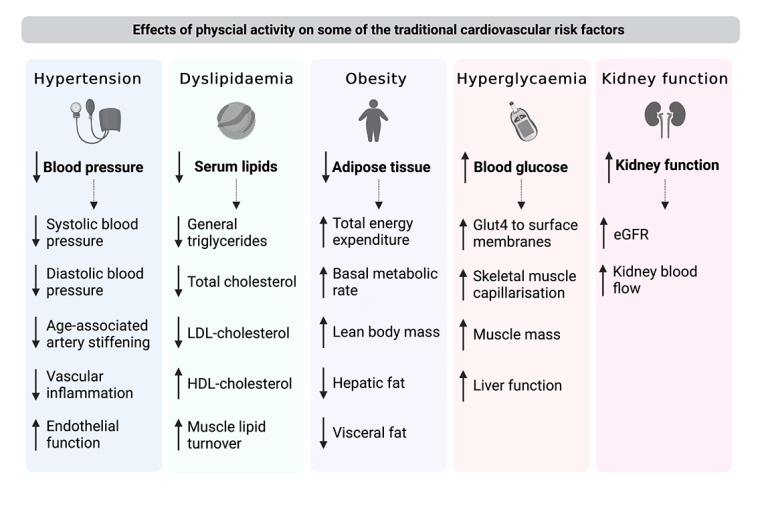

Hypertension

PA can lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure with a mean of 7 mmHg and 5 mmHg, respectively [14]. PA decreases age-associated stiffening of large elastic arteries and reduces inflammation, which collectively contribute to a decrease in blood pressure. The blood pressure-lowering effects of PA seem comparable to those of commonly used antihypertensive medications. Increasing intensity and duration of PA can reduce the need for medication [15].

Dyslipidaemia

PA provides benefits regarding the blood lipid profiles. PA increases the metabolization of fat instead of glycogen with the activation of multiple enzymes that are required for lipid metabolism in the skeletal muscles [16]. PA therefore results in an increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels by 5%-10%, and a decrease in general triglycerides by 50%, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol by 5% and, therefore, total cholesterol.

Obesity

PA reduces obesity and weight by increasing the daily energy expenditure, decreasing fat mass, maintaining a basal metabolic rate and lean body mass. PA increases psychosocial well-being, making it easier to adhere to PA routines. Aerobic exercise training in adults who are overweight or obese demonstrates a significant reduction in visceral and hepatic fat.

Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia

Individuals engaging in PA can effectively reduce their blood glucose levels. There are several mechanisms contributing to this, including the movement of GLUT4 to the surface membranes and an increase of skeletal muscle capillarisation, both induced by exercise and resulting in skeletal muscle glucose uptake and transport [17]. Insulin resistant individuals as well as prediabetes patients can increase their glycaemic control and insulin sensitivity by undertaking PA.

Coronary artery disease

Almost all individuals at low risk for exercise-related adverse events who are diagnosed with chronic CAD are eligible to engage in some form of sport, whether competitive or recreational. Some of the high-risk phenotypes for exercise-induced adverse events for patients with chronic CAD include: critical coronary stenosis >70% in a major epicardial artery, a left ventricular ejection fraction of <50% and myocardial ischaemia on exercise testing [18]. For patients with CAD who are at high risk of exercise-induced adverse cardiac events, such as acute coronary syndromes or (supra) ventricular tachycardia, competitive sports are contraindicated.

Heart failure

Exercise programs for patients with heart failure (HF) can improve exercise tolerance and quality of life and have a modest impact on all-cause mortality, HF-specific mortality, all-cause hospitalisation, and HF-specific hospitalisation [19]. Exercise training, without any restrictions, is recommended for stable HF patients who are on optimal medical therapy, patients with low NT-pro-BNP and low New York Heart Association scores. For high-risk HF patients, individually tailored sports advice is warranted.

Valvular heart disease

The combination of a large stroke volume, vigorous contractions, and an increased chronotropic state (heart rate) induced by exercise could potentially lead to an increase in valve dysfunction and to higher afterload due to blood pressure increase. Nonetheless, asymptomatic individuals with mild to moderate valvular heart disease are encouraged to engage in all types of PA.

It is important to assess both the risk of exercise-induced cardiac events based on symptoms and the severity of valve dysfunction before initiating exercise because, PA could potentially lead to larger left ventricular dimensions and therefore to an earlier need for surgery. After careful assessment and consultation, asymptomatic patients with severe aortic valve regurgitation or moderate/severe aortic stenosis may be considered for participation in competitive sports.

Aortic disease

PA is advised in all patients with an aortic pathology, even when the aorta is dilated. However, due to the increase in blood pressure and wall stress caused by intense exercise and sports, some activities can potentially lead to further aortic enlargement leading to an increased risk of acute aortic dissection. In individuals at low risk, all types of sports are allowed and safe. However, as the aneurysm-related hazard for acute aortic events increases (larger diameter, hereditary pathology, rapid growth, or hypertension) more sports (especially the more intensive ones) become contraindicated [20].

Myocardial disease

PA during active myocarditis and pericarditis is contraindicated. Individuals with cardiomyopathy or a history of resolved myocarditis or pericarditis who desire to engage in regular sports activities should undergo a thorough evaluation. This evaluation should include not only an echocardiogram and MRI, but also an exercise test to assess the potential risk of exercise-induced arrhythmias. For individuals who are genotype positive but phenotype negative or have a mild cardiomyopathy phenotype, and who show no symptoms or risk factors, participation in competitive sports can be considered, depending on potential gene-specific interaction with sports (e.g. PKP2).

Arrhythmogenic conditions

The management of sports participation in patients with arrhythmogenic conditions is based on three principles [7]:

(1) prevention of life-threatening arrhythmias during exercise,

(2) management of symptoms to enable sports participation, and

(3) evaluating the progression of the arrhythmogenic condition due to sports involvement. In every patient, these three questions need to be addressed. PA is effective in the prevention of atrial fibrillation (AF). In individuals without structural heart disease and in individuals with well-tolerated AF, participation in sports can be considered.

Congenital heart disease

Due to the considerable variation in haemodynamic conditions and prognosis in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD), a personalised exercise plan should be established, including regular re-evaluations. However, participation in some form of PA is recommended for all patients with CHD [21]. Engaging in moderate-intensity aerobic exercise for a minimum of 30 minutes, 4 to 5 times a week, is considered both safe and effective in almost all patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) [22].

Risk stratification and safety

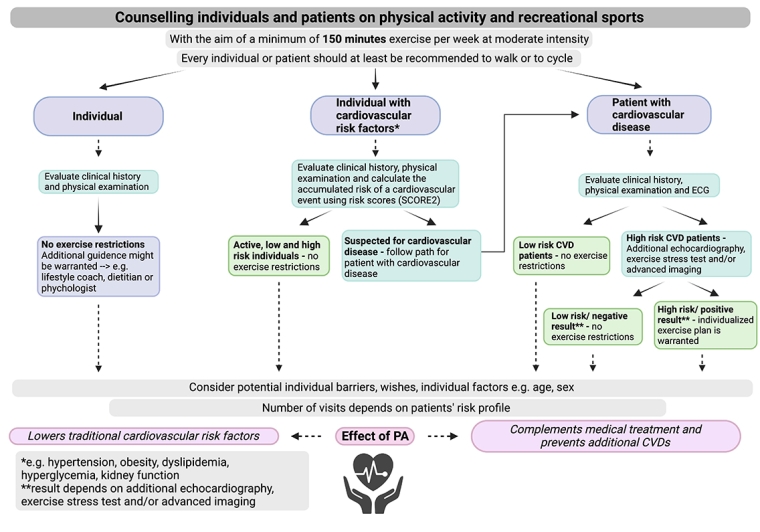

General population

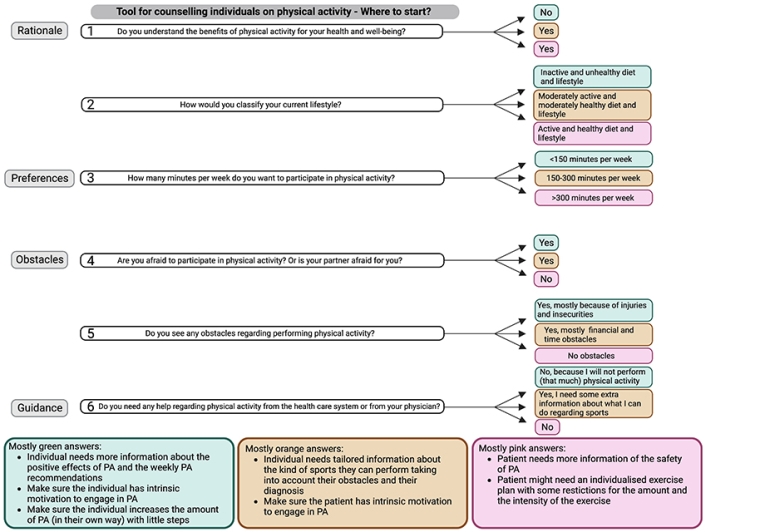

Encouraging individuals in the general population to perform PA and adopt a healthy lifestyle is important to prevent (cardiovascular) risk factors and associated disease and mortality. An evaluation of an individual’s clinical history and a physical examination by a general practitioner can help to identify the type of sports a patient can or cannot engage in. For example, if you have an individual with severe rheumatoid arthritis in the knees, it might be more appropriate to choose swimming, walking, or biking. To counsel individuals effectively, it is important to draw a distinction between those who are already active and those who are sedentary. A sedentary individual might need more help and a slower PA built-up scheme compared to an individual who is already active. Lifestyle coaches, dietitians and psychologists can provide extra guidance for patients who struggle to adopt a healthier lifestyle.

Individuals with cardiovascular risk factors

Following current recommendations [7], calculating the accumulated risk through cardiovascular risk scores (e.g., SCORE2), evaluating the patient’s clinical history and performing a physical examination for cardiovascular events in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors determines the safety of PA and permitted exercise intensity. Individuals with a low determined risk do not require any exercise restrictions.

Patients with cardiovascular disease

Since all exercise yields a positive effect on cardiovascular health, some forms of exercise should be recommended to all patients. Risk assessment should at least include a thorough physical examination including electrocardiography while also taking a patient’s complete clinical history into account. Depending on the screening results, low-risk patients with CVD (low-risk CAD, stable HF, asymptomatic/mild valvular heart disease, low risk aortic disease, well-tolerated AF, simple CHD) require no exercise restrictions [7]. Additional risk assessment is required for high-risk patients prior to PA and should at least include echocardiography, an exercise stress test and, when needed, advanced imaging. Screening before participation in recreational and competitive sports is mostly focused on detecting disorders potentially associated with sudden cardiac death. For high-risk patients with CVD, an individualised exercise plan is warranted. Following the 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with CVD, high-risk patients should receive counselling more frequently than low-risk patients [7].

Exercise may complement the need for medication and contribute to a reduction in polypharmacy. In addition to the simplification of the management and the reduction in healthcare costs, this could be a motivation to increase PA levels by engaging in relatively simple PA such as walking or cycling, people can easily meet the recommended activity levels throughout the week.