List of abbreviations

BP: blood pressure

CV: cardiovascular

HF: heart failure

HFmrEF: heart failure with a midrange ejection fraction

HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

HTN: hypertension

Take-home messages

- HTN is the most prevalent risk factor for HF, particularly for HFpEF. Effective management of HTN significantly reduces the risk of developing HF, especially in the elderly.

- The relationship between BP levels and adverse CV outcomes in patients with HF is complex. Lower levels of systolic BP levels (<130 mmHg) are associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes, suggesting that excessive BP reduction may be detrimental in patients with HF.

- Optimal BP targets for patients with HF may vary depending on individual patient characteristics, including age, comorbidities and type of HF (HFrEF or HFpEF). Individualised treatment strategies are crucial to improving outcomes.

- New treatments, such as SGLT2 inhibitors and ARNi, show promise in reducing 24-hour BP, including nighttime HTN. The 2024 ESC guidelines recommend specific BP management strategies for patients with HF, highlighting the importance of individualised care and continuous monitoring.

- Nighttime BP and abnormal circadian patterns (e.g., non-dipping or riser patterns) are significant predictors of HF and CV events. Managing HTN at night is important to reduce the risk of HF and improve the prognosis.

Importance of understanding the relationship between HF and HTN

Heart failure (HF) and hypertension (HTN) have an indubitable relationship, regardless of form and variation. HF can present with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a midrange ejection fraction (HFmrEF), or a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). These three entities differ in their epidemiological profiles, presentation, and mechanisms. Compared to HFrEF, patients with HFpEF are older and more commonly have HTN and atrial fibrillation, while a history of myocardial infarction is less common. HFmrEF is an intermediate phenotype, with a prevalence of ischaemic heart disease similar to that of HFrEF, while other demographic characteristics, symptom profiles, comorbidities, laboratory values, and short-term outcomes are closer to those of HFpEF.

Although obesity, HTN, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and anaemia are among the numerous cardiovascular (CV) risk factors associated with HFpEF, HTN is the most prevalent. Arterial HTN has been reported to be the cause of HF in 64% of patients [1].

HF is a growing global epidemic with an estimated current prevalence of 38 million people worldwide. The prevalence of HF in developed countries is 1-3% of the adult population, increasing to 10% in people over 70 years of age. One in three people will develop HF after the age of 55. Generally, approximately one-half of patients with HF have HFpEF. The incidence and prevalence of HFpEF increases more with age compared to HFrEF, as observed in the Olmsted County cohort [2] and in the Framingham Heart Study [3]. Temporal trends in risk factors for HF, with a lower prevalence of ischaemic heart disease and increased HTN rates among those with HF, explain 75% of the shift toward a greater prevalence of HFpEF.

The incidence of HF varies between 3 and 29 per 1,000 person-years, reflecting differences in determination and adjustment between studies. In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, HF incidence rates varied by ethnicity [4]. This ethnic disparity was related to differences in the prevalence of HTN and diabetes.

Epidemiology of HTN and heart failure

HTN is the most prevalent risk factor for HF, with the highest population attributable risk among all risk factors. In the Framingham Heart Study cohort [3], HTN antedated the development of HF in 91% of subjects, while in the CV Health Study [5], the proportion was 82%. After adjustment for age and other risk factors for HF, HTN increased the risk of HF twofold in men and threefold in women. HTN accounts for 39% of cases of HF in men and 59% in women.

The lifetime risk of HF for people with blood pressure (BP) >160/90 mmHg is double that of those with BP <140/90 mmHg. An analysis of the CV Health Study and the Health ABC study in elderly individuals not receiving antihypertensive therapy has shown that the risk of incident HF at 10-year follow-up increases with increasing systolic BP, with subjects with blood pressure <120 mmHg having the lowest risk of HF.

However, 38% of all incident HF events occurred in subjects with systolic BP between 120 and 130 mmHg due to the higher proportion of elderly subjects in this group [6]. Several interventional studies have highlighted the importance of HTN control to decrease the risk of HF, especially in elderly subjects. Antihypertensive therapy reduced the risk of HF by 36 to 68% and had a greater impact on the prevention of HF than any other major CV outcome.

In the Systolic BP Intervention (SPRINT) trial, subjects at increased CV risk without diabetes or previous stroke and a baseline systolic BP >130/80 mmHg were associated with a 46% reduction in the risk of HF as well as a general decrease in the rates of CV death [7].

The absence of HTN, obesity, and diabetes prolongs HF-free survival. Subjects who are free of these risk factors at the age of 45 years have a risk of incident HF up to 85% lower, a longer survival without HF of more than 10 years, and live up to 13 years longer than those with all three risk factors.

HTN is the most prevalent risk factor, particularly for HFpEF. In high-income countries, the increase in the prevalence of HF is primarily due to ageing, while in low- and middle-income countries, the burden of HTN itself continues to increase and with it the subsequent danger of HF. Therefore, treatment of HTN significantly reduces the risk of HF, especially in the elderly (Table 1).

Table 1. Heart failure risk reduction by antihypertensive trials in subjects aged ≥60 years. Modified with permission from Springer Nature [8].

STOP-HTN

- Number of participants (N): 1,627

- Age range: 70–84

- Heart Failure (%): 51

SHEP

- Number of participants (N): 4,736

- Age range: >60

- Heart Failure (%): 55

Syst-Eur

- Number of participants (N): 4,695

- Age range: >60

- Heart Failure (%): 36

STONE

- Number of participants (N): 1,632

- Age range: 60–79

- Heart Failure (%): 68

Syst-China

- Number of participants (N): 2,394

- Age range: >60

- Heart Failure (%): 38

HYVET

- Number of participants (N): 3,845

- Age range: >80

- Heart Failure (%): 64

SPRINT

- Number of participants (N): 9,361

- Age range: 68

- Heart Failure (%): 38

HF: heart failure; HYVET: Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; SHEP: Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; STONE: Shanghai Trial of Nifedipine in the Elderly; STOP-HTN: Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension; Syst-China: Systolic Hypertension in China; Syst-Eur: Systolic Hypertension in Europe

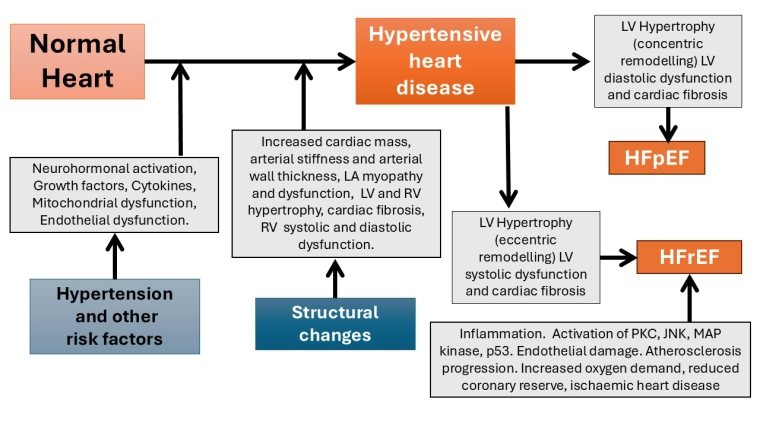

Figure 1. Progression from hypertension to heart failure.

Pathophysiology and diagnostics of hypertensive HF

HTN-related cardiac remodelling is a dynamic process with phenotypic transitions. Pressure overload leads to concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), characterised by increased cardiac mass at the expense of chamber volume. This condition results in diastolic dysfunction, reduced relaxation, and increased filling pressure, independent of the contractile function of the left ventricle (LV). This condition eventually leads to HFpEF, characterised by an increased LV mass with normal systolic function and symptoms of HF. HFpEF may evolve to HFrEF under certain circumstances, including poor control of BP and comorbidities. Risk factors such as older age, ethnicity, being overweight or obese, and concomitant diseases contribute to increased haemodynamic stress and the transition to different phenotypes of hypertensive cardiomyopathies and HF.

Messerli et al. have proposed four stages of HTN-related HF [9]:

- HTN without LVH;

- Asymptomatic HTN with LVH;

- Symptomatic HFpEF;

- Symptomatic HFrEF.

LVH is a cornerstone of the transition from HTN to HF. LVH is a condition characterised by increased cardiac myocyte size and myocardial fibrosis, which is associated with increased extracellular connective tissue and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) activity, activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) and protein kinase C (PKC) pathways, abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and apoptosis.

Neurohormonal dysfunction with overactivation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) plays a pivotal role in growth and hypertrophic signalling. Angiotensin II activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α and 1β (PGC-1α and PGC-1β) and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways, leading to stabilisation of the IкB kinase complex (IKK), activation of the nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and calcineurin and calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII), and hypertrophic gene expression. LV diastolic dysfunction with LVH is the key feature of HFpEF.

In addition to LVH and diastolic dysfunction, other pathophysiological processes are involved in the development of HF, such as increased vascular stiffness, systemic microvascular endothelial and capillary rarefaction, and pulmonary vascular disease. These conditions can play a central role in the clinical scenario with impaired LV preload recruitment due to excessive right heart congestion and blunted right ventricular systolic reserve [10] (Figure 1).

CV: cardiovascular; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle; MAP: mitogen-activated protein kinase; PKC: protein kinase C; RV: right ventricle

Although the diagnosis of hypertensive HF is based on traditional symptoms and signs of heart failure, the search for markers of left ventricular hypertrophy in HTN is an essential component in the treatment of hypertensive patients to prevent HF. Efficient BP control can partially reverse heart failure, even before the diagnosis of hypertensive heart failure. Echocardiography is the predominant technique for diagnosing LVH.

BP levels and CV outcomes in heart failure

The relationship between BP levels and adverse CV outcomes in patients with HF is complex and has been the subject of extensive research.

HTN contributes to structural and functional changes in the heart, such as left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction, which can eventually lead to HF. Optimal BP control is crucial to preventing the progression of HF and improving the prognosis in patients with established HF. However, the optimal BP targets for patients with HF remain uncertain, and studies show inconsistent results. Some studies suggest that higher BP levels are associated with better outcomes, while others indicate that elevated BP increases the risk of adverse events.

Recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort studies was published [11]. It was aimed at evaluating the associations between systolic BP and diastolic BP levels and adverse CV outcomes in patients with HF. The study included 43 unique observational cohort studies comprising 120,643 participants with HF. The outcomes of interest were adverse CV events and all-cause mortality. Pooled relative risks (RR) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for various BP thresholds.

The meta-analysis revealed several key findings:

- Systolic BP

- 140 mmHg vs <140 mmHg: No significant association with all-cause mortality (RR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.83-1.01), cardiovascular disease death (RR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.67-1.04), or hospitalisation for HF (RR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.80-1.21).

- 160 mmHg vs <160 mmHg: Associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality (RR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.62-0.74).

- <130 mmHg vs 130 mmHg: Increased risk of all-cause mortality (RR 1.15, 95% CI: 1.05-1.25) and hospitalisation for HF (RR 1.16, 95% CI: 1.06-1.26).

- <120 mmHg vs 120 mmHg **: Increased risk of all-cause mortality (RR 1.20, 95% CI: 1.01-1.42) and various CV endpoints.

- <110 mmHg vs 110 mmHg: Increased risk of all-cause mortality (RR 1.48, 95% CI: 1.17- 1.87) and adverse CV outcomes.

- Diastolic BP:

- 80 mmHg vs <80 mmHg: There was no significant association with all-cause mortality (RR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.61-0.10) or hospitalisation for HF (RR 0.92, 95% CI: 0.74-0.14).

- <70 mmHg vs 70 mmHg: There was no significant association with all-cause mortality (RR 1.09, 95% CI: 0.92-0.29) or hospitalisation with HF (RR 1.43, 95% CI: 0.82-1.55).

- Per 10 mmHg increase in diastolic BP: Associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality (RR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.81-0.87) and CV death (RR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.77-0.96).

The findings of this meta-analysis highlight the complex relationship between BP levels and adverse CV outcomes in patients with HF. In particular, lower and normal baseline systolic BP (SBP) levels (<130, <120, and <110 mmHg) were associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes, suggesting that overly aggressive BP lowering can be detrimental in patients with HF. On the contrary, higher levels of SBP (140 mmHg and 160 mmHg) were not associated with worse outcomes and, in some cases, were protective.

These results challenge the traditional approach of uniformly lowering BP in patients with HF and underscore the need for individualised treatment strategies. Optimal BP targets for patients with HF can vary based on individual patient characteristics, including age, comorbidities, and the presence of HFrEF or HFpEF.

These findings suggest that higher levels of SBP may be associated with better survival and that lower levels of SBP can increase the risk of adverse outcomes. These results emphasise the importance of individualised BP management in HF patients and highlight the need for further research to establish optimal BP goals. Healthcare providers should consider patient-specific factors when determining BP goals to optimise CV health and improve outcomes in HF patients.

Management of HTN in HF

HTN management is crucial for HF prevention, especially BP control, to prevent the progression of clinical HF. Antihypertensive treatment should focus on reducing BP rather than specific BP-lowering regimens. Calcium channel blockers (CCB) are inferior to other regimens for preventing HF, while diuretics are superior to other drug classes. The Trial of Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attacks (ALLHAT) found that thiazide-type diuretics were superior to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and CCB in preventing HF [12].

The 2024 ESC guidelines for the treatment of elevated BP and HTN [13] make the following recommendations for the management of HTN in HF. Individuals with symptomatic HF face an elevated risk of CV disease. Consequently, it is recommended that patients with confirmed baseline BP greater than 130/80 mmHg receive BP lowering therapy, with a target treatment goal of 120–129/70–79 mmHg, depending on treatment tolerance and out-of-office verification of BP after treatment. The recommendations are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Recommendations for the management of hypertension in HF. Reproduced with permission from Oxford University Press from [13]

Recommendations

- In patients with symptomatic HFrEF/HFmrEF, the following treatments with BP-lowering effects are recommended to improve outcomes:

- ACE inhibitors (or ARBs if ACE inhibitors are not tolerated) or ARNi

- Beta-blockers

- MRAs

- SGLT2 inhibitors

- Class: I

- Level: A

- In hypertensive patients with symptomatic HFpEF:

- SGLT2 inhibitors are recommended to improve outcomes in addition to their modest BP-lowering properties.

- Class: I

- Level: A

- In patients with symptomatic HFpEF who have BP above target:

- ARBs and/or MRAs may be considered to reduce heart failure hospitalisations and reduce BP.

- Class: IIb

- Level: B

ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin 2 receptor blockers ARNi: angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitors; BP: blood pressure; HFmrEF: heart failure with a midrange ejection fraction; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; MRA: mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; SGLT2: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor

It should be noted that numerous patients with systolic HF receiving optimal HF medications exhibit BP readings of <120/70 mmHg, and we do not advocate reducing their treatment unless it is justified by symptomatic adverse effects.

In addition to incorporating new information for angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitors (ARNi) and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor treatments, the 2024 HF recommendations remain broadly consistent with the previous guidelines and are summarised in the table.

Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers should be contraindicated in heart failure. Frailty and hypotension risk assessments are essential for elderly patients with HF who are evaluated for ARNi and SGLT2 inhibitor therapy, and these patients should be continuously monitored to confirm their tolerance to the drugs.

Nocturnal HTN and HF

Nighttime BP (BP) and abnormal circadian BP patterns such as non-dipping or riser patterns are significant predictors of HF and CV events. Studies have shown that higher BP at night and non-dipper/riser patterns are associated with increased risk of HF, independent of office BP. The JAMP study was the first to use the same ambulatory BP monitoring device and protocol at all sites, showing that higher values and a riser pattern of nighttime BP were significantly associated with the risk of developing HF [14].

LVH is a form of target organ damage that is more likely to precede non-ischaemic HF. It is linked to BP at night (BP), nocturnal HTN, abnormal BP dipping status, and increased risk of HF. The LV mass index is an independent risk factor for CV complications of HTN. Over the past two decades, evidence has shown that nighttime BP and the absence of a nighttime decrease in BP are important risk factors for the development of LVH.

The association between a non-dipper/riser pattern of nighttime BP and CV risk is primarily due to abnormal sodium handling by the kidney and dysfunctional nocturnal sympathovagal balance. Diuresis/natriuresis can contribute to the physiological variation of diurnal BP. A riser pattern of BP is associated with increased circulating volume, which is determined by salt sensitivity and salt intake. Evidence for this is provided by the fact that decreases in salt intake and treatment with diuretics reduce nighttime BP to a greater extent than daytime BP, shifting the circadian BP pattern from a non-dipper to a dipper profile.

New treatments for patients with HF, such as SGLT2i, ARNi, selective mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonists, and renal denervation (RDN) have the potential to reduce 24-hour BP, including nocturnal HTN. Treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes with SGLT2i significantly reduces the risk of hospitalisation for HF. RALES (Randomised Aldactone Evaluation Study) showed the benefit of MR antagonists in patients with HF. Antihypertensive treatment targeting nocturnal HTN is important components in achieving perfect 24-hour BP control [15].

Impact on practice

The intricate relationship between HTN and HF underscores the critical need for effective HTN management to prevent HF, particularly HFpEF. HTN is the most prevalent risk factor for HF, significantly increasing the risk of developing HF, especially in the elderly. The findings emphasise the importance of individualised BP management strategies, considering patient-specific factors such as age, comorbidities, and type of HF (HFrEF or HFpEF). In addition, managing nighttime HTN and abnormal circadian patterns is crucial to reducing the risk of HF and improving the prognosis. The integration of new treatments such as SGLT2 inhibitors and ARNi into clinical practice shows promise in reducing 24-hour BP, including nighttime HTN, thus enhancing CV outcomes. Healthcare providers should adopt these insights to optimise HTN management and prevent HF progression, improving patient care and outcomes.