Background

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most commonly acquired valvular heart disease in the Western world. Mortality for untreated symptomatic severe AS in high-risk patients reaches 50-60% at 2 years (1) and surgical aortic valve replacement is currently the gold-standard. However, established standard of care is now transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in 1) inoperable patients or 2) aortic stenosis patients at high risk for increased operative complications and death (2, 3, 4).

Both currently available prostheses offer hemodynamic performance comparable to surgical heart valves in terms of transvalvular gradient as well as effectiveness of the orifice area. Patients enjoy improved symptoms and left ventricular function. Furthermore, there has been no reported case of late valve failure in the 6 years of follow-up we have with TAVI and newer devices (SAPIEN XT and CoreValve) from in vitro testing indicate an anticipated durability in excess of 10 years (5).

TAVI requirements

Nevertheless, success with TAVI requires:

- Appropriate screening

- Patient selection based on careful analysis of cardiovascular anatomy and clinical criteria

- Involvement of a multidisciplinary team

- Full delineation of the anatomy of the aortic valve, aorta, and peripheral vasculature through evaluation and use of multiple imaging modalities

- Echocardiography - critical in the assessment of candidates for TAVI, it provides much needed anatomic and hemodynamic information such that the European Association of Echocardiography in partnership with the American Society of Echocardiography have developed recommendations for the use of echocardiography in new transcatheter interventions for valvular heart disease (6).

Left ventricular diastolic performance during TAVI

We published a recent study showing improvement in diastolic function parameters immediately following successful TAVI. Sixty-one patients with severe AS and preserved LV systolic function with LV diastolic dysfunction received successful TAVI. Patients had and a decrease in LV end-diastolic pressure. Those with a restrictive pattern immediately after TAVI presented a smaller decrease in LV end-diastolic pressure than those with grade I or II diastolic dysfunction. This was the first study describing LV diastolic performance during TAVI. These results explain the remarkable clinical improvements in heart failure symptoms reported shortly after TAVI (7).

Prosthesis-patient mismatch

On the other hand, several studies examining the clinical and hemodynamic impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch (PPM) in patients undergoing TAVI, found that PPM can be observed after TAVI and may be accompanied by less favorable changes in transvalvular hemodynamics, as well as limitation of left ventricular (LV) regression, persistently elevated LV filling pressure, and lower clinical functional status improvement (8).

Paravalvular regurgitation

Valvular aortic regurgitation (AR) is uncommon with current transcatheter valves however paravalvular regurgitation due to incomplete annular sealing is prevalent. Paravalvular AR appears to be minor in most patients however the hemodynamic impact and effect on cardiac chamber remodeling is unkwown, and there have been findings of hemodynamic deterioration, left ventricular remodeling or hemolysis in certain patients. As a result, accurate evaluation and detailed description of AR after TAVI are essential for follow-up. Presence of significant post procedural AR (defined as ≥2/4) has been described as a strong independent predictor of in-hospital death following TAVI (9).

- 3D TTE better correlated with AR volume superior in the evaluation of paravalvular prosthetic regurgitation, than 2D TEE. No data yet regarding the evaluation of aortic paravalvular leaks

Up to now, no systematic methodology has been offered to assess severity of AR. Vena contracta width measured using 2D TTE is one of the most robust methods to assess AR in native valves and is well correlated with regurgitant orifice area but in presence of prosthesis, assessment using 2D TTE might be difficult.

We included 72 patients undergoing TAVI in a recent study to describe the position and severity of paravalvular AR jets using 2D and 3D TTE. A model was designed for systematic paravalvular AR location description. Vena contracta width was measured using 2D TTE views and planimetry of the vena contracta was assessed once perfect alignment plane had been obtained using the multiplanar 3D transthoracic echocardiographic reconstruction tool. Aortic regurgitation volume was calculated as the difference between 3D- TTE derived total left ventricular stroke volume and right ventricular stroke volume estimated using 2D TTE.

Using AR volume for accurate classification of AR severity, 57,4% of patients demonstrated AR; 13,3% had central AR and 44% had paravalvular jets. The paravalvular region from 12 to 3 o’clock was the most common location for mild as well as for moderate paravalvular AR jets, but no correlation with aortic valve calcification severity or asymmetry was found. Vena contracta widths were similar among patients with moderate and mild AR but vena contracta planimetry was larger in patients with moderate AR than in those with mild AR. Vena contracta planimetry on 3D TTE was better correlated with AR volume than vena contracta width on 2D TTE. Moreover, 3D TEE was observed to be superior to 2D TEE in the evaluation of paravalvular prosthetic regurgitation, providing more information regarding location and a more accurate estimate of aortic and mitral valve prosthetic paravalvular defect size.

Regarding evaluation of aortic paravalvular leaks using 3D TTE however, no data has yet been presented nor regarding the assessment of clinical benefit of 3D TTE for long-term follow up (9).

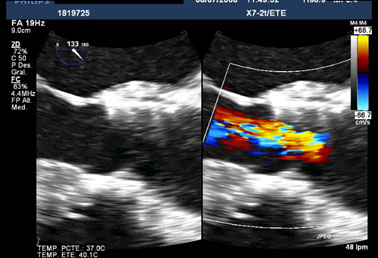

Figure 1. Two-dimensional transoesophageal echocardiography image of a transcatheter valve associated with central aortic regurgitation.

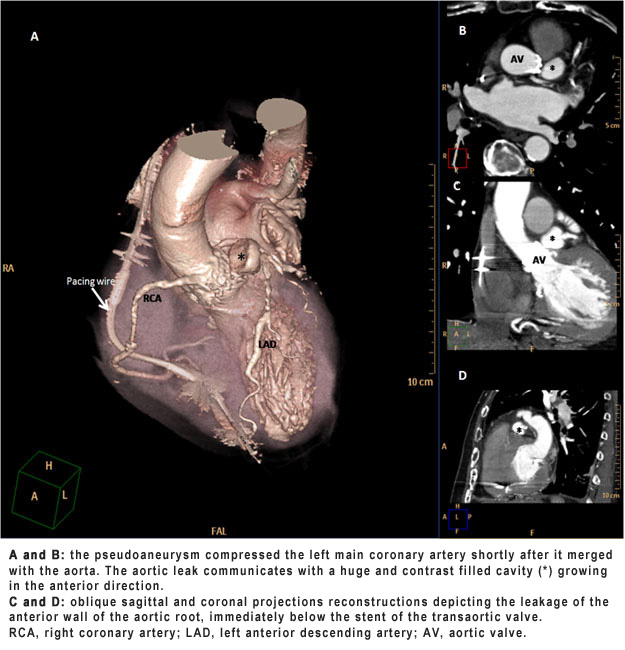

Figure 2. Computed tomography angiography of aortic root and ascending aorta. (click on image to enlarge)

Conclusion:

The new ESC guidelines of valvular heart disease are about to come forth, and it is expected that TAVI in the future will be tested in less complex patient populations and that it will enter into competition with surgical aortic valve replacement. Indeed, an important paradigm shift toward the selection of lower surgical risk patients for TAVI should lead to better clinical outcomes in lower than in higher surgical risk patients undergoing TAVI (10). Proper selection of candidates and close follow-up using imaging modalities will play an important role in new procedures.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.