Introduction

The understanding of the genetic background of cardiomyopathies and their potential role in predisposing to myocarditis has significantly increased in recent years. Inflammation is now recognized as both a trigger and a component of the pathophysiology of several inherited myocardial diseases, and myocarditis may represent the first clinical manifestation of an underlying cardiomyopathy.

The 2025 ESC Guidelines on Myocarditis and Pericarditis recommend genetic testing in patients presenting with acute myocarditis associated with arrhythmic events, recurrent episodes, or imaging findings suggestive of an inherited substrate, underscoring the growing importance of genomics in this setting.

Here, we report a clinical case of myocarditis with surprising end genetic diagnosis in her and her family.

Case Presentation

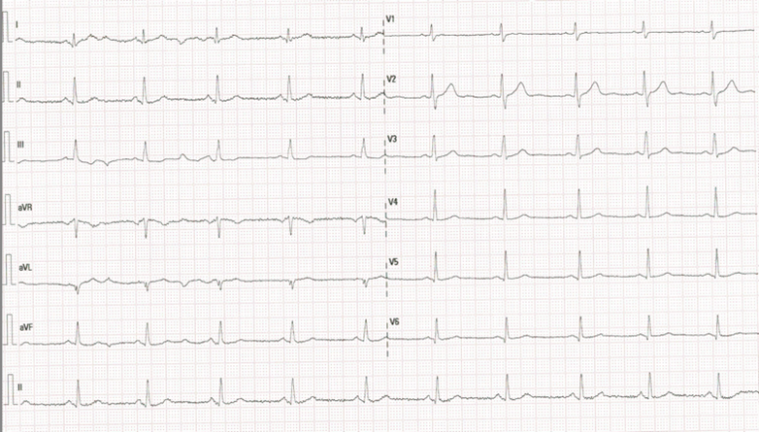

A 39-year-old woman with no family history or cardiovascular risk factors and a history of sacroiliitis presented to the emergency department with sudden-onset, oppressive chest pain radiating to the left arm. The pain was constant and only partially relieved by rest. At her primary care center, an initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm without ST-segment abnormalities (Figure 1), and she referral to hospital. On arrival, the patient remained mildly symptomatic. Vital signs were stable, and physical examination was unremarkable. Repeat ECG showed no ischemic changes, but laboratory testing revealed a marked elevation of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (peak 2253 ng/L, upper limit of normal <20 ng/L). Creatine kinase was 399 U/L (normal < 200 U/L), LDH 141 U/L (normal <180), and C-reactive protein mildly elevated. Basic metabolic profile and complete blood count were within normal limits.

Figure 1 Sinus rhythm 70 bpm, normal electrical axis, and a narrow QRS complex with normal ST-segment and T-wave morphology.

A transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated mild inferolateral hypokinesia with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, and a mild pericardial effusion, consistent with suspected diagnoses of acute myopericarditis. Coronary angiography showed normal epicardial coronary arteries. During early monitoring, she experienced a 10-beat non-sustained ventricular tachycardia that resolved spontaneously. Bisoprolol was initiated with good tolerance.

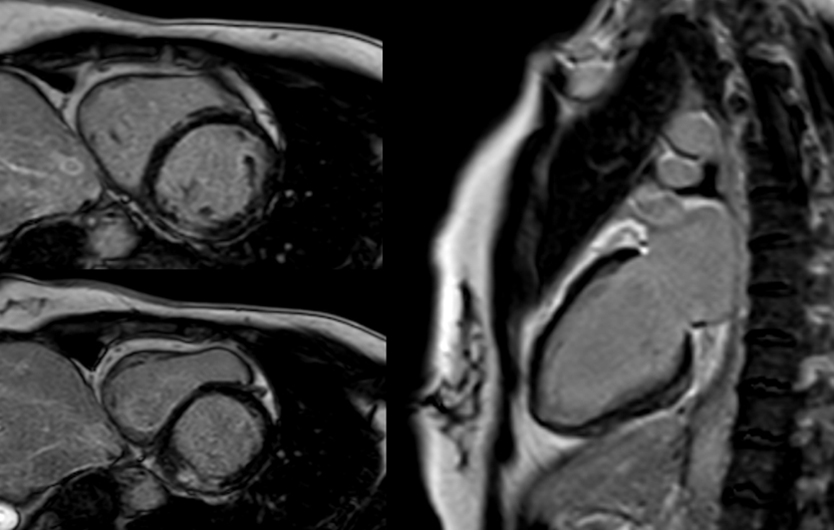

A cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) performed on day 6 revealed a non-dilated, non-hypertrophic left ventricle with mildly reduced systolic function (LVEF 45%). Regional wall motion abnormalities involved the inferolateral basal and mid-segments and lateral apical wall. T2-weighted imaging demonstrated focal subepicardial hyperintensity in the inferolateral wall consistent with active edema. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images revealed patchy subepicardial and mid-myocardial enhancement in matching territories, suggesting acute myocarditis. Additionally, there was focal wall thinning and festooning of the lateral wall (Figure 2).

Figure 2: CMR: LGE in inferolateral wall basal and mid-segments.

The patient improved clinically with NSAIDs, colchicine (0.5 mg/12 h), bisoprolol, and enalapril. She was discharged after ten days asymptomatic, with a diagnosis of acute myopericarditis with mildly reduced LVEF.

Should genetic testing be considered in this patient with chest pain, elevated biomarkers, and normal coronary arteries?

In recent years, genetic testing has become an essential tool in the evaluation of myocarditis, particularly when the clinical presentation suggests an inherited substrate. According to the 2025 ESC Myocarditis Guidelines, genetic testing should be performed when there is a family history of cardiomyopathy or sudden death, recurrent or complicated myocarditis, extensive LGE on CMR, or persistent LV systolic dysfunction.

Could this episode of myocarditis represent the first manifestation of an underlying cardiomyopathy?

Acute myocarditis can be the initial manifestation—or “hot phase”—of an underlying cardiomyopathy (CMP). Current evidence shows that pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in cardiomyopathy-associated genes are found in 4.2–22% of adults with myocarditis and up to 45% of pediatric cases. Desmosomal variants are most frequently seen in non-complicated cases, whereas sarcomeric and cytoskeletal gene variants (including DMD) predominate in more severe or arrhythmogenic presentations.

Regarding the relationship between myocarditis and DMD variants, there is limited evidence. Patients with mild DMD-associated cardiomyopathy present with chronic inflammation. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence supporting myocarditis as a trigger for the development of DMD-associated cardiomyopathy (e.g., Coxsackie B virus infection).

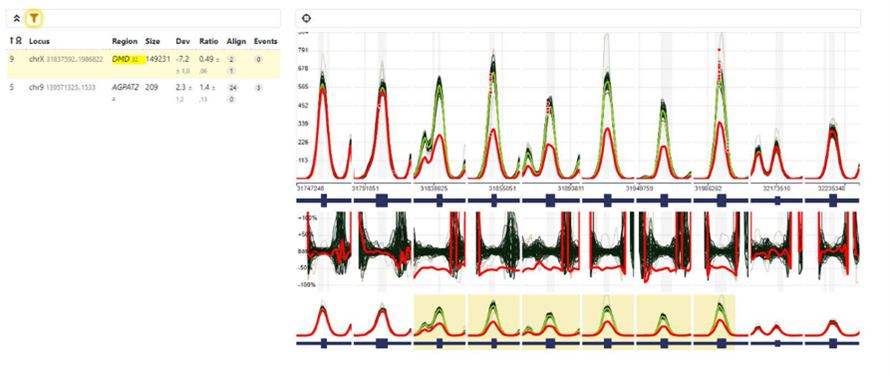

Given the CMR findings, a next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel for cardiomyopathy genes was performed. This identified a structural variant in the DMD gene: a deletion encompassing exons 45–50 of the NM_004006 isoform. Confirmation by MLPA revealed a heterozygous truncating variant in the DMD gene (c.6440dupG; p.Glu2147Leufs9*), classified as pathogenic under ACMG criteria. These findings established the final diagnosis of dystrophin-related cardiomyopathy presenting as acute myocarditis in a female carrier.

Figure 3. MLPA (Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification) analysis of the DMD gene showing a heterozygous deletion encompassing exons 45–50 of the NM_004006 isoform (X:31,837,592–31,986,822). The reduction of probe signal intensity (ratio ≈ 0.5) confirms carrier status for dystrophinopathy.

How can clinical management change when a genetic diagnosis is established instead of an apparently idiopathic myocarditis? What are the implications for follow-up and treatment?

Identifying a genetic cardiomyopathy redefines both the prognosis and follow-up strategy. In this patient, electromyography was normal, excluding overt skeletal involvement, but family screening was initiated.

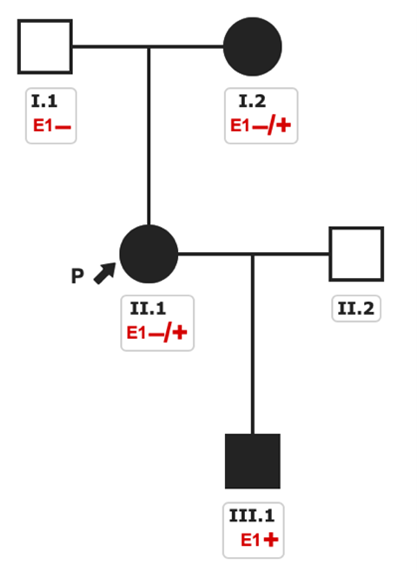

Cascade genetic testing revealed that her 2-year-old son, who was under neuropediatric evaluation due to muscle weakness and behavioral and neurodevelopmental abnormalities, was hemizygous for the same variant. He was diagnosed with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Her 79-year-old mother was found to be a heterozygous carrier, confirming X-linked inheritance. She had a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation without symptoms at the time of evaluation. Echocardiography and CMR revealed an LVEF of 49% and subepicardial LGE in the inferolateral wall, leading to a diagnosis of dystrophin-related cardiomyopathy as well.

Figure 4. Pedigree of the family with three affected family members diagnosed of distrophynopathy.

Why does the grandmother have mild cardiac disease while her 2-year-old grandson is severely affected?

Dystrophinopathies are X-linked inherited diseases. In males, complete absence of functional dystrophin (as in Duchenne disease) or partially functional dystrophin (as in Becker disease) determines disease severity. In heterozygous females, the phenotype is highly variable and often limited to the heart due to random X-chromosome inactivation (lyonization), leading to mosaic expression of the normal and mutant DMD alleles.

This case underscores the importance of considering genetic testing in patients with myocarditis. Although most cases follow a benign course without complications, clinicians should remain alert to features suggesting an underlying genetic substrate.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.