Lung ultrasound for monitoring decongestion in acute heart failure

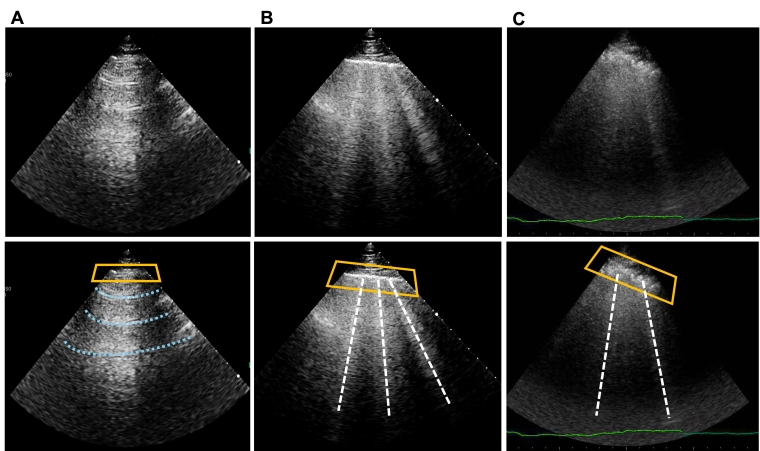

B-lines can change rapidly, as shown by their appearance during exercise [7] or real-time during lung lavage [12], as well as their decrease/disappearance during dialysis. Therefore, LUS is a useful tool for monitoring decongestion during treatment for acute HF [13].

Effective decongestion, as indicated by a reduction in the percentage or absolute number of B-lines, has also demonstrated prognostic significance. Patients with no B-lines at hospital discharge or with at least a 50% reduction in B-lines experienced fewer adverse events, such as rehospitalisation for HF, during follow-up [14, 15]. However, these findings are based on relatively small, single-centre studies.

One advantage of B-lines compared to echocardiographic parameters, particularly non-invasive haemodynamic measures like E/e' and pulmonary artery systolic pressure, is their very dynamic nature, since a significant decrease in the number of B-lines can be observed even within minutes after starting appropriate treatment.

Lung ultrasound to guide therapy in acute and chronic heart failure

Currently, robust evidence in support of LUS-guided therapy’s capacity to improve prognosis in patients with acute HF is limited [15, 16, 17]. However, some promising preliminary findings from small, single-centre studies suggest that using LUS to guide diuretic therapy in patients with acute HF may lead to improvements in outcome.

Specifically, LUS-guided treatment was linked to fewer 90-day readmissions for acute HF and longer times until readmission compared to standard care, without significant differences in safety outcomes such as acute kidney injury, hypokalaemia, or hypotension [16].

In patients with chronic HF, some randomised trials have shown that a strategy including LUS-guided treatment – mostly for diuretic therapy – can lead to a reduction in urgent visits for HF [18] and rehospitalisations for acute HF [19].

Lung ultrasound to assess prognosis

Lung ultrasound B-lines have shown to be strong prognosticators in many different settings. They predict worse outcomes, mostly in terms of rehospitalisation for HF, both if assessed at admission [5] and at discharge [4]. This is valid both in patients with HFrEF and HFpEF, irrespective of signs and symptoms of HF [5].

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines also emphasise the importance of identifying even subtle pulmonary congestion at the time of hospital discharge. This is because it's well established that patients who still have some degree of lung congestion before going home are more likely to be readmitted in the following weeks.

This prognostic value has also been demonstrated in patients with acute coronary syndromes [20], where B-lines can be a component of a "sonographic" Forrester classification: the time-velocity integral of the left ventricular outflow tract, used to non-invasively determine stroke volume, can serve as an indicator of perfusion, whereas B-lines can serve as an indicator of congestion. Table 2 provides a summary of the clinical situations in which lung ultrasound can aid in the management of patients with HF.

Table 2. Usefulness of lung ultrasound during the management of HF patients.

- Diagnosis

- In-patients:

- Rule in and rule out cardiogenic pulmonary oedema in patients with acute dyspnoea (multiple, diffuse, bilateral B-lines)

- Reduce time to correct diagnosis

- Not inferior in diagnostic accuracy compared to standard strategy (chest X-ray + NT-proBNP)

- Out-patients:

- Detect subclinical pulmonary congestion in out-patients with HF and no significant signs and symptoms

- Monitoring

- In-patients:

- Dynamic monitoring of decongestion during hospitalisation for acute HF, through reduction of B-lines

- Guiding Therapy

- Out-patients:

- Titrate HF treatment (in particular diuretic therapy) according also to the number of B-lines during follow-up in out-patients after HF admission, to reduce the number of urgent visits and rehospitalisation for acute HF

- Prognosis

- In-patients:

- Detection of subclinical pulmonary congestion at discharge to predict rehospitalisation

- Out-patients:

- Detection of subclinical pulmonary congestion during ambulatory office visits to predict rehospitalisation

Integrated cardiopulmonary ultrasound in heart failure

Lung ultrasound should be considered as part of an integrated cardiopulmonary ultrasound assessment. This would make the technique particularly powerful for cardiologists who can perform both exams together. The information gained from these two evaluations is complementary: echocardiography provides details about the underlying causes of HF, while B-lines provide information about the presence of decompensation and allow for a semi-quantification of the degree of pulmonary congestion.

We have echocardiographic data, particularly related to non-invasive haemodynamic assessment – such as E/e', pulmonary artery systolic pressure, or the severity of functional mitral and tricuspid regurgitation – that can certainly add to our understanding of the degree of decompensation. However, B-lines are typically more dynamic than these parameters. When a patient is in a compensated state, very few, if any, B-lines are visible. In contrast, echocardiographic parameters in a "compensated" patient can still be clearly abnormal, similar to what can be seen with NT-proBNP levels (the concept of "dry" NT-proBNP value).

Compared to inferior vena cava evaluation, B-lines have the advantage of representing only pulmonary oedema, whereas inferior vena cava integrates information about right atrial pressure with volemic status; this makes the simultaneous assessment of these parameters particularly informative and additive.

Lung ultrasound beyond B-lines

Lung ultrasound can be considered as a densitometer of the lung; therefore, it can assess other lung abnormalities if they are characterised by decreased air content (deaeration). An increase in air content cannot be seen at LUS; thus, a patient, i.e., with a severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease would have an LUS examination very similar to a normal subject.

- Lung ultrasound can detect pulmonary consolidations with good sensitivity, particularly when they are located near the surface of the lung. Sensitivity approaches 100% for consolidations that are in contact with the pleural line. Therefore, in a patient with dyspnoea, LUS can detect a consolidation due to pneumonia as well as a pattern of interstitial pneumonia or a pleural effusion with compression atelectasis. Some features can also help in differentiating the different types of consolidations, such as:

- Pneumonia (hypoechoic or tissue-like appearance, usually with blurred margins and visible air bronchogram).

- Obstructive atelectasis (tissue-like appearance, with well-defined margins and no air bronchogram).

- Compression atelectasis (tissue-like pulmonary parenchyma surrounded by pleural effusion in a quantity that is deemed sufficient to compress the pulmonary parenchyma); compression atelectasis is frequently seen in patients with HF and large pleural effusions and can be a predisposing condition for pulmonary superinfections.

- Pulmonary infarctions in the context of pulmonary embolism (triangular/polygonal hypoechoic peripheral consolidations with sharp margins).

- Lung ultrasound is also able to detect pneumothorax (PNX), which is characterised by an absence of lung sliding and an absence of B-lines. Rapid bedside suspicion of PNX using LUS is very valuable. Pneumothorax can not only be a cause of acute dyspnoea in outpatients but can also occur as a complication of some medical procedures, such as central venous line placement, thoracentesis, and positive pressure ventilation. Unless the patient is haemodynamically unstable, confirmation with a chest X-ray or chest CT scan is recommended.

- Pleural effusion is another important condition that can be effectively evaluated with LUS. It is frequently present in patients with HF and can provide insights into the timeline of decompensation, as pleural effusion typically develops more slowly than interstitial pulmonary oedema. The appearance of the pleural effusion can also provide information about its aetiology: HF-related effusions are usually transudates and therefore appear anechoic. Complex or corpusculated pleural effusions are often due to other conditions, which may even overlap with HF, such as cancer-related or infectious processes.

Limitations

Although it is a very useful support in the management of patients with HF, LUS should not be used in isolation to infer conclusions about a patient’s condition, except in critical situations, where the LUS findings are clear enough to confidently rule in or rule out cardiogenic pulmonary oedema with very high accuracy.

There are inherent limitations to this method because B-lines are ultimately artefacts and not direct anatomical images. Furthermore, B-lines are not a specific sign of cardiogenic pulmonary interstitial oedema, but a sonographic sign of partial deaeration of the pulmonary parenchyma and will therefore be present in cardiogenic pulmonary interstitial oedema, as well as in other conditions affecting the lung interstitium, such as non-cardiogenic oedema, pulmonary fibrosis, and interstitial pneumonia. There are some characteristics that may help to distinguish the different types of B-lines (Table 1), but still this differential diagnosis should not be done solely on LUS findings.

Assessment of B-lines and pleural effusion is mostly effective when coupled with echocardiography and, whenever possible, with venous excess ultrasound. This would allow for the concurrent evaluation in one patient of haemodynamic, pulmonary and venous congestion, which can have different behaviours and decongestive timing, also considering that signs and symptoms of HF are not only due to fluid accumulation but also to fluid redistribution.

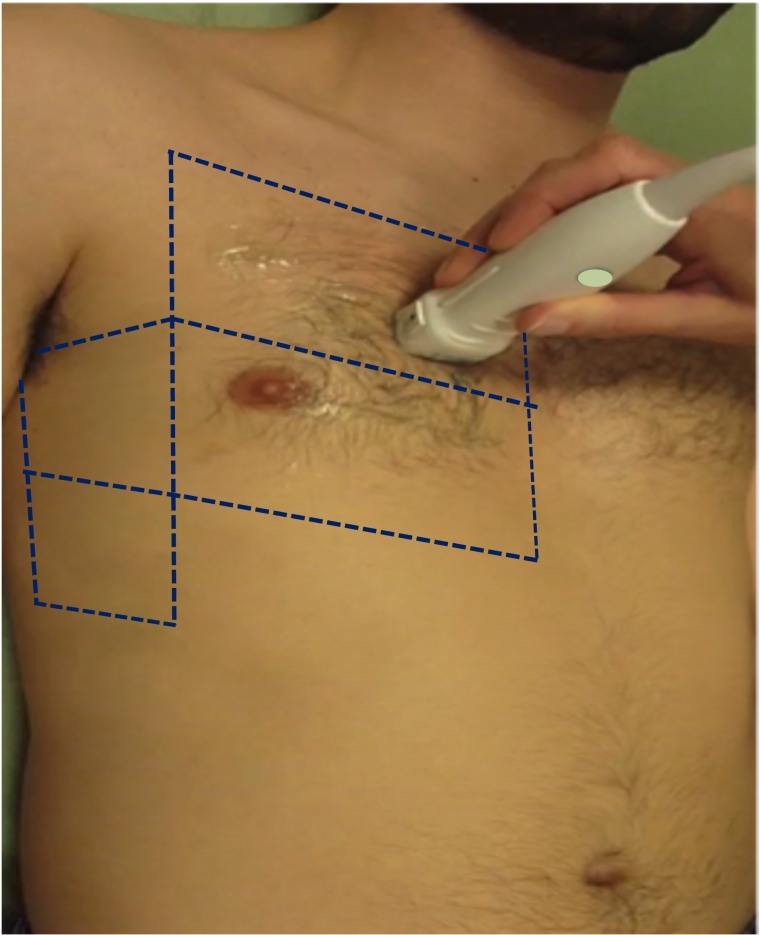

There is still some lack of standardisation in scanning schemes and quantification methods: however, the 8-zone scanning scheme is currently the most frequently used in HF, and quantification/semi-quantification is usually done with score-based or count-based methods, as highlighted above.

Intra- and inter-observer variability is another potential limitation: however, it should be emphasised that in acute patients with significant interstitial pulmonary oedema, the LUS picture will be clear and the rule in or rule out usually straightforward; on the other hand, to assess the effectiveness of decongestion we should not rely on small decreases in the number of B-lines, as such minor changes may fall within the range of inter-observer variability.

Conclusions

Lung ultrasound has entered the clinical arena in recent years, especially for the differential diagnosis of acute dyspnoea/respiratory failure.

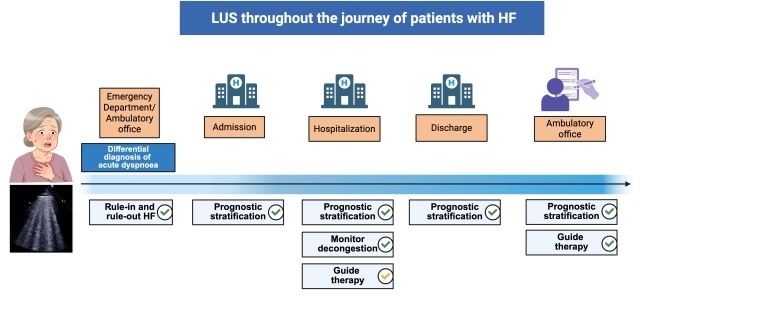

In patients with HF, LUS allows detection and quantification/semi-quantification of B-lines, the sonographic sign of pulmonary interstitial oedema. B-line assessment can support the clinician throughout the whole journey of a patient with HF, from diagnosis to decongestion monitoring, from guiding therapy to prognostic stratification.

Lung ultrasound is a relatively simple technique that yields a significant amount of information with just a brief extension of the standard cardiac ultrasound examination. When combined with cardiac ultrasound, it enables a powerful integration of clinical and ultrasound findings for a comprehensive cardiopulmonary assessment. As a point-of-care tool, it represents the quintessential "clinical" ultrasound application.