Take-home messages

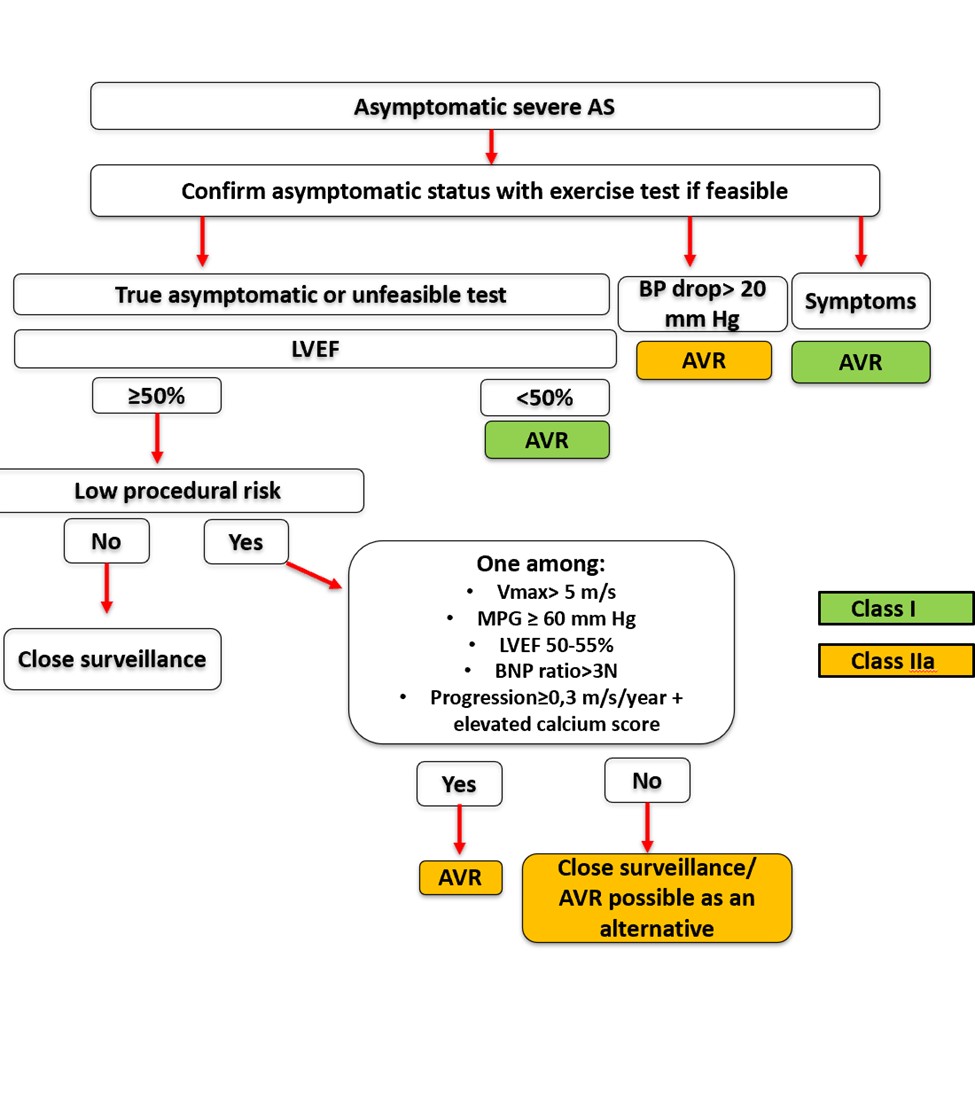

- Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) must be carefully measured; an LVEF below 55% should prompt consideration of aortic valve replacement (AVR), even in asymptomatic patients.

- In low surgical risk patients, search for high-risk features — such as elevated BNP, abnormal imaging findings, or myocardial fibrosis — to guide early AVR decisions.

- Exercise testing is essential in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis to unmask latent symptoms, assess blood pressure response, and evaluate functional capacity.

- Precise Doppler assessment using multiple acoustic windows is crucial to detect very severe AS (Vmax >5 m/s and/or mean gradient ≥60 mmHg).

- Close follow-up and patient education are vital when AVR is not immediately indicated; monitor for rapid progression (>0.3 m/s/year), elevated calcium score, or rising BNP to reassess intervention timing.

Introduction

Degenerative aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular heart disease in industrialised countries, observed in approximately 12% of individuals over 75 years old. Severe AS remains asymptomatic for a long time, but the progression of haemodynamic impairment and the timing of symptom onset vary between individuals. Symptoms such as dyspnoea, syncope, or angina typically appear first during exertion, then at rest, marking a critical turning point in the course of the disease. Indeed, life expectancy decreases significantly once symptoms develop, and without aortic valve replacement (AVR), the expected survival is classically 3 to 4 years after the onset of angina or syncope, and about 2 years if signs of heart failure are present [1]. Therefore, symptoms are central to the management of severe AS and should lead to AVR (class I recommendation) when clearly attributable to the stenosis [2]. However, the gradual progression of AS and the advanced age of affected patients complicate symptom identification. In asymptomatic patients, the focus of evaluation is firmly placed on identifying true severity and latent high-risk markers before clinical deterioration ensues. This necessitates a robust, multi-dimensional diagnostic framework, built around echocardiography but sometimes enriched by additional modalities including cardiac computed tomography (CT), stress testing, and circulating biomarkers.

Central figure. Management of asymptomatic severe AS according to 2025 ESC guidelines.

AS: aortic stenosis, AVR: aortic valve replacement, BP: blood pressure, BNP: brain natriuretic peptide, ESC: European society of cardiology, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, MPG: mean pressure gradient, Vmax: peak aortic jet velocity.

Echocardiographic diagnostic criteria

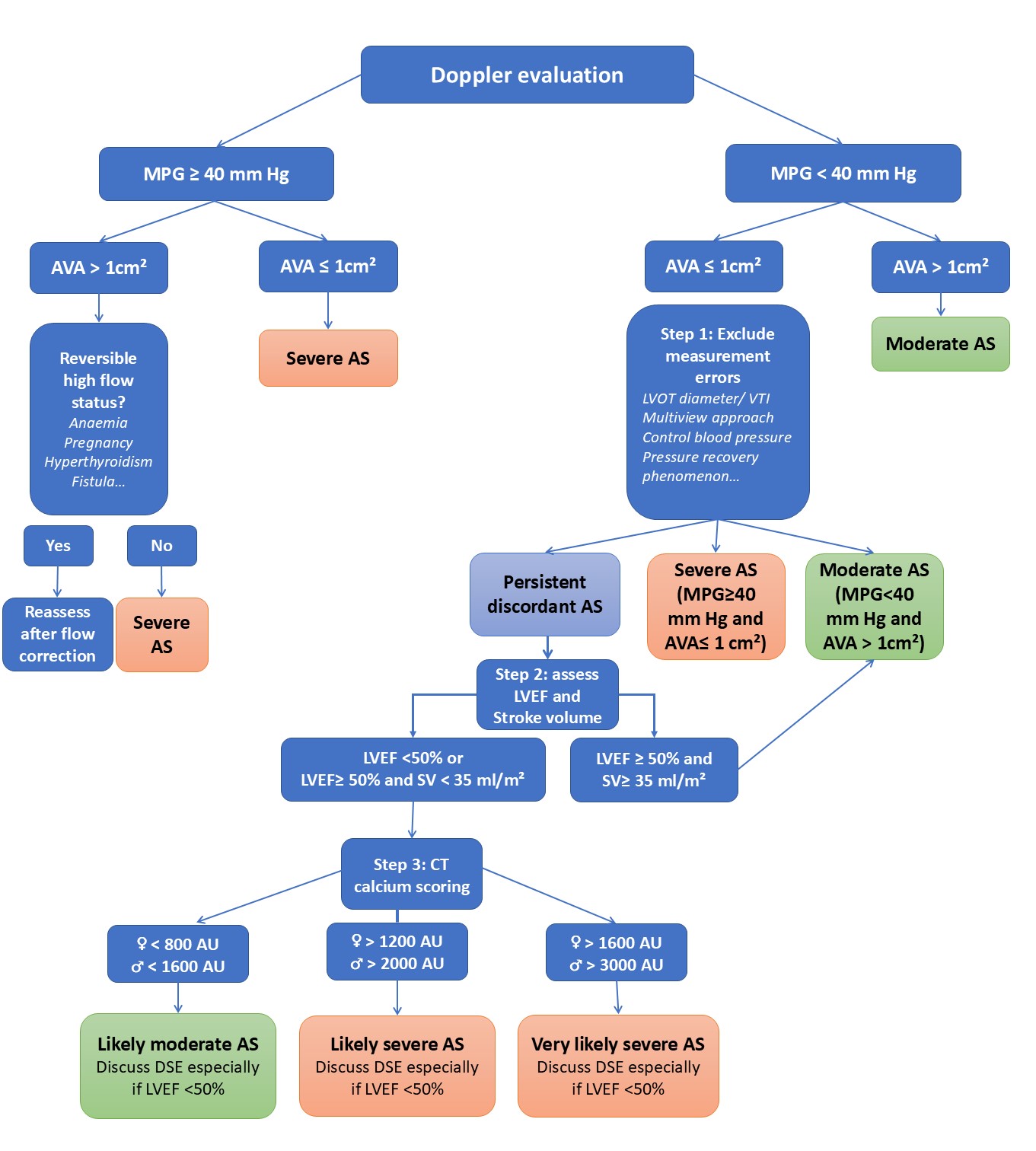

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) remains the cornerstone for evaluating AS severity. The fundamental criteria for defining severe AS are consistent across societies: a peak transvalvular velocity (Vmax) ≥4.0 m/s, a mean pressure gradient ≥40 mmHg, and an aortic valve area (AVA) ≤1.0 cm², typically calculated using the continuity equation. These parameters should ideally be concordant and measured under optimal haemodynamic conditions, avoiding confounders such as tachycardia, hyper/hypotension, or anaemia.

The accuracy of AVA calculation depends heavily on precise measurement of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) diameter and velocity time integral (VTI). Errors in LVOT assessment can significantly underestimate AVA, leading to misclassification. AVA indexing by body surface area (BSA) is encouraged, particularly in individuals with low BSA, with an indexed AVA ≤0.6 cm²/m² offering stronger specificity for severe AS [2]. Despite the clarity of these thresholds, discrepancies between gradients and AVA are frequent. These discordances highlight the need for refined classification and often necessitate supplementary imaging to distinguish true severe AS from pseudo-severe presentations.

Aortic stenosis subtypes: a brief clarification

While classifying AS into high-gradient, low-gradient, and low-flow subtypes is relevant — particularly when there is discordance between AVA and transvalvular gradients — a detailed haemodynamic breakdown is often unnecessary in the routine assessment of asymptomatic patients when all parameters are concordant. The typical presentation of severe AS is the normal-flow, high-gradient form, which represents the archetype of advanced disease.

In contrast, paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient AS — most commonly seen in elderly women with small, hypertrophied ventricles and preserved ejection fraction — presents diagnostic challenges. In such cases, confirmatory testing with stress echocardiography or aortic valve calcium scoring by multislice CT may be required. CT calcium scoring is particularly helpful: severe AS is unlikely with scores below 800 in women and 1,600 in men, becomes more likely above 1,200 and 2,000, and is highly likely with scores exceeding 1,600 in women and 3,000 in men [2].

In low-flow settings due to reduced left ventricular function, dobutamine stress echocardiography can help distinguish true severe AS from pseudosevere forms and assess contractile reserve. However, this technique requires experience and may be limited in the presence of atrial fibrillation. In the most complex cases, invasive haemodynamic assessment by cardiac catheterisation remains a valuable diagnostic tool to differentiate severe from moderate AS. Normal-flow, low-gradient AS should generally be considered moderate after a thorough reassessment of AS severity [2]. Classical low-flow, low-gradient AS with reduced ejection fraction constitutes a distinct entity and is not the focus here, as these patients are typically symptomatic (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A proposed algorithm for assessing AS severity.

AS: aortic stenosis; AU: Agatston unit; AVA: aortic valve area; CT: computed tomography; DSE: dobutamine stress echocardiography; MPG: mean pressure gradient; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOT: left ventricular outflow tract; SV: stroke volume; VTI: velocity time integral.

The challenge of asymptomatic severe AS

Managing asymptomatic patients is more complex than managing those with symptoms. The main issue lies in balancing the benefits and risks of AVR in asymptomatic individuals. The estimated annual rate of sudden death in asymptomatic severe AS is real but relatively low, around 1% per year. This risk must be weighed against the perioperative mortality risk of surgical AVR (1-3% in patients <70 years and 4-8% in older patients), along with potential valve-related complications [2]. Nonetheless , some asymptomatic patients undergo surgery too late, when myocardial damage is already (at least partially) irreversible, leading to high risks of heart failure and mortality even after successful intervention. Recent studies have revised upward the risk of sudden death in asymptomatic AS, and several meta-analyses suggest that early AVR may be beneficial, especially in low-risk surgical candidates [2]. Therefore, identifying poor prognostic markers in severe AS is crucial to the selection of asymptomatic patients who may benefit from earlier intervention. In practice, when a patient appears asymptomatic based on clinical history, assessment should proceed in stages to evaluate the indication for AVR.

Step1: Confirm true asymptomatic status with exercise testing

While exercise testing should be avoided in symptomatic patients, it carries minimal risk in asymptomatic individuals when performed in a suitable medical environment [2]. It helps identify falsely asymptomatic patients and assesses functional capacity and blood pressure response during exertion. The appearance of symptoms or a drop in systolic blood pressure of more than 20 mmHg during exercise is associated with poor prognosis and should lead to AVR [2] (Table 1). Although the prognostic value of increased mean gradient during exertion is debated, combining exercise testing with echocardiography can also reveal a drop in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and a rise in pulmonary pressures during exercise — both predictors of adverse outcomes. Cardiopulmonary or metabolic exercise testing can further help relate symptoms to valvular disease. Therefore, exercise testing (by any method) is essential when feasible and is a class I recommendation for patients considered asymptomatic by history [2]. A normal functional test provides reassurance, while an abnormal test serves as a diagnostic pivot point, even in the absence of conventional echocardiographic change. About one-third of patients with severe AS initially thought to be asymptomatic show symptoms during stress testing [2]. This is partly due to symptoms underreporting and also due to patients adapting to their condition by unconsciously limiting physical activity. Still, attributing symptoms to AS can be difficult — if not impossible — in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities causing dyspnoea, and in those unable to undergo stress testing.

Table 1. Recommendations for intervention (surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement [TAVR]) in asymptomatic severe AS (adapted with permission from [2]). 26/09 permission requested from ESC via GGC. The recommendations highlighted in blue in the table are unchanged from the previous 2021 guidelines ("classical recommendations"). The recommendation highlighted in pink has been newly proposed by the 2025 guidelines.

|

Recommendations for intervention in severe asymptomatic AS |

Class |

Level |

|

I |

B |

- very severe AS: Vmax >5 m/s and/or mean gradient ≥60 mmHg - severe calcification (ideally assessed by cardiac CT) and Vmax progression ≥0.3 m/s/an - Marked elevated BNP/NT-proBNP: more than 3 times age-sex corrected normal range, and confirmed on repeat measurement without other explanation - LVEF <55% without another cause |

IIa |

B |

|

IIa |

C |

|

IIa |

A |

AS: aortic stenosis; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; BP: blood pressure; CT: computed tomography; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement; Vmax: maximum velocity

Step 2: Accurately assess AS severity

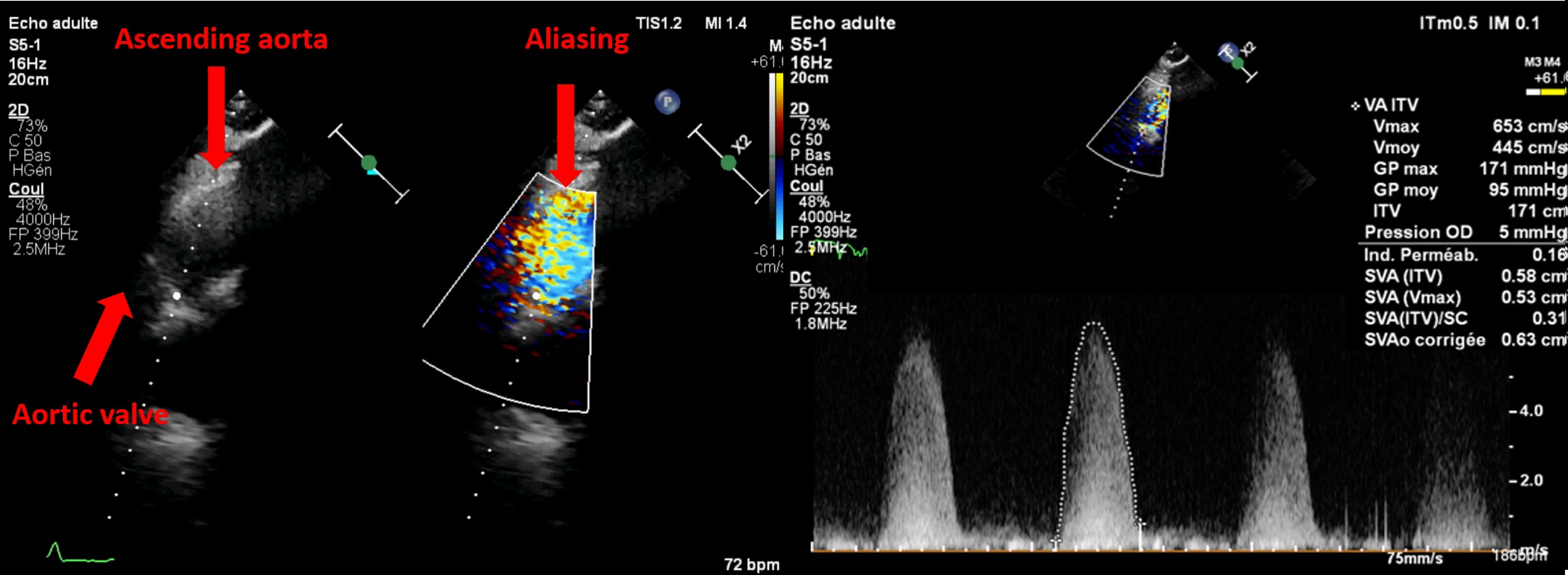

Severe AS has a worse prognosis than mild or moderate AS, and the degree of severity helps stratify risk even among severe cases [3–5]. About ten years ago, the Vienna group reported reduced event-free survival (death or AVR) as maximum velocity (Vmax) increased and introduced the concept of “very severe” or “critical” AS [3]. Based on this, U.S. guidelines in 2014 adopted a threshold of 5 m/s for early surgery in low-risk patients, whereas European guidelines used 5.5 m/s in 2012 and 2017 due to a lack of mortality data. Collaborative work with our team and Saint Philibert Hospital (Lomme) identified increased mortality starting at a Vmax of 5 m/s [4] or a mean gradient >60 mmHg [5] in over 1,100 asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with high-gradient (≥40 mmHg), severe AS with preserved LVEF. These and other multicentre studies [6] helped shape updated European guidelines which now recommend AVR (surgical or percutaneous, depending on age and access) for asymptomatic severe AS with Vmax >5 m/s and/or mean gradient ≥60 mmHg, if procedural risk is low [2]. Doppler measurements must be meticulously performed to avoid missing "very severe" AS. Also, apical-only views are insufficient. A multi-window approach (right parasternal++, suprasternal, supraclavicular, subcostal) using Pedoff or even standard 2D probes with colour Doppler (Figure 2) often detects higher gradients than apical views alone in at least one quarter of cases.

Figure 2. Interest of a multi view approach in asymptomatic aortic stenosis.

The use of a standard 2D probe allows visualisation of aliasing in the ascending aorta to obtain optimal alignment. In this patient, a Vmax of 4.3 m/s was recorded from the apical 5-chamber view, increasing to over 6 m/s from the right parasternal view — thus reclassifying the aortic stenosis from severe to very severe.

Step 3: Evaluate the haemodynamic impact of AS

To counter increased afterload, the left ventricle (LV) undergoes hypertrophic remodelling. Although LV hypertrophy is a physiological adaptation to chronic pressure overload from AS, the compensatory mechanisms eventually fail. The LV can no longer maintain normal stroke volume due to limited preload reserve — a condition called "afterload mismatch." This leads to diastolic dysfunction, then eventually systolic dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis. The presence of systolic dysfunction (LVEF <50%) is linked to high mortality and has long been a class I indication for AVR in asymptomatic patients [2]. However, this dysfunction appears late, and most symptomatic patients still have normal LVEF. Conversely, very few asymptomatic patients show LVEF <50% (around 0.4%), making this criterion rarely applicable in practice. A multicentre study (Amiens University Hospital, Saint Philibert Hospital, and Saint-Luc Brussels) of 1,678 patients with asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic severe AS and LVEF ≥50% divided patients into three groups: LVEF 50–55% (14%), 55–59%, and ≥60%. Five-year mortality was higher in the 50–55% group compared to the others, even after adjusting for age, comorbidities, and AS severity. This excess mortality persisted despite medical therapy or AVR, suggesting — as supported by other studies [6,7] — that the risk rises before the 50% threshold. The latest European guidelines still recommend AVR for LVEF <50% (class IB) but now propose (class IIaB) lowering the threshold to 55% [2] if the procedural risk is low (Table 1). Other promising markers include global longitudinal strain (GLS), which detects early systolic dysfunction. A meta-analysis found increased mortality risk in patients with preserved LVEF but GLS worse than -15% [8]. Still, this parameter isn't included in current surgical criteria, likely due to variability between ultrasound machines and limited availability.

Other prognostic parametres

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP; or N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]) levels correlate well with AS severity and New York Heart Association Functional Class. A rising BNP level over time is associated with symptom onset. Natriuretic peptides are also prognostic markers [9], but their interpretation must consider age and sex [9]. A BNP level exceeding 3 times the expected value (confirmed by repeated testing and without another obvious cause) may prompt AVR (surgical or transcatheter, class IIaB) in low-risk patients [2] (Table 1).

Other prognostic factors recently identified in severe AS include excessive LV hypertrophy, low indexed stroke volume (<30 mL/m²) [10], enlarged left atrial volume (>50 mL/m²) [11] impaired GLS (threshold around -15%) [8], or focal/diffuse fibrosis on cardiac MRI [2]. These markers aren't yet part of the surgical indication criteria but clearly identify patients at higher risk who require close monitoring. European guidelines state that, in the presence of multiple such risk factors in asymptomatic patients, surgical AVR may be discussed in low-risk patients, although there's insufficient evidence to support transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in this group [2]. In the light of the latest randomised trial on early surgery [12,13] or transcatheter aortic valve replacement [14], the latest guidelines now propose considering early intervention in low-risk patients as an alternative to close clinical and echocardiographic follow-up (class IIAB indication).

Monitoring

In patients with asymptomatic severe AS (confirmed by stress testing if possible) and no concerning features, close “armed” follow-up — clinical, echocardiographic, and biological (BNP) — is essential. Patients should be informed about warning symptoms requiring urgent consultation (angina, dyspnoea, syncope, or presyncope). Follow-up every six months is recommended [2]. Rapid AS progression, defined as a Vmax increase of >0.3 m/s/year, may warrant AVR (surgical or percutaneous) in low-risk patients, especially if the valve is heavily calcified [2] (Table 1). Rapid progression is linked to high event risk, particularly with severe calcification. New guidelines advise using CT-derived calcium scoring to assess this instead of subjective visual echo evaluation, due to the high reproducibility of CT scoring and the semi-quantitative, operator-dependent nature of echocardiographic calcification assessment.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic aortic stenosis requires a careful and proactive approach, as the absence of symptoms does not guarantee stability. Identifying high-risk patients relies on seeking prognostic factors beyond standard measures, particularly through accurate assessment of Vmax to avoid missing very severe AS, and precise evaluation of left ventricular function. A multimodal strategy combining imaging, biomarkers, and functional testing is essential to detect early myocardial impairment and guide timely intervention.

Impact on Practice

Clinicians must not rely solely on symptom absence in severe AS. Instead, a proactive, multimodal assessment — combining imaging, stress testing, and biomarkers — should be applied to identify high-risk asymptomatic patients. Early recognition of prognostic markers allows timely referral for AVR, improving outcomes while minimising irreversible cardiac damage.