or all ages, with a more pronounced benefit in patients at greater risk. Fibrinolysis may be reasonable only when primary PCI is not feasible in a timely manner, however, the associated risk in elderly patients is often high [7]. Non- ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients present a lower in-hospital mortality, but a medium/long-term mortality comparable to that of STEMI patients, a consequence of the greater number of comorbidities [4].

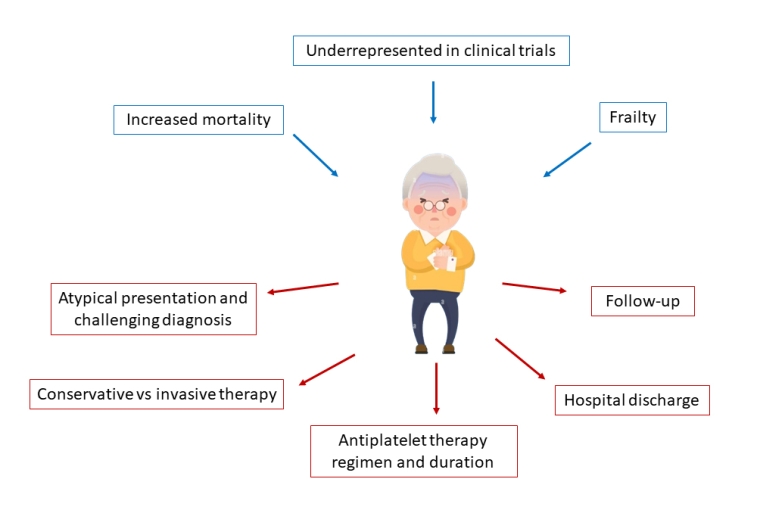

Elderly patients with NSTEMI less frequently receive pharmacotherapies and invasive assessment, present more complex coronary disease, have longer hospital stays, and are at higher risk of death. Indeed, as demonstrated in the ICON1 study, frail patients are reported to have a higher rate of a composite of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke, unplanned revascularisation, and major bleeding [1].

Frailty and multimorbidity may impact the degree of benefit derived from an invasive approach, and invasive management appears to be associated with only modest improvements in quality of life at 1 year follow-up in these patients. Furthermore, the presence of multimorbidities confers an increased risk of long-term adverse cardiovascular events, mainly driven by a higher risk of all-cause mortality [9]. Therefore, an individualised approach must be taken for these patients and a careful evaluation of the risk versus benefit balance is needed. To aid in decision-making in these patients, routine assessment of frailty (e.g. with the Rockwood Frailty Scale) and comorbidity (e.g. with the Charlson Comorbidity Index) is recommended [4]. This careful assessment allows frail patients at high risk of cardiovascular events and low risk of complications to undergo invasive strategy and/or optimal medical therapy, preferring optimal medical therapy alone for those patients at lower risk of future cardiovascular events, but with a high risk of developing procedural complications. For those patients for whom any form of treatment is deemed futile, a palliative end-of-life care approach should be adopted [4].

Pharmacotherapy

In general, the same medical treatment strategies are recommended in older and younger ACS patients, but due to the exclusion of “very old” patients from major RCTs, caution is requested when applying trial results to this patient population [4]. Pharmacotherapy should be adapted to renal function, comorbidities, comedications, frailty, and specific contraindications. Some strategies can be applied to reduce bleeding events: i.e., shortening of double antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) duration (<12 months) and de-escalation of intensity treatment. Six-month DAPT after DES implantation in a cohort of elderly ACS patients is safe with regard to ischaemic events [10]. A reduction in bleeding risk with no increase of ischaemic events with 1-month as compared to 6-month DAPT has been demonstrated in a cohort of patients at high bleeding risk (HBR); the most used P2Y12 receptor inhibitor was clopidogrel [10]. Regarding prasugrel, a dose reduction from 10 mg to 5 mg per day is currently recommended in patients ≥75 years. However, prasugrel 5 mg per day as compared to clopidogrel increases the bleeding risk in ACS-PCI patients, with no reduction in ischaemic endpoints [10].

The overall safety of ticagrelor as compared with clopidogrel was not found to be age-dependent [11], but it has been associated with a higher risk of bleeding and death than clopidogrel [12]. In non-ST-elevation (NSTE)-ACS patients older than 70 years, DAPT with clopidogrel led to fewer major and minor bleedings and a trend towards a reduced rate of the combined net clinical endpoint as compared with DAPT with a potent P2Y12 receptor inhibitor [13]. Finally, in ACS-PCI patients with atrial fibrillation the recommended therapeutic strategy is a short period (generally up to 1 week, or up to 1 month in patients at high ischaemic risk) of triple antithrombotic therapy (TAT) with direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) and DAPT (with aspirin and clopidogrel) followed by dual antithrombotic therapy (DAT) with DOAC at the recommended dose for stroke prevention and a single antiplatelet (preferably clopidogrel) for up to 12 months [4]. In older HBR patients, DAT should be shortened to ≤6 months according to clinical judgment, by withdrawing the antiplatelet.

In ACS patients managed medically, i.e., for presentation beyond 12 hours or for those who cannot undergo reperfusion treatment, available data from RCTs support DAT over TAT, with a single antiplatelet agent (most commonly clopidogrel) for at least 6 months.

Gender differences

Several studies have examined age-stratified sex differences in care and outcomes of ACS patients and have shown that disparities may differ according to age. Worse outcomes in women have been attributed to older age and a greater burden of comorbidities, but also to a lower revascularisation rate. An analysis of elderly patients treated with PCI, found significantly higher mortality among women with STEMI, as compared with men [14]. No current data support a different management of ACS based on sex, but women with ACS are often managed differently than men. They often go to the emergency room late after the onset of symptoms and are less likely to receive coronary angiography, timely revascularisation or secondary prevention medications [4]. Of note, several studies have reported that a disproportionately low proportion of women are recruited to RCTs. Increased representation of female patients with ACS in future clinical trials is desirable to collect more information about their optimal management [4].

Prognostic stratification

Clinical presentation

Elderly patients with ACS present with atypical symptoms in 8.4% of cases (dyspnoea, diaphoresis, nausea, and syncope or pre-syncope) with frequent delays to first ECG. Furthermore, the initial ECGs are less likely to diagnose ACS. On the other hand, symptoms are often underreported, due to difficulties in expression, and to cognitive impairment in elderly patients. They are less likely to call emergency services or to go to hospital on their own, and the occurrence of in-hospital ACS (during hospitalisation for non-cardiac reasons) is more frequent.

Comorbidities

Diabetes

In general, 20% of the elderly population has diabetes, and a similar proportion have undiagnosed diabetes. Complications and management in the elderly vary according to hyperglycaemia duration, personal background, and comorbidities. Usually, glycaemic targets are less stringent, due to difficulties in achieving optimal glycaemic control in this subgroup of patients. Approximately 60% of diabetic patients develop cardiovascular disease and diabetic patients have a worse outcome both at 30 days and at 1 year follow-up.

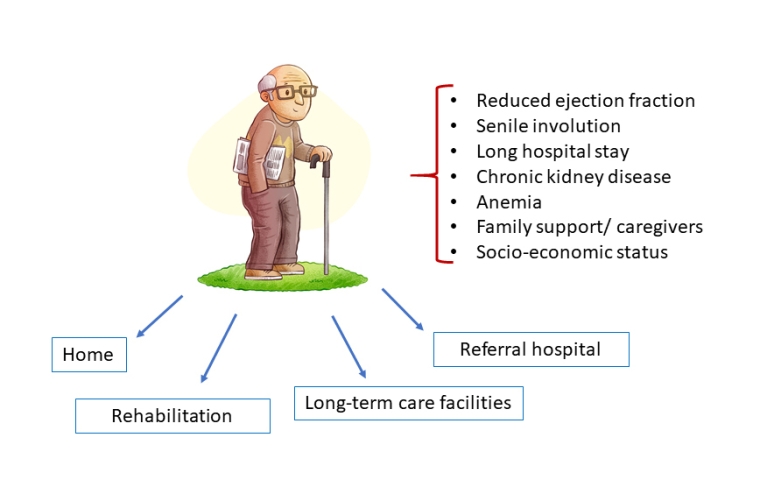

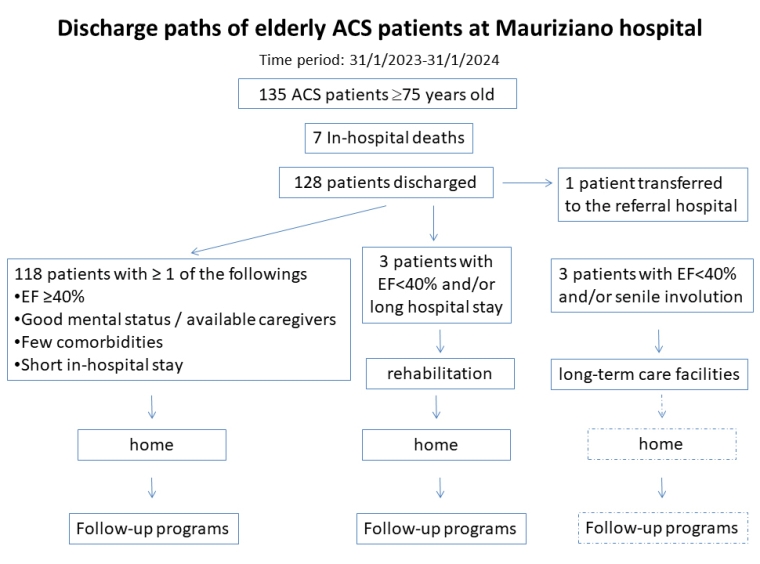

Chronic kidney disease

A series of studies documented the prognostic importance of chronic renal failure in ACS. In particular, patients with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <30 ml/min have a worse hospital prognosis compared to those with GFR between 30-60 ml/min or with normal GFR (mortality rate 12.2%, 5.5%, 1.4%, respectively).

Peripheral arterial disease

The coexistence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) with ACS leads to a worse clinical course and prognosis. Moreover, PAD has a higher incidence in diabetic patients.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

In stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the risk of ACS is 2-3 times higher than in non-COPD patients and is up to 5 times higher in a flare-up phase. Special attention is required for elderly patients with both ACS and COPD, both in the acute phase (adequate and prompt care of O2/CO2 balance in order to limit additional myocardial damage due to discrepancy, antibiotic and anti-inflammatory therapy) and thereafter (favouring betablockers as bisoprolol, for example, and monitoring the right heart function and pulmonary pressures, adding, if needed, right heart catheterisation especially in elderly women with coexistent rheumatologic disease). Vaccination programs are warranted.

Active cancer

Cancer itself enhances both bleeding and thrombotic risk. These patients represent a challenge both for the clinical cardiologist, who should select those who may or may not undergo reperfusion according to prognosis and vital status including patient’s choice, and for the interventionalist, who should adapt intraprocedural antithrombotic drugs to the bleeding risk and choose the best interventional strategy. This may include limiting the number of stents, selecting special stents [10], or using drug-eluting balloons when possible to limit the thrombotic risk.

Left ventricle ejection fraction

Haemodynamic instability and cardiogenic shock are more frequent in elderly hospitalised patients. The percentage of patients with an ejection fraction (EF) <40% after an ACS is about 20% and the 12-year survival rates in patients with EF >50%, EF between 35-49% and EF <35% are 73%, 54% and 21%, respectively [15]. Moreover, another important aspect to take into consideration is the early onset of post-MI heart failure which represents the most important predictor of long-term mortality [15]. When indicated, age per se, is not a contraindication for an intracardiac defibrillator (ICD) or cardiac resynchronisation devices in a situation of unrestricted economic resources. Of course, these should be implanted when life expectancy is more than one year and take into consideration the cognitive, clinical, and vital status of the patient. In particular, the implantation of an ICD in post-ACS patients ≥80 years old with residual left ventricle EF <30% (as assessed at least 40 days after ACS or revascularisation) should be evaluated on an individual basis.