Key words

congenital heart disease, Fontan, pacing, pre-procedural preparation

Abbreviations

AVB: atrioventricular block

CHD: congenital heart disease

IVC: inferior vena cava

SVC: superior vena cava

SND: sinus node disease

Take-home messages

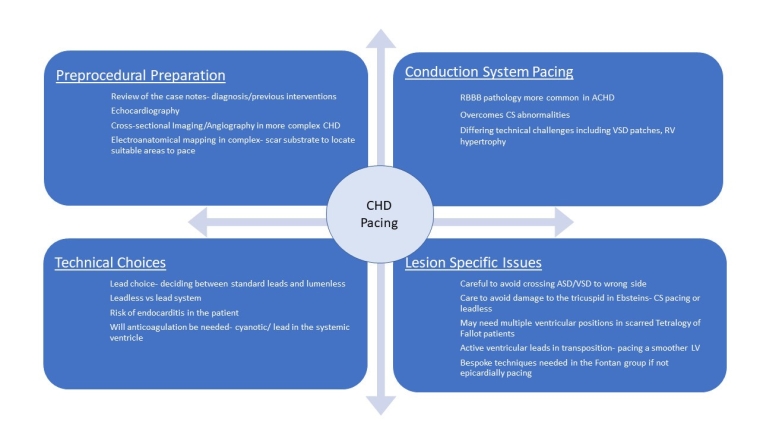

- In complex congenital heart disease periprocedural planning with a review of imaging and previous interventions is key to a successful outcome.

- Conduction system pacing is likely to become an increasingly popular choice for complex pacing in CHD.

- Interventional and hybrid techniques may become of increasing use in the most complex cohort of patients.

Patient-orientated message

When speaking to patients about pacing in CHD it is important to discuss the risks and benefits posed by pacing as well as the impact that pacing may have in terms of their long-term outlook. This includes how pacing may affect their requirement for further procedures. Many patients will have had multiple procedures throughout their life and reassuring them that techniques exist now to help them receive safe pacing is key.

Introduction

The number of patients born with congenital heart disease (CHD) per year seems to have remained largely stable [1] but despite continuing improvements in paediatric and adult care, the overall number of patients with congenital heart disease continues to rise [2]. More cardiologists are likely to see and need to treat congenital heart disease patients, many of whom have conditions where the indication for pacing is high [3]. These cases can present challenges at implantation and impose long-term considerations given the often-younger cohort who may need further structural interventions.

Indications for pacing

Most of the indications for pacing in congenital heart disease are identical to that seen in the cohort of patient’s with an acquired disease, with some nuances in more complex disease states.

Common indications are summarised below for sinus node disease (SND) and atrioventricular block (AVB) [4] in Table 1.

Table 1. Indications for pacing in CHD.

B-lines

- Cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

- Multiple, diffuse, bilateral

- Homogeneous distribution over the chest with a gravity-dependent gradient

- Usually separated or coalescent in more severe cases

- No spared areas

- Non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

- Multiple, diffuse, often bilateral

- Patchy distribution over the chest without a gravity-dependent gradient

- More often coalescent

- Spared areas

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Multiple but not necessarily diffuse or bilateral

- Usually more prevalent at the lung bases

- Usually separated or coalescent in more severe cases

- Spared areas not typical

Other LUS findings

- Pleural line

- Cardiogenic: Usually thin and regular

- Non-cardiogenic: Usually irregular and “fragmented”

- Pulmonary fibrosis: Irregular in moderate/severe cases (can appear thin in mild cases)

- Consolidations

- Cardiogenic: Usually not present unless compressive atelectasis with large pleural effusion

- Non-cardiogenic: Frequent peripheral small consolidations and larger consolidations

- Pulmonary fibrosis: Rarely present; can be seen in acute phases (i.e., alveolitis), usually of small size

- Pleural effusion

- Cardiogenic: Frequent, of variable size; anechoic (transudate), without complex appearance unless coexisting conditions; usually bilateral (often larger on the right side)

- Non-cardiogenic: Usually not large

- Pulmonary fibrosis: Rare, unless in very advanced cases or acute phases; usually not large

AVB: atrioventricular block; CHD: congenital heart disease; SND: sinus node disease

It is important for physicians to be aware of some of the more common conditions in adults with CHD that require pacing, with dextrotransposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) repaired by an atrial switch, and levotransposition of the great arteries (L-TGA) and left atrial isomerism all having high rates of pacing [5].

Periprocedural preparation

The level of periprocedural preparation is often higher than in non-congenital pacing with more workup required.

Commonly, preprocedural planning involves an echocardiogram, a review of the case notes and the interventional history but as the level of complexity increases, detailed cross-sectional imaging, angiography or 3D electroanatomical mapping may be needed.

Vascular abnormalities are much more common in patients with congenital heart disease and, if not prepared for, can cause difficulties as simple as a persistent left-sided superior vena cava (SVC) with or without a bridging vein to more complex anomalies.

As leadless pacing becomes more popular, operators will need to be more aware of complex lower limb abnormalities that may occur precluding easy inferior venous access to the heart, such as an interrupted inferior vena cava (IVC) in atrial isomerism [6]. In these cases, a superior approach from the appropriate jugular may be used.

In addition to vascular abnormalities, a childhood history of multiple interventions often leads to vascular occlusion and stenoses making access difficult and techniques utilising micropuncture or recanalisation may be needed.

Next in periprocedural preparation is to plan how to deliver the lead or leadless device which may require an understanding of obstructions such as baffles, conduits and valve replacements which are more relevant as the complexity of CHD rises. In addition to just delivering a lead to a location there can be issues as to whether the area the cardiologist can reach is paceable, such as in the Fontan circulation [7].

Equipment choices

In younger patients where there is likelihood for multiple interventions over time, the smaller lumenless SelectSecure leads (Medtronic) which are potentially easier to extract in the setting of congenital heart disease, may be a more attractive option compared to standard leads [8]. This becomes an important factor when reviewing the high rate of lead failures observed in CHD [9].

The other important equipment choice then surrounds the risk of infection and endocarditis, as despite a wide range of studies, the risk in patients with CHD is markedly higher [10]. In this context dependent on the amount and type of pacing required, leadless pacing may become a more favourable option as leadless devices have a much lower rate of infection compared to lead systems [11].

Specific issues in complex pacing in CHD

In CHD the incidence of coronary sinus abnormalities is much higher with abnormalities such as a persistent left SVC, an unroofed coronary sinus or an absent coronary sinus (CS) making traditional lead delivery difficult or impossible [12]. In these cases, sometimes Thebesian veins or collateral veins can be utilised. In some pathologies the CS may not be accessible at all for resynchronisation, such as the atrial switch for D-TGA.

In addition to this, many patients in the CHD cohort have right bundle branch block (RBBB) and the utility of resynchronisation in this cohort is less well proven than in the left bundle branch (LBB) block cohort [13].

As a result of some of these issues, conduction system pacing (CSP) has become of particular interest to doctors treating patients with CHD. There are, however, more difficulties in delivering this therapy to CHD patients that need to be thought about and overcome, which are summarised below:

- Ventricular septal defects (VSD) or a repaired VSD patch when trying to screw into the LBB area.

- Unpredictable/variable conduction system location in levotransposition of the great arteries.

- Significant right ventricular (RV)/atrial (RA) dilatation making lead delivery or support difficult.

- Hypoplastic RV with limited space to deliver leads to the conduction system.

- Severe tricuspid or pulmonary regurgitation

- RV hypertrophy preventing the lead reaching the LBB area.

- Atrial switch procedure with baffles preventing easy sheath delivery to the septum.

Although there are challenges, the superior resynchronisation opportunities and ability to deal with non-LBB block pathologies means CSP is likely to be used more frequently in the CHD cohort and can be completed in most patients with enough planning [14].

Pacing in specific CHD conditions

Atrial/ventricular septal defects (ASD/VSD)

Whilst not complex defects on their own, these can cause issues for the implant team due to the difficulty of making sure that one has not crossed into the left atrium or left ventricle inadvertently, via the defect. In these cases, careful tracking of the atrial lead into the IVC before retracting back/deployment with multiple views is helpful, as is advancing the ventricular lead into the pulmonary artery/ventricular outflow tract to confirm positioning. In addition to this, direct pressure measurement or angiography can be used to support lead positioning or a leadless device.

Ebstein’s anomaly

Depending on the severity of the disease and whether the tricuspid valve has been repaired or not, traditional pacing to the right ventricle may be difficult or not desired. In a small RV the amount of paceable myocardium maybe small and lead delivery tricky, sometimes a sheath may be required. In cases where there is a repaired or a replacement valve, traversing the valve with a lead may contribute to dysfunction or make further valve-in-valve therapy difficult. In this case either leadless pacing or a single ventricular S-1 lead via the CS may be a preferred option.

Whilst current available data suggest transvalvular leads are not associated with earlier bioprosthetic tricuspid dysfunction [15] and that valve-in-valve can be carried out with an existing lead in situ [16], many clinicians are concerned about the risk of endocarditis in leads jailed in prostheses.

Tetralogy of Fallot

The major challenge if there is no residual VSD can be in dealing with an hypertrophied RV which may have undergone multiple surgical procedures with large amounts of scar tissue and finding healthy myocardium can require multiple positions. In addition to this, the position of the heart can be relatively more horizontal in the chest and anteriorly rotated.

L-TGA

Pacing in L-TGA normally requires the use of an active lead as the subpulmonary left ventricle may have less trabeculae to deliver a passive lead to. Pacing in L-TGA can be more difficult beyond the need to use an active ventricular lead, as associated abnormalities such as dextrocardia, atrial isomerism etc. are very common and may make traditional routes or fluoroscopic views more difficult [17].

D-TGA

Again, ventricular pacing here is to a subpulmonary left ventricle and the angulation via the atrial baffle can be difficult with a lead that will bias to the left ventricle (LV) free wall or left atrial free wall. Delivery of the atrial lead almost always requires an active lead and position, again, can be difficult as the baffle may direct the lead towards the ventricle. Care must be taken also to test and ensure no phrenic capture due to the position of the leads in the LV and left atrium.

Prior to pacing in this cohort, an assessment should be made to ensure there is no baffle stenosis in the SVC baffle before the leads are placed, as prestenting a stenosis is recommended.