Keywords

aldosterone, hypokalaemia, primary hyperaldosteronism, secondary hypertension

Abbreviation list

ARR: aldosterone-to-renin ratio

AVS: adrenal vein sampling

BP: blood pressure

MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

PA: primary aldosteronism

Take-home messages

- Consider PA screening in all hypertensive patients, as it is the most common cause of secondary hypertension.

- Controlled conditions (normal sodium intake and potassium levels, withdrawal of interfering medications) optimise the accuracy of biochemical testing. Testing under interfering drugs is acceptable if withdrawal poses significant risks (e.g., severe hypertension, high cardiovascular risk).

- Adrenal computed tomography scan should be performed in confirmed PA to rule out adrenocortical carcinoma.

- Unilateral adrenalectomy should be considered for patients with confirmed lateralised PA (by AVS), who have no surgical contraindications and wish to undergo surgery.

- Medical therapy with spironolactone is the first-line option for patients who are not surgical candidates, decline surgery, or have non-lateralised PA.

Patient-oriented message

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is the most common cause of secondary hypertension, and screening should be considered for all patients with high blood pressure (BP). Compared to essential hypertension, PA is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular and renal complications. Treatments specifically targeting PA can reduce these risks. Screening for PA involves a simple blood test, usually performed under controlled conditions to ensure accurate results. If PA is confirmed, a computed tomography scan of the adrenal glands, and sometimes a specialised test called adrenal vein sampling (AVS), will help determine the best treatment. Depending on the results, treatment may involve surgery to remove one adrenal gland or medical therapy with a specific drug such as spironolactone.

Pathophysiology of primary aldosteronism (PA)

Aldosterone is a steroid hormone synthesised in the zona glomerulosa, the outermost layer of the adrenal cortex. Its primary role is to regulate water–electrolyte balance and blood pressure (BP). Aldosterone secretion is mainly controlled by angiotensin II and plasma potassium levels.

Hyperaldosteronism refers to excessive aldosterone production. It frequently causes hypertension, which may be mild but is often severe and resistant to standard anti-hypertensive therapy. It is an underdiagnosed cause of resistant hypertension. The classic presentation includes hypertension and hypokalaemia; however, in clinical practice, many patients do not display significant hypokalaemia. Moreover, there is no clear consensus about its threshold: based on our experience, we suggest that K<3.5 is hypokalaemia, but in the literature this threshold varies between 3.5 and 3.9 mmol/l.

Cardiovascular effect of hyperaldosteronism

Aldosterone promotes hypertension primarily by inducing renal sodium and water retention. This process is mediated through the activation of mineralocorticoid receptors and the upregulation of epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) in the distal nephron, which simultaneously enhances potassium excretion. Excess aldosterone also suppresses plasma renin activity.

Beyond its hypertensive effects, hyperaldosteronism exerts direct harmful actions on the cardiovascular system and kidneys, partly independent of BP. Compared with essential hypertension, PA is associated with:

- Target organ damage: left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, arterial stiffness, microalbuminuria, and reduced glomerular filtration rate.

- Metabolic alterations: insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.

- Cardiovascular events: increased risk of stroke, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure [1].

Primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism

Hyperaldosteronism is classified into two forms with overlapping clinical presentations but distinct biochemical profiles.

- Primary hyperaldosteronism (PA):

PA is defined by inappropriate, autonomous aldosterone secretion by the adrenal glands. It is characterised by elevated aldosterone blood levels with suppressed renin activity. PA represents the most frequent endocrine cause of secondary hypertension. Its prevalence is estimated between 5–14% among hypertensive patients in primary care and up to 30% in specialised centres, increasing with hypertension severity [2]. The main causes are unilateral aldosterone-producing adenomas (30%) and bilateral adrenal hyperplasia of the zona glomerulosa (60%).

- Secondary hyperaldosteronism:

This form results from excessive aldosterone secretion secondary to elevated renin production, usually due to an extra-adrenal condition. Underlying causes include renal artery stenosis, tubulopathies, oedematous states (congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis with ascites), severe uncontrolled hypertension, pheochromocytoma, and, rarely, renin-secreting tumours.

Who should be screened for PA?

International recommendations

International guidelines show broad consensus on the main clinical situations in which screening for PA is indicated.

Screening is recommended by all major guidelines in the following cases [3-7]:

- Resistant hypertension (BP >140/90mmHg despite triple therapy including a thiazide diuretic).

- Hypertension with hypokalaemia (spontaneous or on diuretics).

- Hypertension associated with an adrenal incidentaloma ≥1 cm.

Screening is recommended by most of the guidelines in the following cases:

- Hypertension with complications disproportionate to its level or duration [4-6].

- Hypertension with a family history of early-onset hypertension or stroke (<40 years) [3-5].

- Hypertension with tetany or muscle weakness [3-5].

Screening is recommended by at least one guideline in the following cases:

- Severe hypertension (BP≥180/110mmHg) [6].

- Hypertension onset before the age of 40 [7].

- Hypertension with obstructive sleep apnoea [3].

- All adults with BP ≥140/90mmHg [4,5].

Should we screen all hypertensive subjects for PA?

Recent international recommendations advocate for systematic PA screening in all patients with hypertension, based on two main considerations: (i) High prevalence of PA, even in the absence of hypokalaemia or resistant hypertension; (ii) Increased cardiovascular risk associated with inappropriate aldosterone secretion, which promotes disproportionate target organ damage independent of BP levels [1,4,5].

A universal screening strategy would offer several advantages. If performed before initiation of antihypertensive therapy, it would simplify the diagnostic process by avoiding the confounding effects of interfering medications. It would also reduce the risk of missed diagnoses, particularly in patients managed exclusively in primary care. Importantly, PA remains a potentially curable cause of hypertension.

Nevertheless, while PA is the most frequent cause of secondary hypertension, the cost-effectiveness of systematic screening must be carefully evaluated. The societal and healthcare costs of universal testing may not be sustainable in all contexts. Depending on local resources and healthcare organisations, it may be more pragmatic to prioritise screening in populations with a higher prevalence of PA — such as patients with severe or resistant hypertension, or those referred to specialised centres — rather than in the general hypertensive population [2,8].

Moreover, a high pre-test probability improves the interpretability of hormonal assays. The diagnostic process can be challenging, as the spectrum from low-renin essential hypertension to overt PA sometimes blurs the distinction between these entities.

Further research directly comparing systematic versus targeted screening strategies is warranted to determine the most effective and cost-efficient approach.

How to screen for PA [4,7]

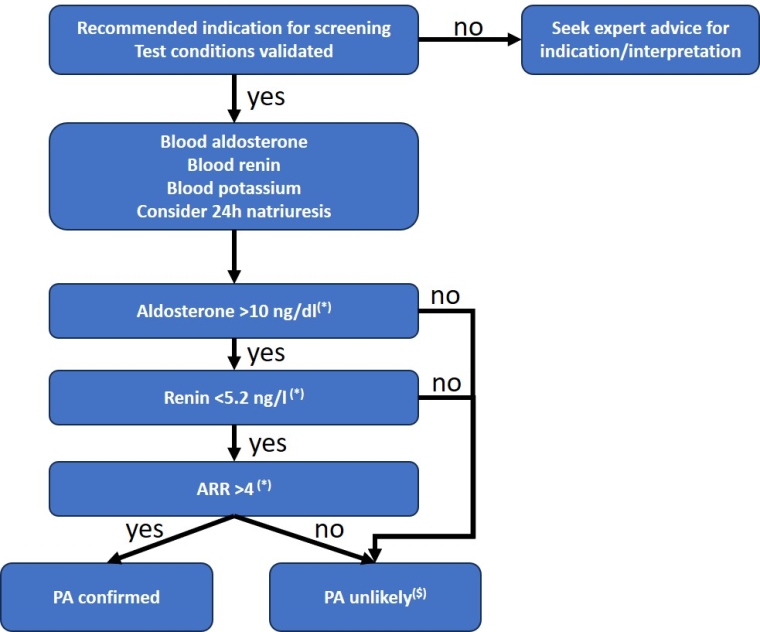

Central Figure. Algorithm for aldosterone, renin and ARR interpretation.

(*) Cut-off values for aldosterone in ng/dl as measured by immunoassay and for direct renin in ng/l. See Table 1 for other techniques/units

($) Retesting (or seeking expert advice) may be useful if the pre-test probability is high, such as for patients with resistant hypertension, hypokalaemia (spontaneous or on diuretics), adrenal incidentaloma ≥1 cm, and hypertension with complications disproportionate to the level and duration of hypertension.

Which laboratory test?

The aldosterone-to-renin ratio (ARR) is the reference screening test for PA.

Because aldosterone and renin are continuous biological variables, defining diagnostic cut-offs is challenging: thresholds directly impact test sensitivity and specificity and vary depending on assay methodology. Ideally, each laboratory should establish its own diagnostic thresholds. In the absence of local validation, cut-offs can be extrapolated from published reference values (Table 1).

Table 1. Suggested ARR thresholds for PA diagnosis according to dosage technique and measurement unit.

| Aldosterone concentration (immunoassay) |

Aldosterone concentration (liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol/l | ng/dL | pmol/l | ng/dL | ||

| Direct renin concentration |

mUI/ml | >70 | >2.5 | >52 | >1.8 |

| ng/l | >111 | >4 | >82 | >2.8 | |

| Plasma renin activity |

ng/mL/h | >555 | >20 | >416 | >15 |

ARR: aldosterone-to-renin ratio; PA: primary aldosteronism

The diagnosis is based on detection of an abnormally elevated ARR, i.e., when renin is low or inhibited and aldosterone inappropriately elevated relative to renin level.

In practice, ARR should be calculated only when aldosterone >10 ng/dL (277 pmol/L) by immunoassay or >7.5 ng/dL (208 pmol/L) by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry and renin ≤8.2 mIU/L (5.2 ng/L) or plasma renin activity ≤1 ng/mL/h. ARR should not be calculated if aldosterone is <10 ng/dL (277 pmol/L) by immunoassay.

Optimal conditions for ARR measurement

To maximise diagnostic accuracy, aldosterone and renin should be measured concurrently under controlled conditions:

- Morning sampling, at least 2 hours after awakening.

- After 5–15 minutes in the seated position.

- While on a standard sodium diet (Table 2).

- With normal serum potassium levels (Table 2).

- After withdrawal of interfering medications (Table 2). Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and α-blockers are considered non-interfering.

- In non-menopausal women: during the first half of the menstrual cycle, and ≥6 weeks after discontinuation of hormonal contraception (alternative contraception should be discussed).

- With concomitant serum potassium measurement, not for diagnosing PA but for interpreting aldosterone levels. If hypokalaemia is present and ARR is non-pathological, the test should be repeated after potassium correction.

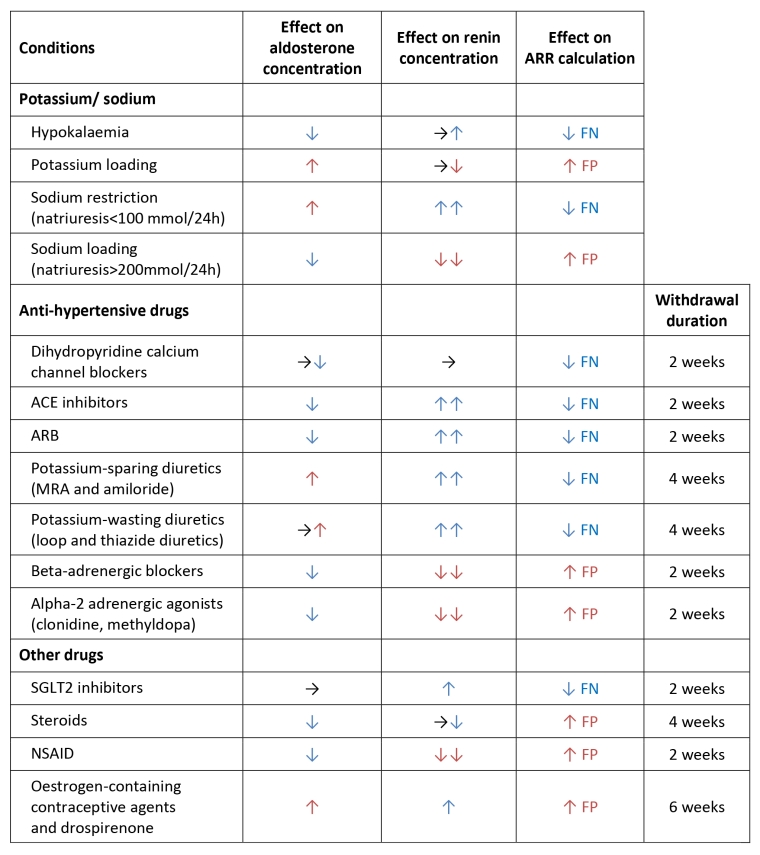

Table 2. Summary of the conditions and drugs that affect aldosterone, renin, and ARR.

ARR: aldosterone-to-renin ratio; FN: false negative; FP: false positive; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blockers; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; SGLT2: sodium/glucose cotransporter 2; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Special situations: when BP cannot be appropriately controlled without interfering anti-hypertensive medications

When aldosterone and renin measurements must be performed under interfering medications (Table 2), test interpretation should be entrusted to an expert familiar with the pharmacological impact on ARR values. Electrolytes (sodium and potassium) as well as multiple drug classes can alter renin, aldosterone, and thus the ARR calculation (Table 2).

A recent guideline recommends, in order to lower barriers to screening, performing the initial ARR test while the patient remains on their usual anti-hypertensive regimen. However, β-blockers should be discontinued whenever possible, as they commonly lead to false-positive results, and their withdrawal usually does not critically compromise BP control.

Practical approach when interfering treatments are present:

- If the first ARR suggests PA, repeat the test under a neutral treatment regimen to confirm the result.

- If the first ARR does not suggest PA but the patient has a high pre-test probability, repeat the test under a neutral regimen to avoid false negatives.

Confirmatory tests for the diagnosis of PA

Confirmatory testing is not required when the clinical and biochemical presentation is unequivocal, or when interfering treatments cannot be withdrawn (e.g., in cases of severe hypertension or high cardiovascular risk). These tests are useful when the initial screening does not yield a definitive conclusion, particularly in patients with a non-elevated aldosterone level despite a suggestive clinical context. Several confirmatory protocols have been described and reviewed [4]. In situations where diagnostic uncertainty persists, it may be appropriate to repeat the tests after 6–12 months, as hormonal profiles can evolve over time.

The role of adrenal computed tomography in the diagnosis of PA [4]

An adrenal computed tomography scan is performed after the hormonal diagnosis of PA in order to establish the underlying aetiology. Its primary objective is to exclude adrenocortical carcinoma, a rare but severe condition that must not be overlooked.

When an adrenal adenoma >1 cm is identified, a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test should be performed to rule out concomitant hypercortisolism.

A normal computed tomography scan does not exclude eligibility for surgery. Moreover, computed tomography is a mandatory prerequisite for adrenal vein sampling (AVS), exploring adrenal venous anatomy.

Although generally performed after biochemical confirmation, some clinicians advocate computed tomography as an initial step, particularly when hormonal or confirmatory tests are impractical or too complex.

Computed tomography may also incidentally reveal an adrenal mass (adrenal incidentaloma) during imaging performed for unrelated reasons (e.g., abdominal pain). In such cases, if the patient presents with hypertension and/or hypokalaemia, both PA and hypercortisolism should be investigated. Importantly, the term “adrenal incidentaloma” is inappropriate when the computed tomography scan is part of a hypertension work-up.

The role of AVS [4]

AVS is an indispensable tool in the management of PA, as it guides surgical decision-making by determining the side of aldosterone hypersecretion and thus the side of adrenalectomy in unilateral disease.

AVS is not required when the clinical, biological, and imaging presentation is strongly suggestive of unilateral secretion, i.e. in patients <35 years old, with severe hypertension and hypokalaemia, and with a unilateral adrenal nodule >1 cm associated with a thin contralateral gland. In such cases, surgery may be considered without AVS. In all other situations, AVS should be performed in patients with confirmed PA when surgical treatment is being considered. AVS is not indicated if surgery is contraindicated, not desired by the patient, or not indicated (mild PA with aldosterone <11 ng/dL [305 pmol/L] by immunoassay and normokalaemia).

AVS must be performed by a specialised multidisciplinary team, with expertise in both the technical procedure and the interpretation of results. The selectivity index validates interpretability of AVS and is defined by the ratio of cortisol concentration in the adrenal vein to that in the inferior vena cava. Selectivity is generally accepted if index >1.4–3 (commonly >2). The lateralisation index allows lateralised secretion to be distinguished from bilateral secretion, and is defined by the ratio of (aldosterone/cortisol) in the dominant side to (aldosterone/cortisol) in the contralateral side. Lateralisation index >4 validates lateralisation.

Positron emission tomography using 11C-metomidate could be a non-invasive alternative to AVS in the future. However, its availability remains limited, and larger prospective studies are needed before it can be integrated into routine practice [9].

The role of genetics [4]

Genetic testing should be considered in patients with PA who present with (i) an onset of the disease before the age of 20 years, (ii) a first-degree family history of PA, (iii) a family history of early-onset hypertension and/or stroke (<40 years)

Treatment of PA

The treatment for PA aims to control BP, normalise potassium levels, and reduce the elevated risk of cardiovascular complications associated with excess aldosterone [4,7]. The choice of therapy (medical versus surgical) depends on the subtype of PA (unilateral versus bilateral disease), the patient’s preferences, eligibility, and fitness for surgery [4,7].

Surgical treatment: unilateral adrenalectomy

Unilateral laparoscopic adrenalectomy is the treatment of choice for patients with documented unilateral PA who are eligible for or wish to undergo surgery [4,7].

Unilateral adrenalectomy provides substantial benefits.

- Normalisation of aldosterone and potassium levels occurs in nearly 100% of patients [7,9].

- BP decreases in 30–60% of patients, often with a reduction in anti-hypertensive medications. Hypertension is cured (BP <140/90 mmHg without medication) in approximately 50% of cases [7].

- Target organ damages are reduced, including albuminuria, left ventricular mass, and arterial stiffness [4,6,7].

- Surgery improves quality of life [7,8], reduces the occurrence of cardiovascular events (such as stroke and heart failure) and decreases all-cause mortality [4,7].

For patients with long life expectancy, surgery is a cost-effective long-term strategy [4,7].

Better postoperative outcomes are associated with young age, female gender, shorter duration of hypertension, higher number of anti-hypertensive drugs, and absence of vascular remodelling or chronic kidney disease [1,7,9].

Medical treatment

Medical treatment is indicated for patients with bilateral PA and for patients with unilateral PA who are not eligible for surgery, decline surgery, or when lateralisation status is unknown [4,7]. In patients with multiple comorbidities, who are not good candidates for surgery, and patients with mild PA, who typically have bilateral disease, AVS may be bypassed and medical treatment initiated directly [4,7].

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) are the first-line medical treatment. They effectively lower BP and normalise serum potassium levels [4,7]. They improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes [7].

MRA side effects are dose-dependent and may reduce treatment compliance [4,7]. They include gynaecomastia (up to 30% at 100 mg/day), erectile dysfunction, breast pain and Irregular menstruations [4,7].

Spironolactoneis the first-line MRA due to its low cost and wide availability [4,7].

Eplerenone is an alternative to spironolactone, particularly if the latter is not tolerated [7].

It is recommended to monitor renin levels. If hypertension is not controlled and renin is suppressed, it is suggested to increase the ARM dose to stimulate renin, which is associated with better prognosis [4,7]. It is advisable to titrate treatment to achieve an increase in renin relative to the baseline, rather than targeting an absolute level [4].

Dietary sodium restriction is recommended [7].

Epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) inhibitors (amiloride, triamterene) may be used as an alternative when MRA is not tolerated or as an adjunct when the target BP is not achieved [4,7].

Novel anti-aldosterone agents such as finerenone and baxdrostat are under investigation in PA with promising preliminary results [4,5,7].

Relative efficacy and decision factors

Although no randomised trials have directly compared long-term outcomes, observational studies indicate that medical therapy is less effective than surgery for long-term BP control and reduction in the number and dose of anti-hypertensive medications [4,7]. Medical treatment is also associated with a higher risk of stroke, heart failure, and all-cause mortality compared with surgical management [4,7].

Choosing between surgery and medical therapy should be guided by individual characteristics of the patient, their preferences (many favour surgery for the possibility of a definitive cure and improved quality of life), and access to specialised services such as AVS and adrenal surgery [4,7].

Conclusions/Impact on practice statement

Screening for PA, the most common cause of secondary hypertension, is strongly recommended in patients with resistant hypertension, hypokalaemia, adrenal incidentaloma ≥1 cm, and hypertension with disproportionate target organ damage.

The gold standard screening test is ARR, measured under controlled conditions. If ARR is obtained while the patient is on interfering drugs, expert interpretation is recommended.

Once PA is confirmed, an adrenal computed tomography scan is performed to exclude adrenocortical carcinoma.

For patients eligible for surgery, who prefer it, and with lateralised aldosterone secretion confirmed by AVS, unilateral adrenalectomy is the treatment of choice. In patients who are not surgical candidates or who decline surgery, spironolactone is recommended as first-line medical therapy.