Take-home messages

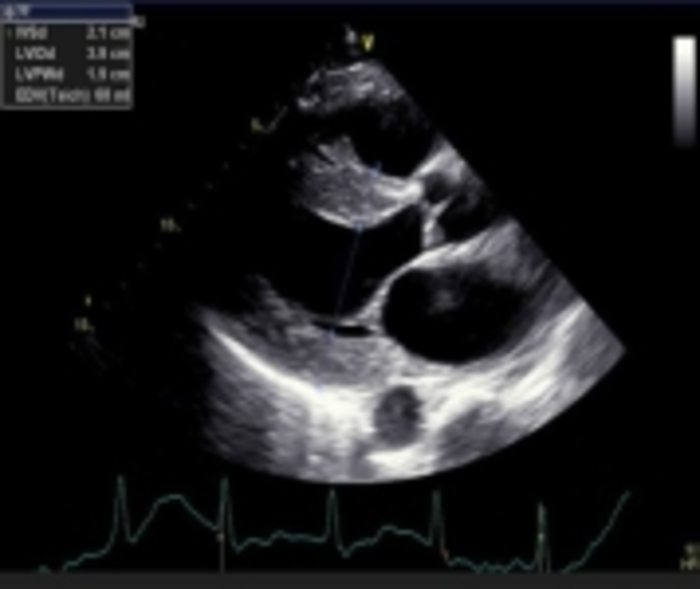

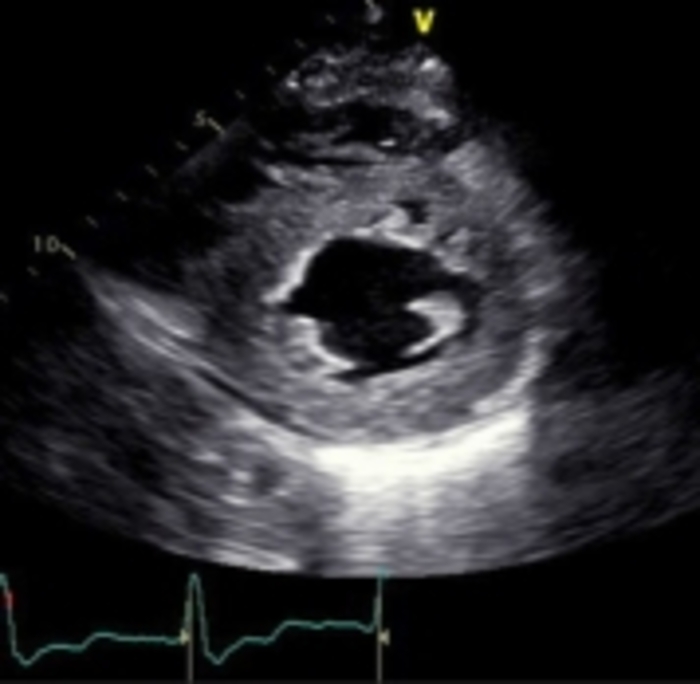

- Echo imaging that reveals LV hypertrophy may be indicative of cardiac amyloidosis (CA)

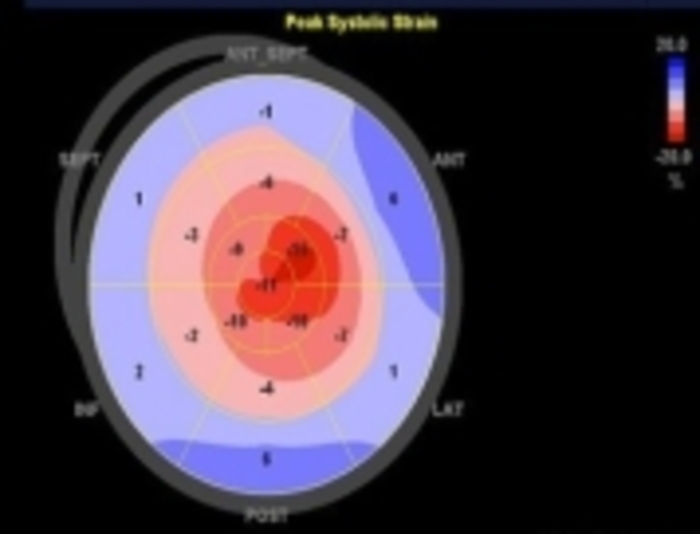

- GLS pattern of apical sparing is associated with CA

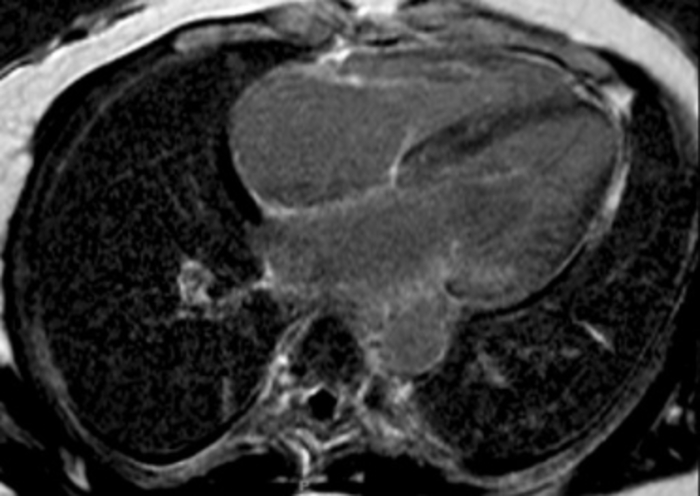

- Cardiac MRI can be very sensitive for the detection of myocardial infiltration but does not confirm the type of CA

- ECG can suggest cardiac involvement in CA but is rarely confirmatory

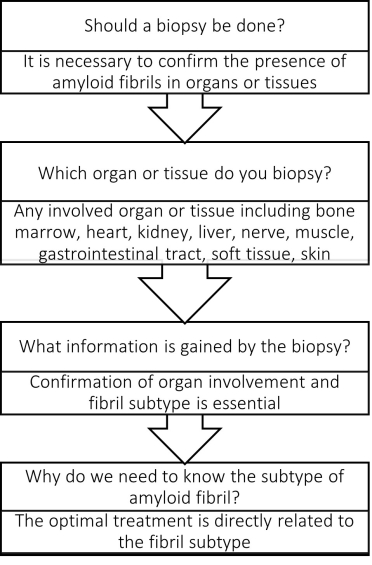

- Tissue biopsy, including myocardial biopsy, is usually necessary to establish the fibril type with CA

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a challenging multisystem condition that requires a high level of suspicion and careful evaluation of the patient history, physical examination, and available testing in order to make an early and accurate diagnosis, but also to define the extent, if any, of cardiac involvement. Depending on the manner of presentation, specific testing can effectively aid in detecting the presence of cardiac amyloidosis (CA). The multisystemic nature of this illness makes the condition difficult to treat in many situations, but certainly early identification and treatment are connected to the highest level of success [1-4]. Thankfully, many prospective clinical trials for the treatment of cardiac amyloidosis are underway and future therapies are very promising [5].

Since the presentation of this heterogeneous disease can be perplexing, cardiologists have to be aware of subtle findings and make clinical connections between seemingly disparate symptoms and signs in order to have the best overall outcome. A patient may present with any combination of cardiac, neurological, gastrointestinal, orthopaedic, or renal manifestations of amyloidosis, and typically these symptoms may be nonspecific. It has been recognised that providers may attribute symptoms to more common diseases without further investigation.

Once the identification and treatment of the amyloidosis is delayed, the benefit of targeted therapy for amyloidosis due to AL (light chain) or ATTR (transthyretin) is substantially reduced. It is important to note that a majority of educational efforts typically focus on a single organ system but the cornerstone of treatment of any form of amyloidosis, with or without CA, is a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach. The purpose of this review is to emphasise the practical opportunity for an early diagnosis of CA, keeping the multidisciplinary team approach in mind, and improving the amyloidosis-specific treatment as a result.

The landscape of treatment has changed dramatically in the last decade and guideline-type position statements are now available to provide a structure for diagnosis and treatment to clinicians [6,7]. While this is a tremendous development, the point of contact for a patient is commonly a routine visit to a provider with general symptoms that may be mild or not yet recognised as significant. The portal for entry into medical evaluation would likely involve standard electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiography (echo) and laboratory testing. Since this is the introductory pathway for the diagnosis of CA, let’s describe “red flag” type initial findings that would warrant further evaluation with more advanced testing.

Red flag historical and physical findings

“Red flag” symptoms and physical findings may be present individually, or in combination, and if present should stimulate the provider to be inquisitive and consider advanced testing to discern if CA is present. Conditions that are highly suggestive of CA and would warrant further confirmation include bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome, with a biopsy done during the surgery to make the diagnosis [8]; unexplained sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy, autonomic dysfunction with accompanying orthostatic hypotension can be telltale findings in multiple subtypes of amyloidosis; and gastrointestinal symptoms such as unintentional weight loss, early satiety, nausea, diarrhea, and constipation can indicate multisystem involvement [9].