A 52-year-old Caucasian veteran triathlete is admitted to hospital with chest pain. He continues to compete on a regular basis and trains 6 hours per week. He doesn’t have any coronary risk factors and he is not on any regular medication. There is no family history of premature sudden cardiac death or cardiomyopathy. Clinical examination is unremarkable. He is kept under observation at the emergency department for twelve hours and repeat troponin tests are normal. An echocardiogram is performed and reported to be in keeping with athlete’s heart, thus he is reassured and discharged.

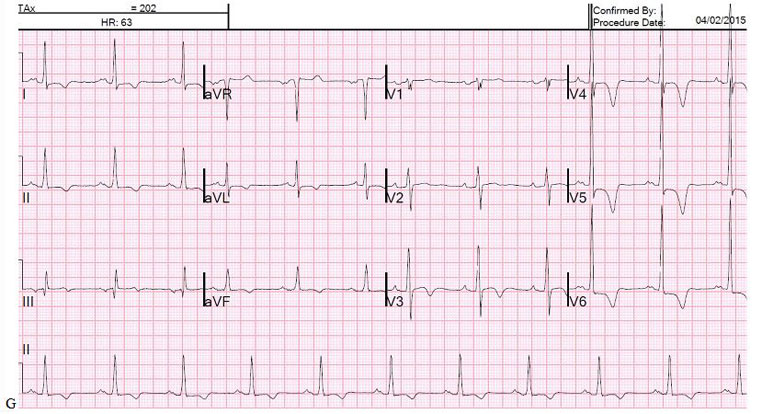

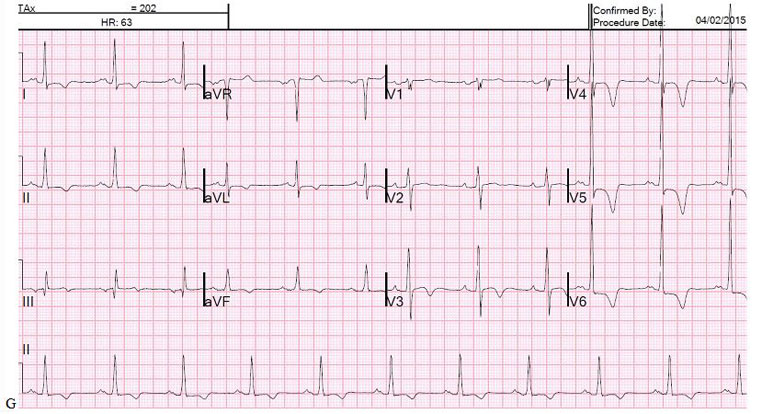

His 12-lead ECG on admission is presented below.

Test your knowledge

Interested in learning more? Access the ESC e-learning platform and discover the EAPC Sports Cardiology online courses.

Not yet an EAPC member?

JOIN NOW

Note: The views and opinions expressed on this page are those of the author and may not be accepted by others. While every attempt is made to keep the information up to date, there is always going to be a lag in updating information. The reader is encouraged to read this in conjunction with appropriate ESC Guidelines. The material on this page is for educational purposes and is not for use as a definitive management strategy in the care of patients. Quiz material in the site are only examples and do not guarantee outcomes from formal examinations.

References

- Papadakis M, Carrè F, Kervio G, et al. The prevalence, distribution, and clinical outcomes of electrocardiographic repolarization patterns in male athletes of African/Afro-Caribbean origin. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2304–13. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr140

- Papadakis M, Basavarajaiah S, Rawlins J, et al. Prevalence and significance of T-wave inversions in predominantly Caucasian adolescent athletes. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1728–35. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp164

- Rawlins J, Carre F, Kervio G, et al. Ethnic Differences in Physiological Cardiac Adaptation to Intense Physical Exercise in Highly Trained Female Athletes. Circulation 2010;121:1078–85. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.917211

- Pelliccia A, Di Paolo FM, Quattrini FM, et al. Outcomes in athletes with marked ECG repolarization abnormalities. N Engl J Med 2008;358:152–61. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060781

- Schnell F, Riding N, O'Hanlon R, et al. Recognition and significance of pathological T-wave inversions in athletes. Circulation 2015;131:165–73. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011038

- Kim JH, Noseworthy PA, McCarty D, et al. Significance of electrocardiographic right bundle branch block in trained athletes. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:1083–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.11.037

- Haghjoo M, Mohammadzadeh S, Taherpour M, et al. ST-segment depression as a risk factor in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Europace 2009;11:643–9. doi:10.1093/europace/eun393

- Sheikh N, Papadakis M, Ghani S, et al. Comparison of electrocardiographic criteria for the detection of cardiac abnormalities in elite black and white athletes. Circulation 2014;129:1637–49. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006179

- Gati S, Sheikh N, Ghani S, et al. Should axis deviation or atrial enlargement be categorised as abnormal in young athletes? The athlete's electrocardiogram: time for re-appraisal of markers of pathology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3641–8. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht390

- Corrado D, Pelliccia A, Heidbuchel H, et al. Recommendations for interpretation of 12-lead electrocardiogram in the athlete. Eur Heart J 2010;31:243–59. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp473

- Drezner JA, Ackerman MJ, Anderson J, et al. Electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes: the 'Seattle criteria'. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:122–4. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-092067

- Caselli S, Maron MS, Urbano-Moral JA, et al. Differentiating left ventricular hypertrophy in athletes from that in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:1383–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.070

- Sheikh N, Papadakis M, Schnell F, et al. Clinical Profile of Athletes With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 2015;8:e003454. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.003454

- Sheikh N, Papadakis M, Schnell F, et al. The clinical profile of athletes with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the ‘grey zone’ revisited. Circulation Cardiovascular Imaging 2015.

- Gati S, Chandra N, Bennett RL, et al. Increased left ventricular trabeculation in highly trained athletes: do we need more stringent criteria for the diagnosis of left ventricular non-compaction in athletes? Heart Published Online First: 7 February 2013. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303418

- Schulz-Menger J, Abdel-Aty H, Busjahn A, et al. Left ventricular outflow tract planimetry by cardiovascular magnetic resonance differentiates obstructive from non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2006;8:741–6. doi:10.1080/10976640600737383

- Bogaert J, Olivotto I. MR Imaging in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: From Magnet to Bedside. Radiology 2014;273:329–48. doi:10.1148/radiol.14131626

- Maron MS, Olivotto I, Harrigan C, et al. Mitral valve abnormalities identified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance represent a primary phenotypic expression of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2011;124:40–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985812

- Maron BJ, Harding AM, Spirito P, et al. Systolic anterior motion of the posterior mitral leaflet: a previously unrecognized cause of dynamic subaortic obstruction in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1983;68:282–93.

- Maron MS, Rowin EJ, Lin D, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of myocardial crypts in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 2012;5:441–7. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.972760

- Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2733–79. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284

- Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Prognostic value of quantitative contrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2014;130:484–95. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007094

- Briasoulis A, Mallikethi-Reddy S, Palla M, et al. Myocardial fibrosis on cardiac magnetic resonance and cardiac outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a meta-analysis. Heart 2015;101:1406–11. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307682

Notes to editor

Dr Gherardo Finocchiaro, Clinical research fellow, St George’s university of London

Dr Michael Papadakis, Lecturer in cardiology, St George’s university of London

Prof Sanjay Sharma, Professor of clinical cardiology, St George’s university of London

|

|

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.