Reviewed by Federica Ilardi

Why case fatality after AMI and HF is higher in non-urban areas

No patient should die because of where they live. This is the simple yet poignant take home message from the landmark meta-analysis by Faridi and collaborators, recently published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.1 The authors have been capable of synthesizing data from over 39 million individuals, eventually showing that living in a rural environment is associated with a significant increase in all-cause mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and heart failure (HF). These findings are quite striking in scale: rural patients face almost a 20% higher risk of dying for AMI and an 11% higher rate for HF compared to people living in towns and cities. While some methodological caveats should be borne in mind (e.g. the lack of analyses stemming from adjusted effect estimates and the issue of publication bias), this work is a strong call for action. Indeed, cardiovascular prevention and treatment have advanced markedly over the past two decades, but this meta-analysis reminds us that geography remains a powerful and persistent determinant of health outcomes, and ambience should be considered another key factor of primordial cardiovascular prevention.2

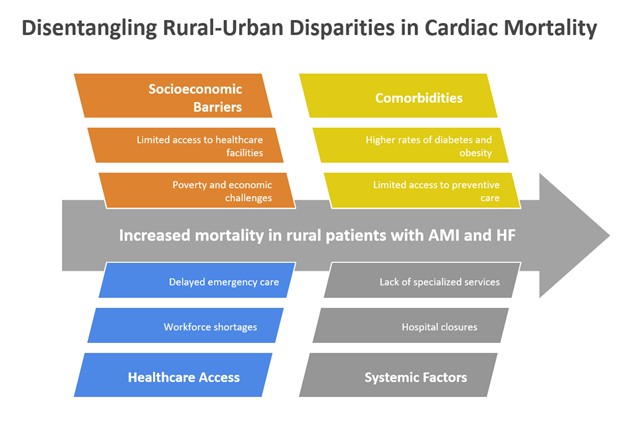

These compelling results beget an obvious question: why do rural patients fare so badly? The answer is as multifaceted as it is unsettling. First, reduced access to timely and specialized care - including emergency coronary angiography with ensuing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), multidisciplinary care, and structured follow-up—is a major contributor. Hospital closures, low-volume/expertise facilities, and workforce shortages further compound the problem.3 These healthcare system limitations also detrimentally interact with patient-level challenges such as greater distances to emergency services, lower health literacy, and higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors, including tobacco/alcohol use, physical inactivity, and unhealthy dietary regimens. Indeed, paradoxically people living in rural environments have often more adverse cardiovascular risk factor profiles than those living in urban areas.

These findings should not be viewed as inconsistent with our current understanding of the importance of the built environment, which plays an underappreciated but pivotal role in shaping cardiovascular risk and also outcomes.4 For instance, limited walkability, scarce recreational infrastructure, and reduced public transportation contribute to sedentary lifestyles and isolation, with environmental exposures adding additional layers of vulnerability, such as air pollution and heat stress. In addition, rural regions often lack the digital infrastructure required to benefit fully from telemedicine or remote monitoring, potentially widening rather than closing the care gap if digital solutions are deployed without strategic support.

Notwithstanding James Baldwin’s esthetics, disparities are not destiny. For instance, a universal healthcare system offers a unique opportunity to address these imbalances with targeted strategies: mobile cardiac units, rural health worker incentives, community-based screening programs, and the expansion of telecardiology—provided broadband access and digital literacy are addressed.5 Moreover, cardiovascular interventions could be modified and streamlined to make sure they end up being culturally appropriate, in partnership with the communities they aim to serve. Indeed, rural populations are not merely passive recipients of care but active partners in shaping sustainable health solutions, together with state-of-the art institutions.6

In conclusion, the systematic review and meta-analysis by Faridi and colleagues should be seen not as a verdict but as a call to action. Cardiovascular prevention must go beyond traditional models and engage meaningfully with geography, infrastructure, and inequality: I have primordial risk factors. While achieving cardiovascular justice will require bold public health investments, health system redesign, and persistent political will, the time has come to ensure that a patient’s zip code is not a proxy for their survival, because in cardiovascular medicine, as in society, distance should never equal disparity.

Figure 1. Key factors impacting on rural-urban disparities in cardiac mortality due to acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and heart failure (HF).

source: created by Giuseppe Biondi-Zoccai