Introduction

Cardiac tamponade is the most common cause of death in patients with acute type A aortic dissection (AADA) before they present for medical care [1,2]. Tamponade-induced hypotension associated with aortic rupture has been identified as a major risk factor for perioperative mortality in patients with AADA [3,4]. The presence of cardiac tamponade should prompt urgent aortic repair [5]. In this situation, percutaneous pericardiocentesis has usually been contraindicated, given the possibility that rapid and aggressive drainage of pericardial blood may precipitate a worsening leak from the aorta into the pericardium [6,7]. However, controversy surrounds the treatment of patients with haemopericardium and cardiac tamponade who will not survive until surgery.

Prevalence

Pericardial fluid collection is a frequent complication of AADA. Most commonly, the transudation of fluid across the thin wall of an adjacent false lumen into the pericardial space leads to a haemodynamically insignificant pericardial effusion, which is present in one third of patients [8]. The incidence of cardiac tamponade has been reported as being between 8% and 31% in patients with AADA [5, 8-12]. In addition, when cardiac tamponade occurs in patients with AADA, many die before reaching hospital and before a diagnosis is made [2].

Prognosis of cardiac tamponade due to aortic dissection

Recent studies have shown that surgical repair of an acute type A aortic dissection (AADA) has been markedly improved [13,14]. However, cardiac tamponade is one of the important risk factors in poor outcomes. Prolonged hypotension from admission to the operating room is associated with fatal outcomes in more than 40% of patients [5]. In-hospital mortality from AADA with cardiac tamponade was 54%, which was more than twice the mortality rate without cardiac tamponade (24.6%, p<0.0001) [10]. Therefore, the presence of cardiac tamponade should prompt urgent aortic repair [5].

Treatment of critical tamponade

Pericardiocentesis has been proven to be a safe and effective procedure in the treatment of cardiac tamponade caused by various underlying diseases [15]. However, in the case of cardiac tamponade in the context of AADA, the indications for pericardiocentesis are still a matter of controversy. In this situation, percutaneous pericardiocentesis has usually been contraindicated, given the possibility that rapid and aggressive drainage of pericardial blood may precipitate a worsening leak from the aorta into the pericardium. In 1994, Isselbacher et al reported the following catastrophic results: in six patients presenting with cardiac tamponade in the context of AADA on arrival at hospital or during emergency room evaluation, four underwent pericardiocentesis, three of whom died after pericardiocentesis [6]. As the remaining two patients, who did not undergo pericardiocentesis, survived, they speculated that pericardiocentesis induced intensified bleeding and extension of the dissection of the aorta [6]. They stated that blood pressure in four patients before pericardiocentesis was 90 mmHg to 130 mmHg, and blood pressure after pericardiocentesis was elevated to between 90 mmHg and 170 mmHg. The volume of aspirated fluids among the patients was 0 ml, 100 ml, 250 ml and 300 ml, respectively. The only patient to survive had a blood pressure reading after pericardiocentesis of 100/50 mmHg. Pericardiocentesis had been attempted unsuccessfully, and the patient then underwent successful surgical repair of the dissection. Therefore, the authors postulated that cardiac tamponade might have a role to play in minimising the progression of aortic dissection by lowering blood pressure and reducing the cardiac ejection function. Elevated blood pressure and the dislodging of a thrombus from the pericardial space during pericardiocentesis might cause a closed communication to reopen [6]. Based on this report, in its 2001 guidelines, the European Society of Cardiology cautioned against pericardiocentesis as a therapeutic step before surgery for patients with cardiac tamponade in the context of aortic dissection (class III) [7].

However, according to 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease, pericardiocentesis can be performed by withdrawing just enough fluid to restore perfusion in patients with haemopericardium and cardiac tamponade who cannot survive until surgery [8]. In addition, cardiac tamponade is a considerable risk when anaesthesia is induced, as preload reduction by anaesthetic agents may precipitate electromechanical dissociation [16].

The failure of the pericardiocentesis in Isselbacher’s study might have been caused by excessive high pressure, which causes rupture or greater extension of the dissection not only by open communication. Indeed, several recent studies have suggested that preoperative pericardial drainage may be an effective temporising strategy in selected patients with acute type A aortic dissection complicated by critical cardiac tamponade [16-18].

Hayashi et al reported that controlled pericardial drainage (CPD) procedures provided a better outcome compared with Isselbacher’s study [16]. This is because the indication of pericardiocentesis was from patients who displayed hypotension after intravenous fluid resuscitation, and with an average systolic blood pressure before drainage of 64.3 mmHg – which was lower than that cited in Isselbacher’s study [6]. Drainage of pericardial effusion cited in the study was more finely controlled, and the total volume of fluids that were aspirated was approximately 40 ml [16]. That included 10 of the 18 patients, who required a volume of aspiration of only 30 ml or less and a minimum volume of aspiration of 10 ml – again, much smaller than those in Isselbacher’s study [6]. As a result, the elevation of systolic blood pressure was about 30 mmHg [16]. In addition, systolic blood pressure after drainage was around 95 mmHg in their patients, and was achieved without inducing fatal bleeding from the aorta [16]. Based on this report, 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases recommended pericardiocentesis in the setting of aortic dissection with haemopericardium, with the recommendation that controlled pericardial drainage of very small amounts of the haemopericardium be carried out to stabilise the patient temporarily in order to maintain blood pressure at about 90 mmHg (class IIa) [19].

Kimura et al reported a clinical series of 351 patients of acute type A aortic dissection, including eight patients who underwent preoperative pericardiocentesis: seven patients survived and one died. They commented that careful pericardiocentesis could be a useful treatment option for cardiac tamponade [17]. Cruz et al reported a similar drainage approach in six patients and suggested that pericardiocentesis can be carried out safely in selected patients if performed in a controlled way, i.e., draining small volumes that are just enough to restore circulation, while closely monitoring changes in blood pressure to avoid excessive elevation [18]. Table 1 presents a summary of previously published case series as well as statements included in the guidelines regarding pericardiocentesis in critical cardiac tamponade with aortic dissection. Importantly, controlled pericardiocentesis should not be seen as a definite treatment. Emergency surgical intervention is required for patient survival.

Table 1. Summary of previously published case series and statements in the guidelines regarding pericardiocentesis in critical cardiac tamponade with aortic dissection.

Isselbacher et al (1994):

- Series of 10 patients with cardiac tamponade in the context of proximal aortic dissection:

- in five patients, pericardiocentesis was performed before surgery – three patients died and two survived.

- Reference 6

Erbel et al (2001):

- The ESC guideline cautioned against pericardiocentesis as a therapeutic step before surgery for patients with cardiac tamponade in the context of aortic dissection (class III).

- Reference 7

Hiratzka et al (2010):

- The ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines stated pericardiocentesis can be performed by withdrawing just enough fluid to restore perfusion in patients with cardiac tamponade who cannot survive until surgery.

- Reference 8

Hayashi et al (2012):

- Series of 18 patients with cardiac tamponade not responsive to fluid resuscitation in whom finely controlled pericardial drainage was successfully performed while waiting for aortic surgery.

- Reference 16

Kimura et al (2014):

- Series of 351 patients of acute type-A aortic dissection.

- Eight patients with critical cardiac tamponade underwent preoperative pericardiocentesis – seven patients survived and one died.

- Reference 17

Cruz et al (2015):

- Series of 21 patients of acute type-A aortic dissection in a centre without cardiovascular surgery.

- Six patients underwent controlled pericardiocentesis for cardiac tamponade – five patients improved and were transferred to the operating room, and one died.

- Reference 18

Adler et al (2015):

- The ESC guidelines recommended that controlled pericardial drainage should be considered to stabilise the patient temporarily in the setting of aortic dissection with haemopericardium (class IIa).

- Reference 19

Controlled pericardial drainage (CPD)

Procedure

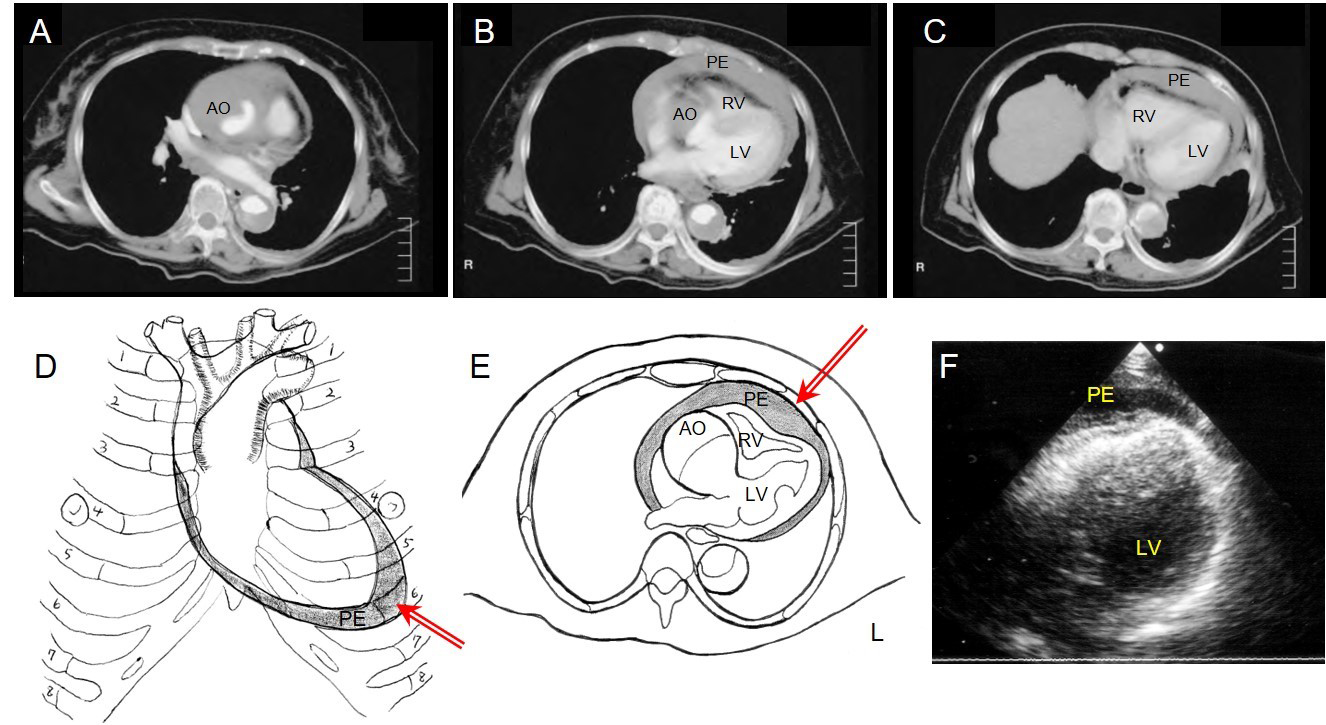

Hayashi et al offered detailed descriptions of their procedure. With the patients in a prone position and under local anaesthesia, an 8 Fr pigtail drainage catheter with multiple side holes was inserted into the pericardial space (PS) under ultrasound guidance [16]. In acute cardiac tamponade caused by AADA, additional pericardial effusion (PE) accumulated around the apex of the heart rather than just above the diaphragm (Figure 1D). Usually, PE was thickest just beneath the skin of the 4th or 5th intercostal space and on or just inside the left mid-clavicular line. Before CPD, the thickest point was marked up on the skin using echocardiography (Figure 1F). As described in Figure 1, puncture was performed from the marked-up point at a 90° angle to the skin, with the needle carefully advanced vertically to the PS. Within 3.0 cm from the skin, the point of the needle was able to penetrate the PS. To avoid complications such as laceration of the coronary artery, vein, or myocardium, the PE needs to be greater than 10 mm in thickness, and the needle should be inserted meticulously. If the needle is advanced laterally, it could cause injury to the lung and pneumothorax. This procedure took 5.3±1.8 minutes. Aspiration of the PE started after the catheter had been placed into the PS. At the beginning, 5 ml to 10 ml of haemopericardium was aspirated and changes in blood pressure were closely observed to prevent excessive elevation of blood pressure. The drainage volume was controlled through intermittent aspiration, using a 10 ml syringe and 5 to 10 ml of aspiration each time, to maintain systolic blood pressure at around 80 to 90 mmHg. After CPD was performed and circulation was restored, the patients were transferred to the operating room to undergo immediate aortic repair. The time interval between CPD and surgery was 58.2±25.0 minutes [16].

Figure 1. Controlled pericardial drainage for critical cardiac tamponade with acute type A aortic dissection.

A), B) & C) Thoracic computed tomography of patient 1 demonstrates AADA with massive pericardial effusion with compression of the right ventricle.

D) Schematic illustration demonstrates accumulation of the pericardial effusion of AADA in a prone position, and the red arrow shows the point and direction of the CPD.

E) Schema demonstrates AADA with massive pericardial effusion and the red arrow shows the angle of the puncture is 90° to the skin.

F) Ultrasound findings from the 5th costal space show pericardial effusion just beneath the skin.

PE: pericardial effusion; AO: aorta; LV: left ventricle; RV: right ventricle

CPD can be performed safely and applied promptly in the emergency room while the patient is awaiting surgery. Importantly, CPD has a closed drainage system through an indwelling 8 Fr pigtail catheter, so the volume of aspirated fluids can be easily controlled to the closest millilitre, while attention must be paid to ensure that blood pressure does not rise too high [16]. A few precautions must be taken during CPD treatment. In all cases, the catheter is inserted percutaneously from either the 4th or the 5th intercostal space and on the left mid-clavicular line under ultrasound guidance. Care must be taken to avoid pneumothorax, injury to the heart and coronary vessels, or the insertion of the catheter into the clot. Ultrasound guidance is quite effective in allowing us to place the catheter into the target space precisely.

Mechanisms of action

From the aspect of physiological changes produced by tamponade, the amount of aspirated blood should be small enough to stabilise circulation of critical cardiac tamponade. The normal pericardial space has a steep pressure-volume curve [20]. Rapidly increasing pericardial fluid first reaches the limit of the pericardial reserve volume, and then quickly exceeds the limit of parietal pericardial stretch, causing a steep rise in pressure. This becomes even steeper as smaller increments in fluid cause a disproportionate increase in pericardial pressure [20]. The end result of an increase in pericardial pressure is an impediment caused by the diastolic filling of the ventricles, resulting in a precipitous decrease in cardiac output and arterial blood pressure, and haemodynamic collapse [14]. Therefore, draining a small volume of fluid in the pericardial space results in a drastic decrease in pericardial pressure and in rapid clinical and haemodynamic improvement [16].

Even when blood pressure cannot be elevated after massive intravenous volume infusion, and the patient may not survive until reaching the operating room, an attempt to resuscitate the patient with pericardiocentesis in a controlled way is warranted and might indeed be successful [16-19]. However, in cases of an acute accumulation of the haemopericardium from rupture of the false lumen, CPD will not improve the circulation because of the drainage tube’s small diameter. In such cases, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is mandated, and open pericardial drainage from the subxyphoidal approach must be attempted if pulseless electrical activity continues before emergency mobilisation to the operating room for aortic repair [16].

Conclusions

Cardiac tamponade is associated with fatal outcomes in patients with type A aortic dissection, and is considered an important risk factor. Controlled pericardial drainage should be one of the treatment options to reduce haemodynamic instability in patients with cardiac tamponade that complicates AADA. An improvement in the patient’s preoperative state may lead to improved outcomes of AADA with cardiac tamponade.