Although European countries have various protocols and policies regarding the decision-making process for clearing patients for their return to work following an acute coronary event, a brief description of the Spanish policy on that topic will be of interest to many readers.

1) Economic considerations

Cardiologists are frequently required to give their judgment about the cardiovascular status of patients recovering from acute coronary syndrome. However, rather frequently in our scenario, specialists may easily take a passive, disinterested and even permissive position on the matter. Although the wellness of their patients is their first concern, cardiologists must also consider other factors. We belong to society and must cope with a socio-sanitary system for which sick leaves is rather expensive: nearly 16.000 € per patient on sick leave for six months; multiply this amount by the 17.000 anual infarctions in the working age population, the bill adds up to 285 million € each year. In this context, part of the responsibility that patients return to work as soon and in the best conditions possible fall on doctors in charge of judging their cardiac sequelae (1).

2) Role of cardiologists

It is not the cardiologist’s job to decide whether a patient can return to work or not, there are specialised doctors whose duty it is to do so. Many factors related to the almost infinite peculiarities of job positions, to considerations such as age, motivation, satisfaction with previous position, salary, trade, unemployment rates, comorbidity, or even economic aspects - which in some studies have shown influential on return to work than clinical endpoints - are involved in that decision (2, 3). Evaluation by a cardiologist of the sequelae and functional status of the patient is irreplaceable however she or he is not asked to precisely state when and in which conditions a particular patient can (or should not) return to work. Nevertheless, the cardiologist surely has to deliver information regarding the patient’s functional capacity to work and the possible risks a patient runs if cleared for work return.

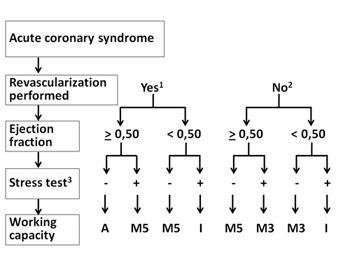

3) Cardiac parameters to be measured: our personal strategy in a simple algorithm

Regarding the patient’s functional capacity to work and the possible risks a patient runs if cleared for work return, we have summarised our personal strategy in a simple algorithm, depicted in figure 1. It has not been validated nor published to date and it is only intended to be approximate and useful for practical purposes. Obviously it is impossible to cover all cases. Only patients without obvious arrhythmia (ventricular ectopy, atrial fibrillation) are included. Furthermore, only the physical component of work is covered, leaving out other aspects that could also be important in certain contexts (day/night shift, location, position, environment, “stress”, risks for third party) and should remain the responsibility of occupational health doctors. Variables included are well known and easily obtained by non invasive tests routinely performed in an outpatient basis: if revascularisation was performed or not, left ventricular ejection fraction on the echocardiogram and clinical and electrocardiographic results of a symptom-limited effort test. With those results it should be straightforward to provide a thorough expert report highlighting the sequelae and functional capacity for return to work.

4) Timing

Lastly, an important aspect to be considered as well is regarding when return to work is advisable. Traditionally, return to work was advised within a wide timeframe, between 3 and 6 months after an acute coronary event or a coronary bypass surgery (4, 5). This recommendation is now obsolete as it does not take into account the important improvements in acute therapies, preventive treatments and cardiac rehabilitation that have occurred in recent years. Modern guidelines have shortened this period to 1-3 months, but are not fully clear in this respect (6).

Fig. 1: Algorithm for cardiac assessment in order to clear coronary patients for return to work.

Figure legends:

1- Complete or clinically meaningful, be it percutaneous or surgical

2- Revascularisation not performed, suboptimal or not suitable by clinical or anatomical criteria

3- It is important to perform a symptom-limited stress test; defined as negative if no clinical or electrocardiographic abnormalities (ST depression > 1 mm or ventricular arrhythmias) arise at > 7 METs

A- Cleared for any type of work

M5- Can perform tasks requiring < 5 METs

M3- Can perform tasks requiring < 3 METs

I- Not suitable for any type of work

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.