Keywords

autoimmune, cancer, infection, pericarditis, treatment

Abbreviations

AMI: acute myocardial infarction

ANA: anti-nuclear agents

CRP: C reactive protein

ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate

ESRD: end-stage renal disease

NSAIDs: non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs

PCIS: post cardiac injury syndromes

SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus

TB: tuberculosis

Patient-oriented messages

What are the causes of pericarditis?

While pericarditis is idiopathic in almost 90% of cases and is generally due to viral infections, secondary pericarditis may be: 1) infective, and especially related to tuberculosis (TB); 2) associated with immune diseases such systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); rheumatoid arthritis; 3) associated with kidney failure; 4) associated with acute myocardial infarction (AMI); 5) associated with pericardiotomy; and 6) associated with radiotherapy. Moreover, pericardial effusions may be related to a neoplastic condition, first of all to metastatic neoplasms or cancer therapy. [1].

What is the treatment of a pericarditis?

The general treatment of acute pericarditis includes drugs for pain and inflammation such as aspirin, ibuprofen and, above all, colchicine. Any form of secondary pericarditis requires the specific treatment, such as antibiotics or antimycotics, for the causal disease. Only pericarditis due to immunotherapy can be treated with cortisone [2]. In cases of large effusions, fluid drainage, treatment of cancer metastasis and eventually, pleuro-pericardial fenestration, are the required treatments [3].

When is pericarditis a serious illness and when is it not?

More than 80% of cases of acute pericarditis and more of 50% for those admitted to hospital in developed countries are idiopathic with a self-limiting, benign course and an overall good prognosis. However, some secondary causes, like pericarditis associated with cancer may lead to death. Infective pericarditis, like TB, or some forms linked to autoimmune diseases may be difficult to treat or cure and evolve into constrictive pericarditis or other complications.

Impact on Practice statement

When is secondary pericarditis a real management problem and when may it complicate?

Every form of secondary pericarditis has its own profile but generally leads to an effusion of exudative type which are often haemorrhagic or inflammatory. This may evolve into a chronic and progressively constrictive form of pericarditis that is very difficult to manage [4]. Consequently, any kind of secondary pericarditis should be referred to a specialised point of care with skills in the specific therapies required for management.

Every cardiologist should therefore be able to distinguish a ‘simple’ idiopathic pericarditis with a low probability of evolution (and can then reassure the patient about a favourable prognosis) from a secondary form of the disease.

Take-home messages

- What are the most frequent causes and how to diagnose the different forms of pericarditis

- Which forms of pericarditis most frequently evolve?

- How to distinguish an incessant or recurrent or chronic pericarditis from a secondary form and what are the most probable secondary forms?

What are the most frequent causes and how to diagnose the different forms of pericarditis

When the first episode of acute pericarditis occurs, a routine diagnostic practice according to the 2015 ESC Guidelines [1] should include a careful patient history (including data about travel abroad, history of autoimmune diseases, and a careful search for signs and symptoms of an unknown neoplastic condition), clinical exam, electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, echocardiogram, and routine blood samples, together with inflammatory indexes (C-reactive protein [CRP], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]), troponin and thyroid function tests.

When a secondary cause of pericarditis is suspected, the blood sample should also include autoimmune diseases markers (ANA), QuantiFERON-TB Cold and tumour markers.

Pericarditis due to autoimmune diseases is frequent (2-24%) and may have variable prognosis. Asymptomatic effusions may not require aggressive treatment, while clinically significant involvements should be extensively treated.

While primary pericardial cancers are rare, pericardial involvement in neoplastic diseases is frequent, particularly in cases of metastasis, but may also be a side effect of many chemotherapy agents, immune therapies or radiotherapy [5]. It has been estimated that about 30% of pericardial effusions of unknown origin may be due to cancer, sometimes with evolution to cardiac tamponade and, less frequently than in the past, to a constrictive pericarditis [6, 7].

Tamponade may require pericardiocentesis. If the effusion is due to chemotherapy, a temporary suspension, modification or even an interruption of the causative drug may be considered, if possible, during a multidisciplinary discussion. Sometimes a re-challenge of the same therapy may be considered.

A comprehensive epidemiology and a list of the clinical characteristics of pericarditis and secondary pericarditis are presented in Table 1 [1].

Table 1. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of secondary pericarditis.

Aetiology of Pericarditis

- Idiopathic

- Frequency: Africa: 15%; Europe and United States: 80–90%

- Notes: Generally benign and self-limiting

- Evolution: 15–30% may evolve into recurrent/incessant forms, <1% constriction, <2% tamponade

- Therapy: NSAIDs + colchicine

- Viral

- Frequency: 30–50%

- Notes: Enterovirus (Coxsackie, echoviruses), Herpesvirus (Epstein-Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus), Adenovirus (especially in children), Parvovirus B19, Coronavirus

- Evolution: Still few data about evolution of Coronavirus

- Therapy: NSAIDs + colchicine

- Bacterial

- Frequency: <1% (Europe) to 2–3% (mainly Africa); 1–4% (Italy, Spain, France), up to 70% (Africa); rare (largely unknown)

- Notes: MB tuberculosis (common; others rare), Purulent pericarditis (Pneumo, Meningo, Gono, Strepto, Staphylo, Haemophilus), Coxiella burnetii, Borrelia burgdorferi

- Evolution: Related to ethnicity and immunodeficiency. High probability of evolution in constrictive forms

- Therapy: NSAIDs + colchicine + specific agents therapy

- Fungal

- Frequency: Rare

- Notes: Histoplasma, Aspergillus, Blastomyces, Candida

- Evolution: More likely in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts

- Therapy: (not specified)

- Parasitic

- Frequency: Rare

- Notes: Echinococcus, Toxoplasma

- Evolution: (not specified)

- Therapy: (not specified)

- Autoimmune and auto-inflammatory

- Frequency: 2–24%

- Notes:

- Systemic autoimmune (SLE, Sjogren syndrome, RA, scleroderma)

- Systemic vasculitis (eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis or allergic granulomatosis, previously named Churg-Strauss Syndrome, Horton disease, Takayasu disease, Behcet syndrome)

- Autoinflammatory diseases (familial Mediterranean fever, tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome)

- SARS CoV2 vaccination

- Other (sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel diseases)

- Evolution: Clinical suspicion related to the base illness and to serologic autoimmune evaluation. Possible evolution in large effusions and constrictive forms

- Therapy: NSAIDs + colchicine + immunosuppression (azathioprine, anakinra), IVIGs

Viral pericarditis

Most cases of a first attack of acute pericarditis are presumably viral; a recent clinically apparent viral infection of the upper respiratory tract or gastroenteritis has been documented in almost 40% of cases. The identification of the causative virus is generally futile, given the lack of any impact for treatment implications, and, generally, on the prognostic evolution of the condition.

In the last 2 years, the development of a new-onset pericarditis, associated with COVID- 19 infection in 1.5-2.8 % of cases, has been described [8]. Notably, in contrast to acute myocarditis, pericarditis was more common in older subjects.

An autoinflammatory mechanism may result from activation of the inflammasome by a cardiotropic virus or a nonspecific agent in a genetically predisposed individual who has abnormal innate immunity.

Bacterial pericarditis

Bacterial pericarditis is relatively rare in high-income countries. Tubercular pericarditis is the most common form worldwide and is found mainly in low-income countries, where 90% of people with an HIV infection and 50-70% of non-HIV infected patients may show a significant pericardial effusion. Moreover, TB pericarditis entails a very high mortality: about 25% at 6 months in non-HIV subjects and approximately 40% in those with an HIV infection. It may also develop in subjects with immunodepressions of other origins, like cancer therapies. In general, a severe complication which occurs after 6 months from an effusive-constrictive form may be a constrictive pericarditis.

A true purulent pericarditis is rare (< 1%). The most common infective agents are staphylococci, streptococci, pneumococci, with associated lung lesions (empyema 50%, pneumonia 33%). Staphylococcus aureus and fungi are the most common causative agents after thoracic surgery and immunodepression. If a purulent pericarditis is suspected, an urgent pericardiocentesis is required for diagnosis and treatment.

In tuberculosis, an effective therapy for pericarditis over the course of 6 months is generally the association during 2 months of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, followed by isoniazid and rifampicin for the remaining 4 months. A therapy duration of longer than 6 months appears to be of no benefit, increases costs, and is subject to lower compliance. An empiric IV antibiotic therapy should immediately begin followed by the specific therapy suggested by microbiology tests once the diagnosis is established.

Autoimmune pericarditis

Among acute or recurrent pericarditis patients, 5-15% may suffer from an overt or concealed systemic autoimmune disease. SLE, Sjogren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and scleroderma are the most common diseases leading to pericardial involvement, but systemic vasculitis Behçet's Syndrome, sarcoidosis and bowel inflammatory diseases may also lead to acute or recurrent pericarditis [9].

It is rare that pericardial involvement is the first expression of these conditions. Most patients have a clear diagnosis of the basic syndrome according to the clinical symptoms and signs. In any case, if a clinical condition leads to the suspicion of an autoimmune disease, proper investigations must be undertaken. The first investigation should include a search for ANA positivity, associated with many autoimmune diseases, notably SLE.

Pericardial involvement is a common occurrence in RA, affecting about one-third of patients with a prevalence from 30-50%, and is frequently paucisymptomatic. Fewer than 10%, generally male, develop a clinically relevant pericarditis with an elevated rheumatoid factor and nodular RA.

There is a recently recognised new form of pericarditis that is triggered by an autoimmune mechanism related to the mRNA vaccine platforms. This includes any mRNA vaccine, including the COVID-19 vaccine. In one study including 38,615,491 adults vaccinated with at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 0.001% were hospitalised with pericarditis in the 1–28 days after any dose of vaccine. In another series of 2,000,287 individuals receiving at least 1 vaccination dose, pericarditis developed in 37 cases, mainly after the second dose with a median onset of 20 days after the most recent vaccination.

It is probable that some forms of ‘autoimmune’ pericarditis are in reality ‘autoinflammation’, with some relevant differences, such as the involvement of the innate immune system, mediated by cytokines (primarily IL-1) without the involvement of autoantibodies, very high levels of CRP, fever, systemic involvement with acute attacks which tend towards a complete resolution and which may be treated with specific inhibitors such as anakinra.

As in other forms of pericarditis, in addition to the common anti-inflammatory therapy with NSAIDs and colchicine an aggressive treatment of the systemic disease with its specific therapies is required. Asymptomatic effusions revealed during routine echocardiograms may not require any treatment apart the intensification of the disease-specific drugs and close monitoring. Data on immunosuppression results for these forms of pericarditis are still lacking and, specifically here, prednisone, azathioprine, intravenous immunoglobulins and anakinra may be used over the common NSAID and colchicine therapy.

End-stage kidney / renal disease pericarditis

In end-stage renal disease (ESRD), three different forms of pericarditis may be encountered: a) uremic pericarditis which occurs no later than 8 weeks from the beginning of the dialysis; b) dialysis pericarditis, after 8 weeks of treatment; c) a constrictive form, which is rarely seen nowadays. An acute form with chronic effusion is commonly encountered while a chronic constrictive form is rarely seen.

The global incidence of pericarditis in ESDR patients has decreased in recent times to 5% in those beginning dialysis. The occurrence of pericarditis during dialysis is considered to between 2-21% but recent data are lacking.

Other forms

A particular form of acute pericarditis may occur in the first days after an acute myocardial infarction, after cardiac surgery, after chest trauma (although rare) or after interventional procedures such as percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), pacemaker implantation, or radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation during an hospital stay (the so-called ‘post-cardiac injury syndrome’ [PCIS]) which seems to have an ‘autoimmune’ origin and generally disappears spontaneously in a few days, with or without a specific treatment, which, mainly in CAD patients, is with aspirin.

Although relatively rare, after the huge amelioration of technique, acute pericarditis may occur after radiotherapy involving the chest or cardiac region, mainly for left breast cancers and for lung cancers. This requires the same therapy as for the other pericarditis causes and rarely becomes constrictive.

Which forms of pericarditis most frequently evolve?

Tamponade

The answer is alluded to in the previous chapter, and any kind of evolution is generally related to the aetiology of the pericarditis.

The probability of tamponade is strictly related to the impairment between fluid production and drainage velocity. The first depends on the seriousness of inflammation, which in turn leads to a severe degree of vessel permeability and a rapid transition of liquid into the pericardial sac, and/or eventually bleeding, i.e., of a pericardial metastasis; the latter is conditioned by the function of the lymphatic drainage system.

It has been evaluated that about 30% of acute tamponade requiring drainage are due to a neoplastic form.

Chronic forms and constrictive forms

Any aetiology related to an infectious or inflammatory disease may, through a chronic inflammatory persistent condition, lead to a fibrous reaction and to the thickening of the pericardial leaflets. The kind of pericardial fluid (transudate vs exudate) heavily influence the possible chronic evolution.

How to distinguish an incessant or recurrent or chronic pericarditis from a secondary form and what are the most probable secondary forms?

Incessant pericarditis in defined as occurring during more than 4 - 6 weeks without any kind of remission, while recurrent pericarditis is a new event after a symptom-free interval of 4 to 6 weeks and chronic pericarditis lasts >3 months. While the recurrent form is generally not secondary pericarditis, the other two must be differentiated by secondary forms, and frequently, at least for chronic pericarditis, they are themselves a secondary form.

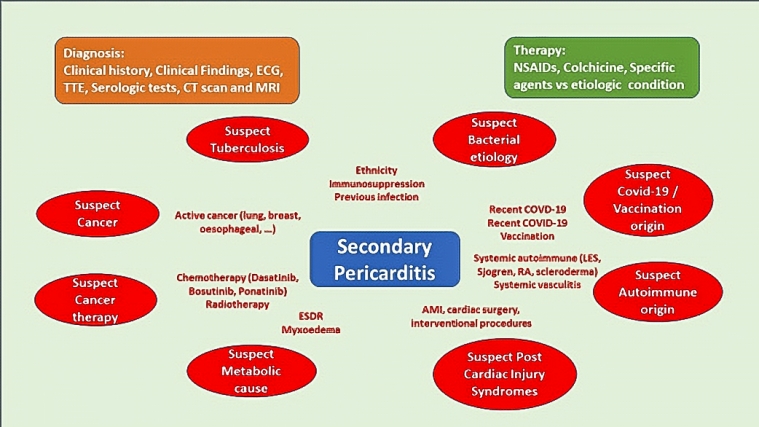

The epidemiology, the clinical and the serologic characteristics are generally lead to the correct aetiological diagnosis. (See “Tip and tricks about acute pericarditis” Fava et al and the Central Figure).

Sometimes the diagnosis process is easy and linear, while many other cases require complicated and difficult diagnostic paths, including, among other issues, a strong collaboration with an imaging expert. These situations may require magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans over the more ‘common’ echocardiography.

The cardiologist must make every treatment effort possible when confronted with a patient with suspected secondary pericarditis given the bad prognostic implications of many of these illnesses.

Conclusions

While acute idiopathic pericarditis is the most common presentation of pericardial diseases and it generally has a benign course, secondary pericarditis can have lots of complications and recurrences and, moreover may be associated with extremely serious infectious and non-infectious illnesses.

Consequently, secondary pericarditis requires an in-depth clinical process to investigate them, and to reach to a correct aetiologic identification to allow for the best possible treatment.

The patient’s history, which should include the analysis of the conditions that may be susceptible to pericarditis – the exclusion or confirmation of internal medical pathologies (cancer!) or geographical exposures (TB!) – is the mainstay of the diagnostic process of pericarditis.

The second essential great help in the diagnosis and guidance for tailored treatment are the new imaging studies, and when the Echocardiography is not resolutive, CT scan and mainly MRI may lead to a clear definition of the picture.

The awareness of the diagnostic and etiologic features of pericarditis is key for a proper treatment and the prevention of complications.

In patients with recurrent or constrictive pericarditis or in those dependent on corticosteroids, targeted therapies with IL-1 blockers or other immunomodulators represent promising therapies.