Infective endocarditis (IE) is defined as infection of the endocardium. It concerns

principally the heart valves other structures' involvement (eg, the septum, chordae tendinae …etc) also falls into this category.

The management of IE is multidisciplinary and is comprised of cardiologists, intensive care physicians and cardiac surgeons. The 3 main pillars are:

- Antibiotic therapy : which should be adapted to the causative microorganism and continued for a sufficient period of time

- Intensive medical care : refers to treatment of the infective process and its

potential complications as well as cardiac supportive care - Surgery : has a threefold aim : a) eradicate the infective site, b) repair or treat the valvular lesions and c) prevent complications and recurrence of IE.

Indications for surgery in IE

The aim of surgery is to improve the survival of the patient and limit damage to the heart

valve. The timing of surgical procedures can be early (within 48 hours of antibiotic

therapy) or late (after 3 weeks of appropriate antibiotic and medical treatment).

Echocardiography (TTE and TEE) plays a key role in the decision making and follow up

of these patients. Consequently, surgery may be indicated for any of the following

reasons:

I. Hemodynamic indications

- Severe congestive heart failure with pulmonary edema. This is the most common indication for surgery. Early surgery for endocarditis of a native mitral or aortic

valve has soon to diminish the risk death in patients with severe left ventricular

insufficiency. Following surgery, mortality rate becomes comparable to that of

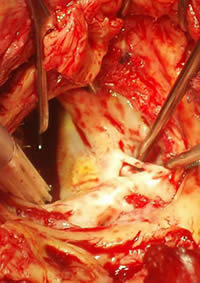

patients without co-existing heart failure1. - Massive valve regurgitation : mainly due to perforation of the valve (figure 1)

- Valve obstruction: by large vegetations

II. Embolic indications

Systemic embolisation is detected in approximately 37% of patients (21% of which are

asymptomatic). The decision to intervene surgically is taken on an individual basis and is dependant of the embolic risk. Most embolic events occur within the first 2 weeks. The indications of surgery in the presence of stroke are shown in table 1.The following

characteristics of the vegetation are considered high risk for embolisation and are

potential indications for surgical intervention2:

- Size >15mm

- Extreme mobility

- Causative microorganism: S bovis or S aureus

- Continuous increase in size despite adequate treatment

- Persistence after 2 weeks of adequate antibiotic therapy

Urgent surgery is indicated in the presence of a large mobile vegetation on the mitral valve especially if valve repair seems feasible. The appearance of mitral kissing

vegetation is another argument in favor of early surgery.

III. Bacteriologic criteria

- Progression of the lesion(s) despite adequate antibiotic therapy for at least 1 week

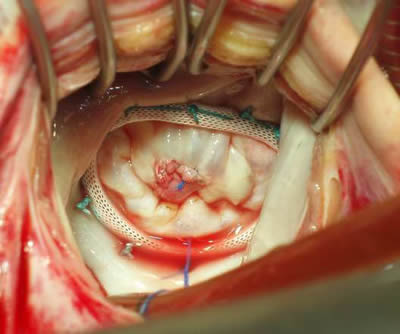

- 2. Persistent infectious processes not accessible to medical treatment (eg, abscess, false aneurysms, fistulae…) (figure 2).

- 3. Virulent causative microorganisms, e.g., staphylococci, Gram-negative bacilli,

fungi. - 4. Prosthetic valve endocarditis: these are associated with significant morbimortality

since there is the obvious risk of IE as well as that of a redo surgery. Surgical

intervention is considered early but indications are taken on the same basis.

Surgical procedures on the valves can be divided into 2 broad categories:

A. Valve repair or plasty: this is always preferred whenever possible. It is more

potentially applicable to the atrio-ventricular valves (mitral and tricuspid valves)

(figure 3). Early surgery has shown higher rates of valve repair and is associated

with better outcomes3.

B. Valve replacement: excision of a severe damaged valve can be the only surgical

option as is the case for prosthetic valve endocarditis.

In either case, all necrotic and infected tissue needs to be excised and sent for bacterial

culture, special culture and if necessary PCR. The defects need to be repaired:

Mitral valve repair can be performed in 2/3 of cases. This can be undertaken early after

the onset of the disease and before major tissue loss or destruction has occurred.

Homografts have supposedly greater resistance to infections compared to prosthetic

valves and their use is especially useful when aortic valve endocarditis is associated with

left ventricular outflow tract lesions. However, they are fraught with high early

calcification rates and the problems of availability. Translocation of the aortic valve can

be a useful alternative especially in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis4.

Table 1. Surgical considerations in the presence of stroke :

Symptom : Management

TIA with normal CT scan : Early surgery if high risk for repeat embolisation

&/or multiple emboli

Non hemorrhagic stroke : Unless surgery can be performed <72 hrs and CT

scan excludes cerebral hemorrhage, delay surgery

for 2-3 weeks (risk of complications with CPB)

Hemorrhagic stroke : Delay surgery for 3-4 weeks because of major

neurological risk

Coma : Contraindication to surgery since the prognosis is dependent on the neurological status of the patient

Figure 1. Large perforation of the anterior mitral valve with a large vegetation

Figure 2. Abscess of the aortic annulus

Figure 3. Repair of a perforation of the anterior mitral valve by pericardial patch.

Mitral annuloplasty was also performed.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.