Take-home messages [1]

- Both diabetes mellitus and peripheral artery disease (PAD) are coronary artery heart disease equivalents.

- Atypical presentations of PAD in diabetics are common.

- Computed tomography (CT) angiography is the preferred imaging modality to assess and plan intervention in PAD.

- Medical therapies include tight control of blood sugar, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia in addition to antiplatelet therapy.

- Invasive options include surgical bypass and endovascular therapies with similar limb rescue rates.

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is due to atherosclerotic narrowing and occlusion of the arteries [2]. Cardiovascular death is highly associated with its most severe form: chronic limb-threatening ischaemia. Both diabetes mellitus (DM) and PAD significantly increase the likelihood of vascular complications and amputation [3]. Patients with diabetes are more prone to develop PAD even in the absence of clinical coronary artery disease (CAD) [4].

Approach to PAD in DM

Individuals with diabetes mellitus have a 4-fold increase in incidence of PAD and mortality than non-diabetics [5-8]. Along with reduction in quality of life, they are at risk for disability and functional impairment [9,10]. Thus, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes advocates yearly screening in all diabetic patients irrespective of risk factors [11]. Notably, around 15% and 45% of diabetics have PAD within 10 years or 20 years respectively [12]. The presence of PAD may also trigger cardiac and cerebral events, thus optimal treatment can bring significant benefit and is mandatory in diabetics.

Estimates are that 75% of diabetics with PAD are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they are most commonly claudication or rest pain. Diabetes mellitus is present in around 30% of patients with claudication and 50% of patients with critical limb ischaemia (CLI) [13]. Moreover, individuals with DM and PAD are at a higher risk for infra-popliteal or tibial vessel disease and calcification with sparse collaterals than non-diabetics [14,15].

PAD in diabetics also manifests earlier and progresses more rapidly to CLI. Rest pain and claudication can go unrecognised in diabetics due to co-existing sensory neuropathy. Amputation rates are high in diabetics due to associated recurrent ulcers, comorbidities and end organ damage [16].

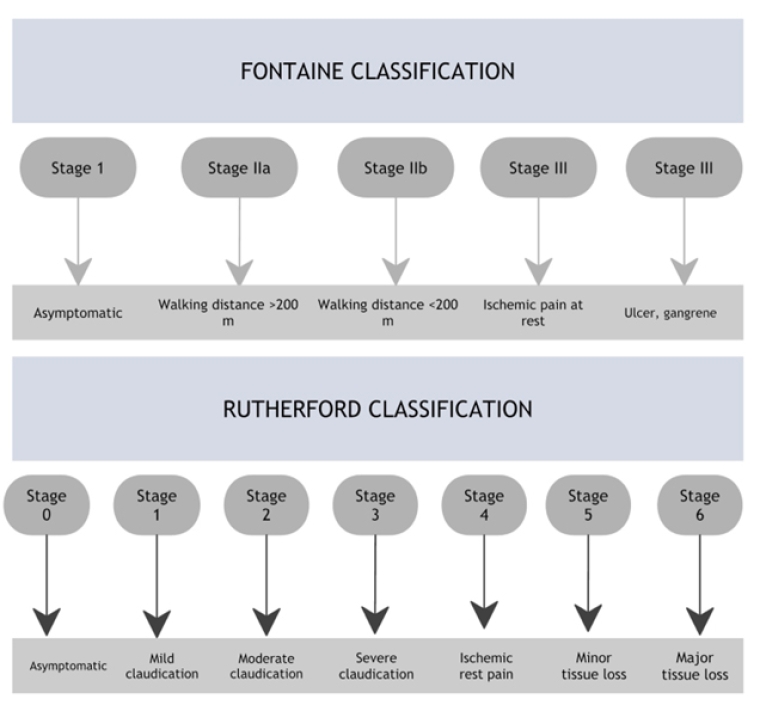

Figure 1. Peripheral arterial disease classification by Fontaine and Rutherford. [16]

Investigations for peripheral artery disease

1. Clinical examination to assess presence and intensity of peripheral pulses and capillary refill, skin colour, and temperature. Local foot ischaemia may be present despite normal foot pulses or normal toe pressure (e.g., heel lesion in diabetics who need dialysis). Thus, palpable pulses do not rule out the presence of PAD.

2. Doppler ultrasound: This can be used to determine Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI). An ABI value at rest below 0.9 and ABI >1.3 confirms PAD or medial sclerosis respectively. An ABI <0.7 or systolic ankle pressure <70 mmHg or systolic toe pressure <40 mmHg requires referral for revascularisation assessment. In CLI, both ankle and toe pressures are less than 50 mm and 30 mmHg, respectively. Attention should be paid to the fact that Doppler pressures are often falsely increased in diabetic patients.

3. Imaging studies: Ultrasonography, magnetic resonance (MR) angiography or computed tomography (CT) angiography are useful for symptomatic patients. Colour-coded duplex sonography helps to localise vascular lesions with its morphology. In doubtful cases, MR or CT angiography can be done. Prior to vascular grafting, intra-arterial angiography is required. The use of low or iso-osmolar contrast for angiography seldom causes contrast induced nephropathy in diabetics. Dehydration and nephrotoxic drugs must be avoided. Another alternative is CO2 angiography that can decrease contrast-induced nephropathy [16]. However, invasive investigations are, in most cases, only indicated when interventional treatment is planned.

Management of peripheral artery disease in diabetes mellitus

Therapy focuses on 2 factors: improving blood flow in symptomatic cases and treatment of vascular risk factors and comorbidities. Exercise training such as structured walking can be prescribed. Weight control must be advocated in overweight diabetics [16].

Both ESC and ACC guidelines [17,18] recommend smoking cessation, glycaemic control, blood pressure (BP) therapy and treatment with statins. The European guidelines further recommend therapeutic goals: low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels less than 70 mg/dl or >50% reduction from baseline, BP <140/90 mmHg. Both guidelines also suggest the use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors to reduce ischaemic events [19,20].

Maximum tolerable doses of statins must be prescribed in all confirmed cases of PAD (even in those without existing CAD) since this decreases mortality and amputation risk. Metformin is the oral hypoglycaemic drug of choice in concomitant DM and PAD. An SGLT-2 inhibitor or GLP-1 agonist can also be added. Safer SGLT-2 inhibitors are empagliflozin and dapagliflozin; canagliflozin should be avoided as it may increase the risk of amputation. Basal insulin analogues are safe to use [16].

Both U.S. and European guidelines advocate single antiplatelet therapy, either aspirin or clopidogrel, in symptomatic individuals. The U.S. guidelines recommend either aspirin or clopidogrel for reduction of coronary events whereas the European guidelines don’t favour antiplatelets in asymptomatic cases unless there are other indications such as CAD. Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), the use of both aspirin and clopidogrel, is only recommended for 1 month after percutaneous and surgical revascularisation by ESC guidelines (Class 1). At the same time, ACC guidelines give a Class IIb recommendation for long term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). Antiplatelets along with vorapaxar (thrombin receptor blocker) is only favoured by the U.S. guidelines (Class IIb recommendation). Although the ESC finds some benefit with vorapaxar, it does not make definite recommendations [21]. The European guidelines support antiplatelet therapy for patients who need anticoagulation for other indications. ACC also gives therapy with anticoagulants a Level III: harm recommendation.

Both guidelines put forward a Class IIa level recommendation for revascularisation in patients with intermittent severe claudication. These procedures are only recommended if guideline-directed therapy and structured exercises fail. These surgeries can help to raise functional status and life quality. While the U.S. guidelines disapprove of revascularisation procedures for avoidance of CLI, the European guidelines make no specific recommendations. Both groups, however, agree on endovascular approaches for persons with haemodynamically significant aorto-iliac disease and lifestyle-limiting claudication. For femoro-popliteal disease, the ACC guidelines opt for an endovascular approach while ESC favours such approach only for femoro-popliteal occlusions < 25 cm. However, both the ACC and ESC consent to surgical bypass for patients fit for surgery. Cases with a long superficial femoral artery lesion (>25 cm) and an available autologous vein received a special exemption according to the ESC guidelines. They further recommend endovascular revascularisation (Class IIb) in those unfit for surgery.

In CLI cases, both bodies opt for revascularisation. They also agree on the similar outcomes among endovascular and surgical approaches for revascularisation. Blood sugar control is a crucial factor to reduce limb loss, foot wounds and infection. Thus, both guidelines favour multidisciplinary wound care before and after revascularisation.

Acute limb ischaemia (ALI) requires emergency intervention. A “Pulse First” approach, where cases are classified based on the presence or absence of arterial and venous pulses is used by the ACC guidelines. The ESC however goes for early initiation of anticoagulation and then symptom assessment. Both favour early therapy with anticoagulants. Again, the U.S. opts for catheter-based thrombolysis then percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy or surgical thrombo-embolectomy. The European guidelines do not consider the superiority of thrombolysis over open surgical procedures [22].

Table 1. Differences between ESC and ACC guidelines on PAD. [22]

| Information |

ESC/ESVS guidelines |

ACCF/AHA guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| FOCUS | Focus on all non-coronary vascular disease | Focus on single disease location |

| AUDIENCE | Mainly cardiologists | All medical doctors |

| TREATMENT | For systemic atherosclerosis rather than PAD alone | Needs evidence specifically for PAD treatment |

| SELECTION OF EVIDENCE | Relegates small studies to Level of Evidence: C | Includes small, non-randomised studies |

| MEDICAL TREATMENT | Clopidogrel > aspirin to reduce cardiac events | Clopidogrel = aspirin to reduce cardiac events |

| SYMPTOMATIC TREATMENT | Does not promote cilostazol | Promotes cilostazol (Class I) |

| REVASCULARISATION | Emphasis on revascularisation and contemporary therapies | Emphasis on post-procedure surveillance and wound care |