thoracic aortic disease (HTAD) – Marfan syndrome being the most frequent – bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), a positive family history of dissection or SCD, high blood pressure and larger aortic diameters and strenuous strength exercise confer greater risk [1,23].

Thoracic aortic dilatation is generally asymptomatic and may go unnoticed on physical examination and/or on the ECG. It may debut as an acute aortic syndrome, which is a rare, but is a confirmed cause of SCD in athletes [1]. Imaging techniques therefore become essential in this clinical scenario.

TTE is the most routinely used imaging technique for diagnosis and follow-up. It provides a correct measurement of the aortic root and the proximal ascending aorta, assessing the presence of pathological flows in the aortic arch and, on the other hand, the functionality of the aortic valve [17]. Its main disadvantage is not being able to fully assess the aorta [17].

A global baseline assessment of the aorta, a precise measurement of the maximum diameter, location of the aneurysmal segment and characteristics of its wall can be done with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). MRI is generally preferred over CT because of the risk of cumulative radiation exposure; this is especially true for young people who need serial follow-up [23,24]. CT angiography should be considered in case of MRI contraindication and/or prior planning of a surgical or percutaneous intervention.

All patients with an HTAD should undergo at least yearly imaging of the ascending aorta with TTE or MRI, depending on the case. In athletes with BAV or tricuspid valve (TAV) and a non-dilated aorta (<40 mm), follow-up every 2-3 years with TTE is recommended [1,24]. In athletes with BAV or TAV with diameters between 40-45 mm, the frequency of TTE may be either every 1 or 2 years depending on rate of growth [23]. An MRI may also be considered as part of the initial study or in case of discordant measurements by TTE. For patients with an aortic diameter ≥45 mm, a baseline MRI is recommended, along with annual TTE or even more frequently in cases of accelerated growth [24].

Valvulopathy

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV)

BAV is the most prevalent genetic valve disease both in the general population and in athletes (0.5-2.0%). Although still controversial, the available evidence suggests that the progression of BAV occurs independently of sports practice [25,26].

Athletes with BAV may present stenosis or insufficiency and its management is similar to that of tricuspid valve disease [1]. When the valvular dysfunction is mild or absent, BAV may go unnoticed during physical examination. ETT is the first-line technique, allowing for an evaluation of the valve morphology and for the presence of potentially associated coronary anomalies to be ruled out [27].

On the other hand, BAV is associated with a small, but increased risk for ascending aortic aneurysm or dissection, and therefore with SCD. As for BAV-associated valvular dysfunction, the impact of ET in aortic dilation is unclear. A single study comparing elite athletes with BAV, non-athletes with BAV and athletes with TAV showed no impact of athletic status on the aortic growth rate. However, studies with larger populations and longer follow-ups are needed to confirm this statement. ETT is again the first-line imaging technique for this scenario, as it allows the evaluation or aortic diameters and to discard BAV-associated aortic coarctation [2]. Aortic MRI and CT complement aortopathy evaluation- as described in the previous section.

Aortic stenosis

Aortic stenosis is a well-known cause of exercise-related sudden cardiac death, but is responsible for fewer than 4% of events in young athletes [1]. Decreased exercise tolerance, dyspnoea on exertion, or exercise-induced angina in an athlete with a systolic murmur should make us suspect this valvular disease.

The most common aetiology in the elderly population is degenerative, but in young individuals, the presence of an underlying congenital pathology such as BAV must be ruled out [28]. Echocardiography is the first-line technique for its diagnosis. It provides quantification of the stenosis severity, ventricular function and myocardial thickness as well as an evaluation of the underlying mechanism of the stenosis.

In individuals affected by moderate aortic stenosis who are asymptomatic and have a normal haemodynamic response, the evaluation of the aortic mean gradient during exercise by exercise echocardiography has an additional prognostic role; an increase of more than 20 mmHg is independently associated with a higher risk of adverse events during follow-up [29].

On the other hand, in special cases, in which the information from the TTE is inconclusive or additional information is needed for an accurate diagnosis or to decide the best therapeutic strategy, non-invasive multimodal imaging can help us. The use of CCT is especially useful, as it is the complementary technique of choice to assess valve anatomy and calcification and to evaluate the characteristics of the annulus, aortic root, entire aorta and the aortoiliac vascular axis, allowing, as well, for the evaluation of the coronary arteries, especially in patients with a low probability of coronary artery disease [30].

Finally, CMR provides tissue characterisation identifying myocardial fibrosis and has also a promising role in the detection of subclinical cardiomyopathy through the use of myocardial T1 mapping and extracellular volume quantification in those patients who have not yet developed macroscopic fibrosis. All these parameters have prognostic implications and are promising tools for determining the optimal time to treat an asymptomatic patient with preserved ventricular systolic function and severe aortic stenosis [30].

For asymptomatic individuals with a mild aortic stenosis in which the ejection fraction is preserved, the haemodynamic response to exercise is normal, and who have no arrhythmias, these individuals can compete in all sports and participate in intense aerobic and strength training if it is their desire. Individuals with moderate aortic stenosis can perform low-to-moderate intensity exercise while those with severe stenosis should be restricted to low-intensity exercise and skill sports (golf, table tennis, etc.) [1].

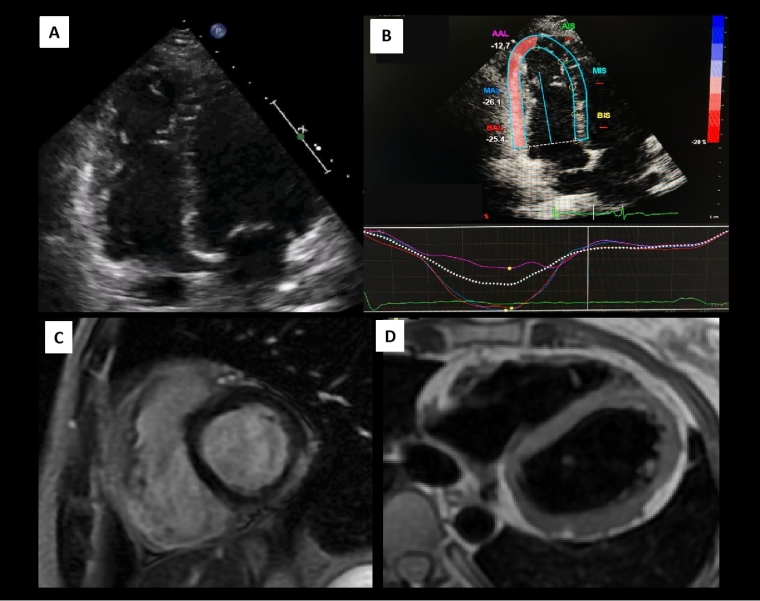

Mitral valve prolapse

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a common valvular disease in the general population (1.0-3.0%). It is caused by a myxomatous thickening of the leaflets. Diagnosis is made by TTE in which displacement >2 mm of one or both leaflets beyond the annular plane within the atrium in late systole is found [1]. In addition, TTE can help monitor the progression of mitral insufficiency, its volumetric and structural impact on the LV, and the development of pulmonary hypertension [1]. In cases in which there is doubt in grading the severity and/or in which symptoms are discordant, ESE is especially useful since it allows us to see the changes in regurgitant flow and pulmonary systolic pressure at maximum effort [30].

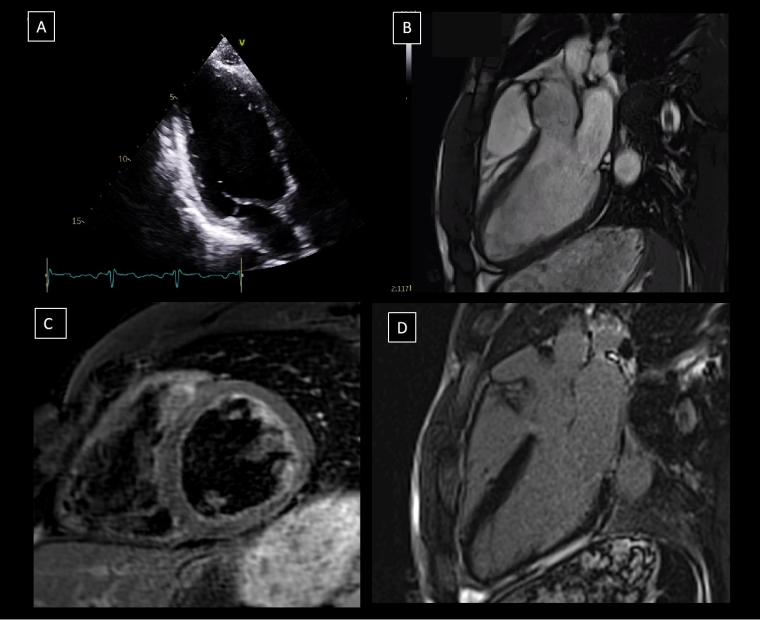

Generally, athletes with MVP have an excellent long-term prognosis. However, although uncommon, a malignant phenotype associated with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias (VA) [31,32] has been identified. Recent studies using TTE and CMR have found morphological characteristics associated with this phenotype, regardless of MR severity or LV remodelling. These include bileaflet prolapse, mitral annular disjunction and superior displacement of papillary muscles (PM) [31,32].

It is believed that these alterations generate mechanical tension in the inferolateral myocardial wall and in the PM, which can cause mechanical dispersion (double peak strain in STE by TTE) and replacement myocardial fibrosis (demonstrated by LGE-CMR) which may be a possible mechanism for a life-threatening VA [31,32].

Likewise, in athletes with MVP the initial evaluation should include a comprehensive TTE, maximal exercise test and 24-hour ECG monitoring. If any VA, morphological risk feature and/or T-wave inversion on the ECG is identified, CMR is recommended to complete an SCD risk assessment [1].