What is eHealth?

eHealth is the use of information and communication technology to support health and health care. No individual cardiologist or clinical department can develop the appropriate expertise to tackle the numerous issues that surround eHealth. In response to these challenges the European Society of Cardiology decided to support cardiologists as they tackled these issues in day-to-day practice, establishing their own vision on this topic some years ago [1].

The major areas of Digital Health that have been impacted by the pandemic are telemedicine (we will focus on telecardiology), wearable sensors (we will focus on remote monitoring) and smartphone apps (as a link between telemedicine and wearables in many cases). All domains of eHealth have developed quickly in the past decade, with further acceleration during the COVID-19 crisis [2].

The current pandemic has shown the value of these technologies. Patients could not go to - or did not want to - visit caregivers, whether they were their general practitioners or hospitals. This caused a major change in hospital management where teleconsultations were rapidly introduced. It also forced confrontation with the problem, which had been under discussion for many years, namely that of reimbursement of teleconsultations. In many countries, health insurance now covers these costs, after seeing the need and the advantages of it [3].

Telecardiology something unknown?

With the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions on physical contact and lockdowns, many cardiovascular scientific associations and journals started to speak about telemedicine solutions [4]. However, many highlighted that no telemedicine programme (as in telecardiology) could be created overnight and, because of this, only the cardiology departments which had already implemented telemedical innovations could leverage them in response to COVID-19.

We already knew that telecardiology could be defined as “cardiology at a distance”. Another way to define this could be “the practice of cardiology without the usual cardiologist-patient physical consultation, via an interactive audio-video communications system”. However, unfortunately for us, even prior to the pandemic, it was well known that telecardiology did not have a successful track record, beginning with the early years of the twentieth century with Einthoven and his first electrocardiogram. Problems mentioned in 1984 by Higgins [5] were still present in 2020. 1) The initial expense in setting up telecardiology systems was high and it was difficult to justify the costs. 2) There was a resistance from many cardiologists who felt threatened by alternative approaches to the practice of medicine. 3) Reimbursement of cardiologists and legal implications still needed to be resolved.

Telecardiology before COVID-19

Cardiology clearly covered all the formats of telemedicine. We could certainly talk of telecardiology as something real in our daily practice but not really implemented. The current formats of telemedicine used in cardiology are:

A) Synchronous (live): remote consultations or teleconsultation, live video/audio

B) Asynchronous (store & forward): e-consultation, imaging documents, remote patient monitoring

In the field of cardiology there have been multiple experiences of telecardiology. Probably the main target was establishing a link with primary care through teleconsultation or e-consultation tools with different results.

Teleconsultation is not the Holy Grail; advantages, disadvantages, and limitations have been well described in the literature [6]. A summary of these elements are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Advantages, disadvantages and limitations of teleconsultation.

Adapted from [6] Barrios V, et al. Telemedicine consultation for the clinical cardiologists in the era of COVID-19: present and future. Consensus document of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2020;73:910-8. Copyright © 2020 Sociedad Española de Cardiología. Published by Elsevier España, S.L.U.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| They avoid exposure to contagion | Difficulty in correctly identifying the patient | Lack of legal coverage |

| Waiting list deadlines are shortened | Impossibility of physical examination | Lack of coverage by some liability insurance |

| They reduce the need for resources | Communication problems due to sensory deficits | Obtaining signature for informed consent |

| Greater ability to prioritise patients | Impossibility of complementary examinations | Difficulty expressing oneself due to lack of experience before a teleconsultation |

| They facilitate the organisation of care circuits | Loss of non-verbal communication | Lack of generalised access to video calls |

| Final healthcare costs reduced | Complexity on healthcare organisation, system disruption | Need of some eHealth literacy |

We must not forget that sometimes very complex strategies are not needed in order for telecardiology to offer improvements in cardiovascular outcomes. One of the best examples in the scientific literature was the Tobacco, Exercise and Diet Messages (TEXT ME) trial, whose strategy was simply based on reminder messages about healthy habits via the short text message service (SMS) for patients with proven coronary heart disease after discharge from hospital [7]. At 6 months, levels of LDL-cholesterol were significantly lower in intervention participants, with concurrent reductions in systolic blood pressure and body mass index, significant increases in physical activity, and a significant reduction in smoking. The majority reported the text messages to be useful, easy to understand, and appropriate in frequency

Remote monitoring - the great opportunity in eHealth

COVID-19 has changed the conversation about the value of remote monitoring, with increased focus on the benefits that come with less travel and inconvenience for patients and less social interaction. Perhaps achieving the same results as usual care is sufficient [8].

One great example of implementation of remote monitoring during COVID-19 in the telecardiology field is the TeleCheck-AF project (https://www.fibricheck.com/telecheck-af/). Maastricht Medical University Centre developed a mobile health (mHealth) intervention unit to support atrial fibrillation (AF) teleconsultations and guarantee the continuity of comprehensive AF management through teleconsultation during the pandemic.

TeleCheck-AF incorporated three important components: (i) a structured teleconsultation (“Tele”); (ii) an app-based on-demand heart rate and rhythm monitoring infrastructure (“Check”); and (iii) comprehensive AF management (“AF”). The on-demand heart rate and rhythm monitoring infrastructure is based on a CE-marked mobile phone app (www.fibricheck.com) using photoplethysmography (PPG) technology through the built-in camera allowing semi-continuous heart rate and rhythm monitoring of AF patients prior to and during the teleconsultation [9].

This strategy was extended to different European countries during the pandemic to the great satisfaction of physicians and patients as a recent publication has shown: the majority (>80%) of centres reported no problems during the implementation of the TeleCheck-AF approach and the recruited patients agreed that the app was easy to use (94%) [10].

Other examples of remote monitoring use during the COVID-19 pandemic published recently include:

- Virtual antiarrhythmic drug loading specifically with digital QTc electrocardiographic monitoring with the Kardia 6L mobile sensor (AliveCor Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) in conjunction with twice daily telemedicine video visits was feasible and safe during the pandemic [11].

- A study showed that the lockdown restrictions caused a marked decrease in healthcare use in France but not a significant change in the clinical status of heart failure patients under multiparametric remote monitoring [12].

- Functional capacity has been shown to be an excellent indication of current health status and a valid predictor of outcomes [13]; however, no reliable method for remote monitoring of functional capacity has been demonstrated. A comparative effectiveness study assessed the reliability and repeatability of a home-based 6-minute walking test (6MWT) with an Apple Watch compared to in-clinic 6MWTs in patients with cardiovascular disease during COVID-19, and showed that the results were reliable [14].

These approaches show that, despite different healthcare settings and mHealth experiences, an mHealth approach could be set up within an extremely short time and easily used in different European centres during COVID-19.

Changes in usual care during the pandemic. eHealth solutions.

One important point is that the current crisis with COVID-19 presented great challenges for many people facing quarantine and isolation. Not only has the crisis resulted in social and physical distancing from care providers, but healthcare services are also now provided in a different context using technology.

Paying attention to patients’ eHealth literacy is going to be key to improving health outcomes and lessening the impact of COVID-19 at both an individual and a societal level. Healthcare professionals will have to find ways to support patients who do not have advanced eHealth literacy skills to self-manage their own mental and physical health during COVID-19. By doing this, we could increase the possibilities of succeeding. eHealth literacy is a necessity in all modern technological societies [15].

Although the COVID-19 crisis has disrupted conventional cardiac rehabilitation programmes, it has also presented an opportunity to address cardiovascular (CV) health through remote and innovative means. The COVID-19 pandemic was an opportune time to show that patient-, physician- and system-related barriers to cardiac rehabilitation can be overcome by the large-scale deployment of digital health, with guidance already in place for implementation [16]. The home-based rehabilitation programmes have seen an important growth during the period of the pandemic. Many of them will probably remain after the crisis.

Even in heart failure management, a new impulse to monitoring and home follow-up was given. This involved offering clear recommendations on how to establish a successful programme of virtual visits through a great document provided by Heart Failure Association of America [17], specifically focused on the technology needed and how to perform a useful teleconsultation.

Lessons on eHealth from the COVID-19 period

The first lesson is that COVID-19 has unmasked many clinical visits as being unnecessary and perhaps even unwise. Telemedicine has surged, as we expected. Social proximity seems possible without physical proximity. Progress over the past two decades has been painfully slow towards regularising virtual care, self-care at home, and other web-based assets in payment, regulation, and training. The arrival of COVID-19 changed that in weeks. A good balance of virtual care to in person visits would release face-to-face time in clinical practice to be used for the patients who would truly benefit from it [18].

The second lesson is security in both directions (patient and physician). All the scientific societies in the field of cardiology went in the same direction, as Hollander proposed in the New England Journal of Medicine, adapted for this review: “A central strategy for health care surge control is “forward triage” — the sorting of patients before they arrive in the emergency department (ED). Direct-to-consumer (or on-demand) telemedicine, a 21st-century approach to forward triage that allows patients to be efficiently screened, is both patient-centred and conducive to self-quarantine, and it protects patients, clinicians, and the community from exposure. It can allow physicians and patients to communicate 24/7, using smartphones or webcam-enabled computers. Automated screening algorithms can be built into the intake process, and local epidemiologic information can be used to standardise screening and practice patterns across providers” [4].

The third lesson is that telecardiology is in some ways a return to the days of personal home visits. Elderly patients, those who have limited access to technology, or those with low eHealth literacy should be provided with tools and lessons in order to adapt. This will certainly be a tactic to help eliminate barriers and increase access. Telemedicine has the potential to make health care more personalised, efficient, and coordinated; it has the potential to improve efficiency, patient and clinician satisfaction, and health outcomes [19].

The fourth lesson is the great capacity for adaptation of the cardiovascular field. Many recommendations have been created in less than one or two months to help in the management of the pandemic. In many cases, telemedicine focused well on specific aspects of cardiology, such as the dynamic web pages created by the principal cardiovascular societies related to COVID-19 such as the European Society of Cardiology.

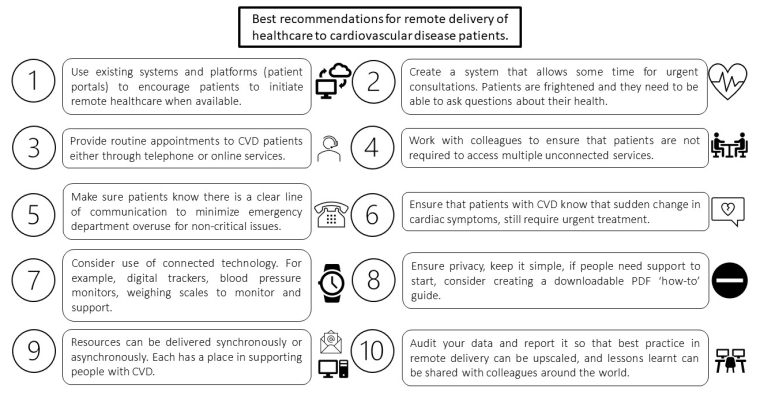

A good set of lessons always finishes with a summary. In this case, Figure 1 shows what could be the best recommendations for remote delivery of health care to cardiovascular disease (CVD) patients that we have learnt through the COVID-19 pandemic. People with CVD need to know that it is still very important that they seek appropriate health care if they experience sudden changes in their symptoms. For example, if a patient has chest pain, they should still call the emergency services. Although the “stay at home” message is vitally important, CVD emergencies will still occur. If people with CVD do not seek help in a timely fashion the consequences could be serious [20].

Figure 1. Best recommendations for remote delivery of health care to cardiovascular disease patients.

Adapted from Neubeck et al. Delivering healthcare remotely to cardiovascular patients during COVID-19: A rapid review of the evidence. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020 Aug;19(6):486-494. [20]. Copyright © The European Society of Cardiology 2020

CVD: cardiovascular disease

What could be the next improvements in telecardiology?

After COVID-19 we need to take the time to think about how to organise health care in the future. COVID infections have had a great influence on the functioning of eHealth, changing the way it is delivered and boosting its implementation in healthcare systems.

Professional medical societies have a pivotal role in promoting digital literacy, including the implementation of evidence-based digital redesign and innovation, and should act as conduits to meaningful engagement with other key stakeholders [8,15].

Some strategies for cardiology consultations which could be implemented in the future are based on the telemedicine tools acquired during COVID-19 are shown in Table 2 [6]. We have had previous satisfactory experiences with many of them. Their implementation would probably provide improved health care.

Table 2. Potential ways to reorganise cardiology consultations.

Adapted from [6] Barrios V, et al. Telemedicine consultation for the clinical cardiologists in the era of COVID-19: present and future. Consensus document of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2020;73:910-8. Copyright © 2020 Sociedad Española de Cardiología. Published by Elsevier España, S.L.U.

| First one-stop clinic |

|---|

| Have the echocardiograph available in the consultation: it can be used by the clinician or the imaging specialist who will centralise various consultations. The possibility to perform other tests such as the stress ultrasound should be available |

| Test results |

| Once the pertinent answers are received in the initial consultation, test results can be given over the telephone. Reports or images could be sent by email |

| Telephone follow-up |

| A face-to face consultation should be considered if there is any indication that a physical examination or complementary tests are necessary. This is an attractive option for conditions such as chronic coronary syndrome |

| Follow-up of heart failure |

| Promotion of self-monitoring, teleconsultations, video consultations, and sending of tables and spreadsheets via email or cloud-shared folders |

| Follow-up of arrhythmia patients |

| Promotion of self-monitoring through wearables, teleconsultations, and sending ECG tracings via email or cloud-shared folders |

| Link with the primary care physician |

| A multidisciplinary consultation can finally be carried out through simultaneous contact between the family physician and specialists in a conference call (with or without video) with the patient |

Conclusions

While eHealth and the telecardiology branch have been with us for a long time they have not been implemented properly. Telecardiology provides excellent opportunities: it allows patients to take a more active role in the healthcare system, facilitates patient-physician collaboration and communication, has the potential to make smart use of every byte of data, and shows promising results in different cardiovascular areas.

Obviously, the organisation of telecardiology is a challenge to our different health systems, especially in times of a pandemic, but it is also an opportunity for new solutions such as the TeleCheck-AF project. The usability, data accuracy and validation of the results obtained will need constant evaluation.

eHealth has certainly helped the medical world in managing this frightening new challenge, giving an opportunity to create safe environments in the worst phase of the crisis.

The scientific societies have an important role to play in leading telecardiology. We must be ready to overcome the resistance to change to a new cardiology practice which can have many potential benefits for all concerned.

Take-home messages

- Cardiology has clearly covered all the formats of eHealth including telemedicine. Telemedicine is not something new - it was well known from the beginning of the twentieth century.

- Teleconsultation is not the Holy Grail; advantages, disadvantages and limitations have been well described.

- Main lessons on eHealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: the unmasking of many clinical visits as being unnecessary, the safety of patients and physicians as being key, in some ways a return to the days of personal home visits, great capacity for adaptation of the cardiovascular field.

- TeleCheck-AF project during COVID-19 showed that eHealth experiences could be successful even during a pandemic.

- The cardiovascular scientific societies have an important role to play in leading eHealth implementation and helping to expand eHealth literacy skills.