Keywords

ACTIVE principles; person-centred care; psycho-cardio team; stepped-care model

Abbreviations

CBT: cognitive-behavioural therapy

CV: cardiovascular

CVD: cardiovascular disease

SMI: severe mental illness

Take-home messages

- Integrate care: Form a multidisciplinary psycho-cardio team to integrate mental health as a core component while delivering person-centred optimal CV care.

- Screen systematically: The ACTIVE principles provide applicable instructions to implement routine, systematic mental health screening using validated two-item tools (PHQ-2, GAD-2) following acute events and periodically during follow-up.

- Prioritise behavioural therapy: The basis of treatment is a stepped care approach that utilises effective psychological interventions like cognitive-behavioural therapy (improving both psychological and potentially clinical CV outcomes) and behavioural activation (improving QoL in heart failure/depression).

- Manage severe mental illness (SMI) cautiously: The management of SMI requires intensive, coordinated effort, cautious prescription of psychotropic drugs due to their CV side effects (e.g., QTc prolongation), and mandatory monitoring and compliance support.

Introduction

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) mandates rigorous and transparent procedures for developing its clinical consensus statements (CCS), which serve as crucial tools that enable healthcare professionals to synthesise complex clinical evidence and implement optimal diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. While these documents articulate the official position of the ESC, they explicitly affirm that they do not supersede the treating clinician’s individual duties, specifically regarding appropriate clinical judgment, adherence to professional ethical standards, and verification of country-specific regulations for medications and devices. The rigorous development process begins with the selection of a diverse task force comprising practitioners, methodologists, and patient representatives selected via open call, ensuring broad regional inclusion. Consensus on the final management statements is achieved through a modified Delphi approach, requiring a high threshold of greater than 75% agreement. To guarantee ethical integrity, funding is strictly internal to the ESC, completely prohibiting healthcare industry involvement, and all declarations of interest are meticulously reviewed and published. The CCS content refers to biological sex and evidence-based medication use, though the final ethical and regulatory decision to prescribe these remains the sole responsibility of the treating clinician. This comprehensive process is further secured by continuous supervision from the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee and subsequent multiple rounds of double-blind peer review [1].

The consensus statement

This consensus document, underscoring the significance of integrating mental health into cardiovascular (CV) care, was collaboratively produced by a multidisciplinary task force, spanning specialists such as cardiologists, psychiatrists, and individuals with lived experience, operating under the guidance of the ESC clinical practice guidelines committee. Tackling the scarcity of evidence to direct clinical actions, the task force strategically employed a modified Delphi process. This methodology facilitated the generation and ranking of 34 specific management consensus statements, which encompass practical suggestions for healthcare professionals, based on the scoring done using a Likert ordinal scale [2].

Crucial relationship between CV and mental health and disease

Mental health is fundamentally defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a complete state of well-being, enabling individuals to effectively navigate life's stresses, realise their capabilities, function efficiently through work and learning, and contribute meaningfully to their communities. In contrast, mental health conditions represent a clinically significant disruption in an individual's cognition, emotional regulation, or behaviour, often resulting in substantial distress or functional impairment in critical life areas [3]. Importantly, this analysis intentionally spans the entire continuum of mental states, ranging from optimal positive mental health features to experiences of severe mental stress [1].

Tackling problems

Despite the robust relationship between mental well-being and CV health, existing clinical practice faces significant challenges. Insufficient professional awareness of mental health prevalence and its profound impact on cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, quality of life (QoL), and prognosis persists [4]. Furthermore, routine CV care systematically fails to integrate appropriate screening, evaluation, and management of these crucial psychological factors [5]. Addressing this requires acknowledging the needs of family and caregivers, as both conditions affect the wider social network [1, 6]. Consequently, mental health must shift from an auxiliary concern to a primary goal within CV care models, necessitating greater professional knowledge and the implementation of person-centred care [7]. To ensure comprehensive support and specialised guidance for people with CVD and their caregivers, it is essential that the multidisciplinary team incorporate a collaborating mental health professional, forming what is termed the psycho-cardio team [1].

The psycho-cardio team

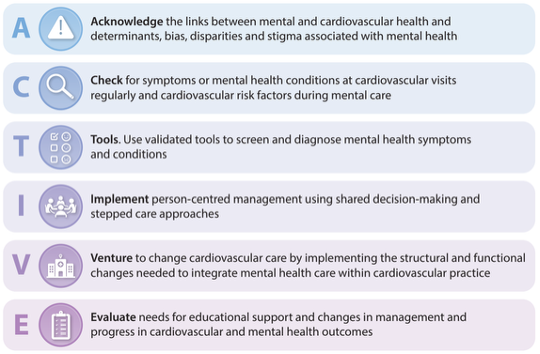

Patients with both cardiovascular disease and mental health concerns should be receiving integrated, person-centred care from a specialised group known as the psycho-cardio team. It is an intentionally formed team comprising multiple specialists, such as nurses, doctors, psychiatrists, and psychologists, all working together to benefit patients [8]. The structure of the team should ensure comprehensive care aimed at improving mental health in people with CVD. For this approach to be successful, the team should use the ACTIVE principle. This principle encompasses six components ranging from urging everyone to Acknowledge the strong connection between CVD and mental health, to healthcare providers (like doctors or nurses) Checking regularly on the patient’s emotional well-being during visits. It is critical that Tools, such as checklists or questionnaires, are used to assess the psychological status of the patient, and for the care provider to feel comfortable asking their team members to use them if they haven't already. Once the care provider’s status is clear, the team can Implement changes through shared decisions and a stepped approach. Since combined mental and CV care is often not received, patients should Venture forward and collaborate on changing the system to make this care happen. Finally, the process concludes when the team Evaluates the changes to ensure that the mental health care is actually improving the condition of the patient [1] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The ACTIVE principles to improve mental health in CV care. Reproduced with permission from [1].

CV services are encouraged to strategically implement this team approach, scaling efforts based on local population and available resources. The practical adoption of the ACTIVE principles serves as an effective mechanism for transforming routine care toward integrating necessary mental health services [1].

Integrated care framework

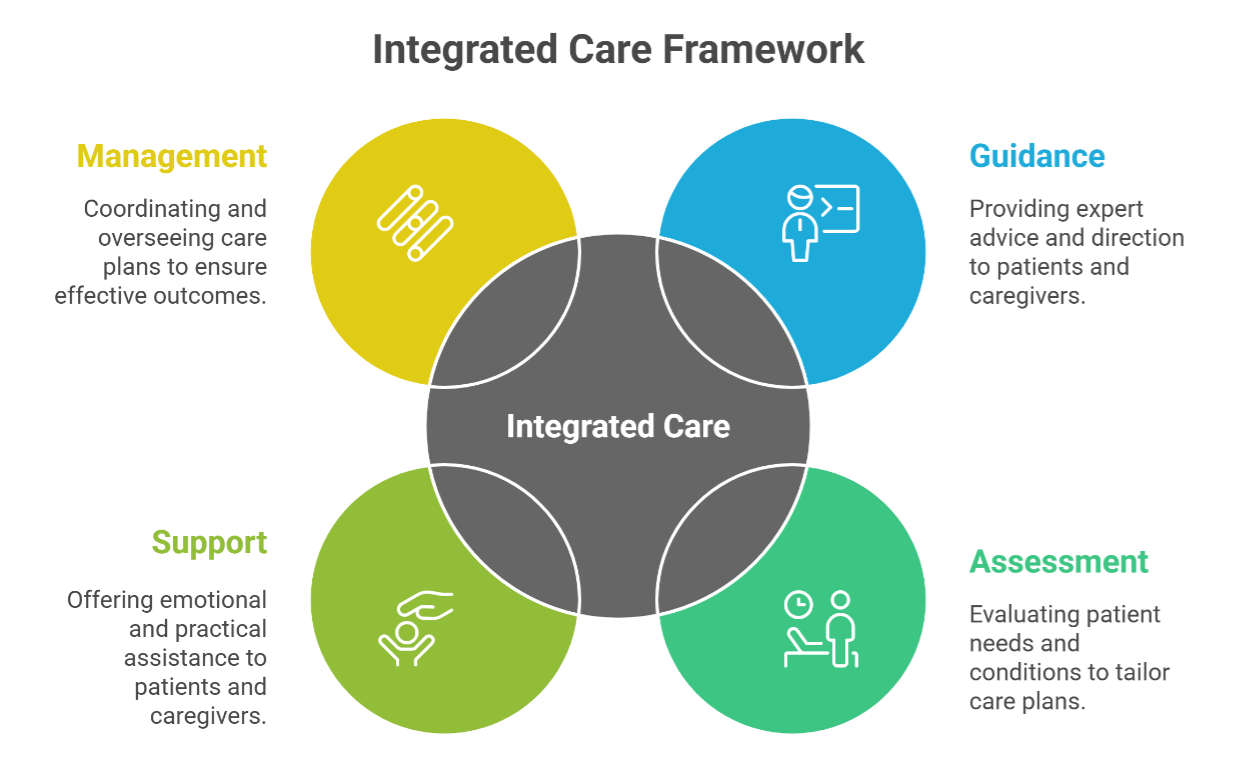

Figure 2. The psycho-cardio team works with patients and their caregivers to provide integrated care.

Caregiver support

The relationship between mental health and CV risk is profound; positive psychological indicators, such as optimism and high life satisfaction, correlate with reduced CV risk [9, 10]. Conversely, various hazardous psychosocial elements, including social isolation and financial pressures, alongside formal mental health diagnoses like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), markedly elevate the likelihood of developing CVD. Given this critical association, consensus mandates the integration of screening for depression, anxiety, and PTSD into standard CV risk assessments. Furthermore, healthcare providers and caregivers bear the responsibility of recognising these risks, informing patients, and advocating for system-level improvements [1] (Figure 2).

The interplay between CVD and mental health conditions, notably depression, anxiety, and PTSD, is multidirectional, increasing mutual risk. Depression significantly impedes self-management and treatment adherence in CVD patients, worsening prognoses. However, the influence of anxiety and PTSD on CV outcomes remains less certain [11-13]. Interestingly, caregiver support plays a pivotal role in promoting lasting lifestyle changes and enhancing patient adherence; therefore, maintaining caregiver well-being benefits both the patient and the supporter [7].

Management consensus dictates robust screening for depression, anxiety, PTSD, chronic stress, and loneliness in individuals with established CVD, requiring timely specialist referrals for positive outcomes. Further protocols mandate assessing and supporting informal caregiver well-being [1].

Patient education (explore, understand, and execute)

When the patients are tackling chronic health issues like CVD, understanding how to access comprehensive care is necessary. The task force has edited a brochure for patients on accessing comprehensive care, which includes an assessment of mental states, daily habits, and the need for supportive therapies. It is crucial that the patient and medical team are cognisant of the following:

Importance of mental health screening

If the patient is coping with CVD, feelings of fear, worry, or sadness might initially seem like a normal part of the process. However, if these feelings intensify or persist for an extended period, they can become a serious issue. Therefore, the medical team is encouraged to monitor emotional well-being regularly. If the team fails or forgets to evaluate the patient’s psychological status, using specific tools, like checklists or questionnaires, the patient should feel empowered to ask them to do so. Screening is often as simple as answering a few questions to determine how the patient feels, and it is important for overall health [14].

Lifestyle interventions

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is beneficial for both heart and mental health. The patient should focus on key measures like getting regular physical activity, practicing stress management techniques (such as yoga), eating a balanced diet, and getting sufficient sleep. It is also essential for the patient to avoid excessive alcohol use and quit smoking. Managing SMI actually makes it easier to keep up these heart-healthy habits. A dedicated psycho-cardio team is in charge of helping the patient make these changes [15].

Psychological interventions

Additionally , psychological therapies are available to improve the patient’s state of mind and behaviour. The following methods are considered effective:

- Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is a talking therapy that enables patients to actively change negative thoughts.

- Psycho-education teaches patients to learn about their emotions and brain function to help them cope better.

- Mindfulness-based techniques teach patients to feel calm and grounded by focusing on the present moment. They can also benefit from relaxation, emotional support, and social prescribing, where professionals connect them to community groups like gardening or walking clubs. However, a combination of these psychological approaches and necessary medications may be required to provide them with optimal care [16].

The stepped care model for assessment and management of mental health in CV patients

Addressing individuals with CVD requires tailored, empathetic communication, utilising active listening to understand their difficulties and family worries. Achieving quality communication is essential for open dialogue suited to cultural preferences. Furthermore, factors such as health literacy, mental health issues, and professional time constraints impact the quality of communication [1].

Identification and screening

The development of robust behavioural screening protocols, influenced by the psycho-cardio team, is essential for identifying need and directing referrals in patients with CVD. Screening procedures should be implemented following a new CVD diagnosis or an acute CV event, and also periodically during follow-up or whenever clinical indications arise. The process dictates the use of reliable, valid, and short screening instruments suitable for the setting, administered by an appropriately qualified member of the multidisciplinary team [17].

Assessment of depression and anxiety

A critical aspect of this assessment involves evaluating depression and anxiety. Specifically highlighted measures include the Whooley questions, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD)-2, and the patient health questionnaire (PHQ)-2. A positive response to the Whooley questions about diminished interest or pervasive feelings of depression or hopelessness in the preceding month necessitates immediate further evaluation for depression [12]. These established measures, including the two-item/seven-item GAD tools and the two-item/nine-item PHQ, are widely utilised due to their proven satisfactory sensitivity and specificity within the CVD patient population [17].

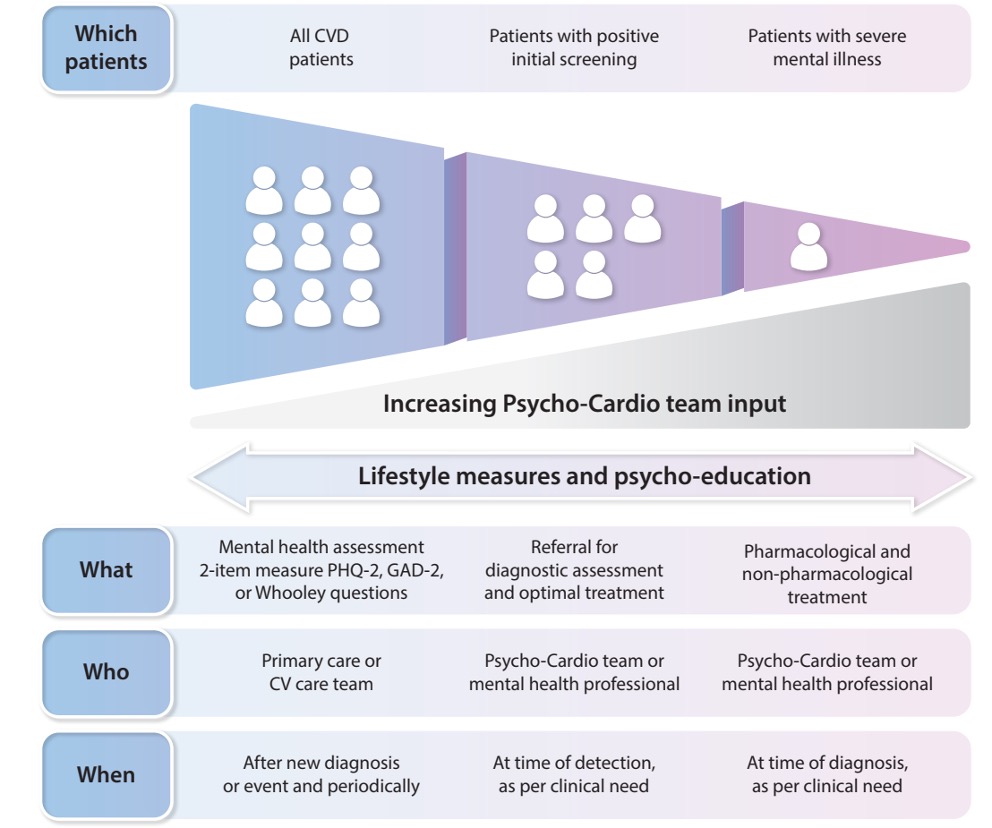

Therapeutic management

Patients with CVD showing elevated anxiety or depression scores, or those formally diagnosed with depression, anxiety disorder, or PTSD, warrant mental health intervention. Utilising a stepped care approach is suggested to encompass diverse symptom severity, resource availability, and patient preferences, allowing direct access to higher-level support when needed [18] (Figure 3).

Psychological and behavioural interventions

Psychological interventions generally result in small-to-moderate improvements in depressive symptoms, anxiety, and stress in people with coronary heart disease (CHD). For individuals living with CVD, a comprehensive suite of psychological interventions, spanning from traditional CBT to modern mobile Health solutions, are being recommended as viable therapeutic options [18].

Figure 3. Stepped care model for assessment and management of mental health conditions in people with cardiovascular disease. Reproduced with permission from [21].

CV: cardiovascular; CVD: cardiovascular disease; GAD: Generalised Anxiety Disorder; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire

Psycho-education

Psycho-education is defined as a structured intervention involving the transfer of knowledge about an illness and its treatment, integrating emotional and motivational dimensions to facilitate coping, enhance treatment adherence, and improve overall effectiveness. This approach is deemed essential across both medical and mental health disciplines, and is inherently utilised within CV care settings, notably in exercise based cardiac rehabilitation (ECR) and secondary prevention programs, where it covers disease specifics, risk factors, and recommended lifestyle adjustments. Drawing from a recent synthesis of randomised controlled trials (n=8,748), effective psycho-educational strategies must employ various modes of delivery and continue for a minimum of three months [3, 19].

Social prescribing

The fundamental principle of social prescribing is to offer personalised interventions extending beyond typical medical approaches, making use of diverse community activities like group dance or hiking. Such engagements are crucial, as they effectively combat isolation, cultivate social interactions, and significantly bolster individual mental well-being. Moreover, technology proves essential, with online platforms and mobile applications recommending suitable social prescriptions, facilitating virtual support, and allowing for progress tracking [3].

Pharmacological management

Pharmacological treatment is recommended for those with moderate-to-severe anxiety disorders and depression, as per the qualified mental health professionals.

- Antidepressants: Newer antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are generally considered safer for patients with CVD. However, SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can increase bleeding risk, particularly when used concomitantly with oral anticoagulants, requiring careful monitoring.

- Anxiolytics: The use of anxiolytics, sedatives, and hypnotics is not recommended as a first-line therapy for anxiety and depression due to the risks associated with overuse, particularly in older individuals.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM): Given the high potential for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between psychotropic and CV drugs, TDM is advised for optimisation of pharmacotherapy and minimisation of side effects [20].

Management in SMI

People with SMI face significantly increased CV risk and worse prognosis due to lifestyle factors, disparities in care, and medication side effects.

- Coordinated care and autonomy: Management should follow a person-centred approach based on the individual's "will and preference," moving away from paternalistic treatment. Interventions aimed at improving CV risk in SMI must be high intensity and highly coordinated, including both behavioural and pharmacological management.

- Risk assessment and medication choice: Routine CV risk assessment is essential, ideally before the prescription of antipsychotics and monitored periodically thereafter. Antipsychotic medications vary greatly in their propensity to induce CV risk factors like weight gain and dyslipidaemia. Special caution is required for psychotropic drugs that cause corrected QT-interval (QTc) prolongation (e.g., some antipsychotics like quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and certain antidepressants). Drugs with QTc-prolonging properties may need to be switched to newer agents with better safety profiles.

- Adherence: Promoting adherence to psychotropic drugs, potentially through long-acting injectables, is crucial as better adherence is linked to better adherence to cardiometabolic medications [20].

Addressing specific populations and situations

The consensus document systematically highlights the interplay between mental health and CVD within specific vulnerable populations, emphasising the need for a shift toward individualised and integrated care models. The analyses put forth cover sex and gender differences as well, highlighting disparities in various medical conditions, alongside specific considerations for transgender individuals. For instance, the text has explored and documented mental distress linked to cancer diagnosis and cardiotoxic treatments. The document has drawn special attention towards older adults facing multiple morbidities and frailty, underscoring the need for comprehensive geriatric assessment in this group. Furthermore, the heightened vulnerability of socioeconomically deprived populations, including migrants and refugees, due to chronic psychosocial stressors and barriers to accessing adequate healthcare, has also been analysed. The fundamental reason behind addressing these specific populations is to encourage clinicians to acknowledge these modifying factors (sex, age, socioeconomic status) when implementing treatment plans [1].

Conclusion

The high prevalence and prognostic impact of comorbid mental health conditions in patients with CVD necessitate integrated CV care. By restructuring care around the psycho-cardio team and operating according to the ACTIVE principles, healthcare professionals can implement stepped care models, prioritising lifestyle and evidence-based psychological interventions, while ensuring wise use of pharmacotherapy, within a patient-centred approach, especially in complex populations like those with SMI.

Impact on practice

Implementation of the ACTIVE principles provides a structured, actionable pathway for healthcare systems to reorganise care provision, promoting collaboration between cardiologists, psychiatrists, and allied professionals to ensure mental health is recognised and managed concomitantly for routine CV prevention and care.