Idiopathic ventricular tachycardia (IVT) is a term that has been used for ventricular tachycardia (VT) in the absence of clinically apparent structural heart disease (1). It accounts for approximately 10% of all VTs evaluated in specialised arrhythmia services. Several types have been reported according to their clinical presentation, ventricular origin, response to drugs, electrocardiographic pattern, among other parameters.

Idiopathic fascicular left ventricular tachycardia (IFLVT) is the most common IVT of the left ventricle and represents the 10-15% of all IVT. Other less common variants of left IVT are left ventricular outflow tract ventricular tachycardia and, exceptionally, the catecholaminergic monomorphic VT or sensitive to propranolol VT (2). Zipes et al first described IFLVT in 1979 (3). They reported three cases of patients without structural heart disease who developed ventricular tachycardia with right bundle branch block (RBBB) morphology and left axis after atrial pacing. They also highlighted the relatively narrow QRS of these VT and related it to the proximity of the origin of the tachycardia to posterior fascicle. Two years later, Belhassen et al (4) described another of its main features: its sensitivity to verapamil. They observed that its administration in these patients not only interrupted the tachycardia but also reduced the number of recurrences. Subsequently, in larger series, VTs with similar behaviour were described in other locations: the anterosuperior region of the ventricular septum (5) and the left superior septum (6).

1 - Mechanism

Although triggered activity was at first postulated as a potential mechanism (3), later studies showed that IFLVT behaves electrophysiologically as a reentrant tachycardia (7-12).

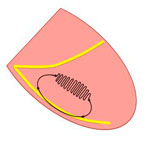

In the most common form, - posterior IFLVT, (P-IFLVT), the reentrant circuit extends from the basal to the mid-apical region of the interventricular septum. The entrance to the circuit is located in the basal interventricular septum. From there, the wave front spreads in an apical direction along the so-called antegrade arm. It has been suggested that it could be formed by abnormal Purkinje fibbers since it shows decremental properties, and sensitivity to verapamil and constitutes the slow zone of the circuit. At the distal interventricular septum, the circuit changes its meaning. On the one hand, the activation front continues to advance distally and on the other hand, it returns along the posterior fascicle, which acts as the retrograde arm of the circuit (figure 1). Less frequently, the circuit can use as retrograde arm the anterior fascicle anterior IFLVT, (A-IFLVT) as retrograde arm.

Regarding the anatomical substrate, it is not clear if whether the circuit contains only fascicular tissue or if there is myocardial involvement as well. Though it is generally accepted that the posterior fascicle constitutes the retrograde arm of the circuit, there are still concerns about the histology of the antegrade arm. In the late 80's, it was suggested that it could be related to the existence of a false tendon extending from the muscular left ventricular posterior wall to the basal septum (13). This hypothesis was based on the fact that these tendons were very common in patients with ILFVT and they showed histologically abundant abnormal Purkinje fibbers inside. In addition, it was supported by some reported cases of cure after resection of the tendon. The later findings of a high prevalence of this muscular band in the normal population led to the rejection of the fibromuscular band as an specific substrate of this arrhythmia, though a role in its genesis can be ruled out (14). Other hypotheses have suggested that the circuit could be formed by a longitudinal dissociation of the affected fascicle or even ventricular myocardium.

2 - Clinical presentation

ILFVT typically presents in young adults (15 to 40 years) and mainly affects males (60-80%)(15-17). The most frequent clinical presentation is paroxysmal episodes of palpitations, dizziness and, less frequently, syncope. Tachycardiomyopathy has been described in the 6% of cases as a result of persistent tachycardia and it is usually reversible after successful ablation (16). Although most episodes occur at rest, exercise, emotional stress and catecholamine infusion can act as triggers.

3 - Electrocardiographical features

The baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) is normal in most patients though it may present T-wave inversion immediately after tachycardia (cardiac memory).

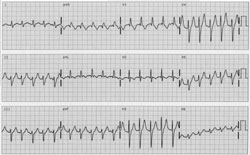

Unlike patients with structural heart disease, IFLVT usually shows a QRS complex duration inferior to 140-150 ms and fast initial forces (RS interval of 60-80 ms). Both features can lead to misdiagnosis of aberrant supraventricular tachycardia. The electrocardiographical pattern varies depending on the site of origin of the tachycardia:

- Posterior fascicular ventricular tachycardia (P-IFLVT). It accounts for the 90-95% of cases. P-IFLVT is electrocardiographically characterised by right bundle branch block (RBBB) morphology and left axis suggesting that the exit of the circuit is located in the inferoposterior septum (figure 2).

- Anterior fascicular ventricular tachycardia (A-IFLVT). It is the second variant in terms of frequency. Its ECG pattern typically shows RBBB morphology and right axis. The earliest activation has been described in the anterolateral wall of the left ventricle (18).

- Upper septal fascicular ventricular tachycardia. This presentation is exceptional. As a general rule, it presents RBBB but a few cases with morphology of left bundle branch block have also been described. A narrow QRS and normal frontal axis have been reported too.

4 - Differential Diagnosis

As in other idiopathic ventricular tachycardia, IFLVT diagnosis requires exclusion of structural heart disease. It is therefore recommended to perform echocardiography and coronary angiography or computed tomography, if deemed necessary depending on the cardiovascular risk profile of the patient.

Quite often, the IFLVT can be confused with a paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia conducted with aberrancy because of its relatively narrow QRS, response to verapamil and presentation in young patients without structural heart disease. The presence of ventriculoatrial dissociation in the electrocardiogram or during the electrophysiological study may clarify the diagnosis.

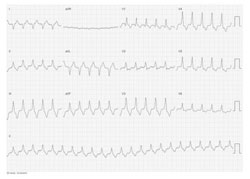

It must also be distinguished from other forms of ventricular tachycardia with narrow QRS. This is the case of ventricular tachycardia related to intramyocardial reentry close to the conduction system in which the QRS may be narrow due to an early invasion of the His-Purkinje system. As well, verapamilo sensitive ventricular tachycardia originating from the mitral annulus should be considered. They can present morphology of RBBB, right axis and a relatively narrow QRS, but its clinical and electrophysiological behaviour is usually different (figure 3). An exceptional entity to consider is the interfascicular ventricular tachycardia. In this case, the tachycardia circuit is established between the two fascicles, either one or another sense. The QRS morphology is similar in sinus rhythm and tachycardia, right bundle branch block and anterior or posterior hemiblock. The ablation of one of the fascicles resolved successfully the tachycardia (19).

5 - Treatment

- Acute Management

As in other cases of wide QRS tachycardia, we should evaluate the hemodynamic status of the patient. Electrical cardioversion is emergent in case of tachycardia intolerance. In stable patients, as its name suggests, first line treatment is verapamil. The intravenous administration of 10 mg (given for over 1 minute) can interrupt this tachycardia due to its calcium-dependence. The risk of hemodynamic collapse in cases of wrong diagnosis makes it advisable to only administrate verapamil in stable patients with an established diagnosis. However, unlike other idiopathic ventricular tachycardia, IFLVT usually does not respond to vagal manoeuvres, adenosine or beta-blockers. This has been attributed to the fact that IFLVT depends on the slow entry of calcium in partially depolarised Purkinje fibbers and not the cAMP-mediated triggered activity occurring in the adenosine-sensitive VT (20). A response to adenosine has been observed only in patients in whom the tachycardia is triggered by catecholamines. In these circumstances, there is an important component of cAMP production dependent on intracellular calcium influx that gives them some sensitivity to adenosine (21). The IA and IC drug classes may also be effective.

- Long-term management

With its excellent prognosis, treatment depends on the severity and frequency of symptoms. Verapamil may be helpful in patients with mild symptoms. When symptoms are severe and pharmacologic treatment is not effective or is poorly tolerated, catheter ablation is recommended (1,22). Ablation success rates as reported in various series vary between 85 and 95%, and are generally higher in those patients with posterior IFLVT. Recurrence rates are also lower in these patients as well (5% vs. 12.5%). Although complications are rare, the most common one is the development of left bundle branch or atrioventricular block, transient in all reported reported cases. It is also possible to damage the aortic valve if retrograde aortic approach is performed or to damage the mitral valve in cases of transeptal puncture.

Figure 1. Reentrant circuit in posterior idiopathic fascicular left ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 2. Electrocardiogram of a patient with posterior idiopathic fascicular left ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 3. Electrocardiogram of a patient with adenosine sensitive ventricular tachycardia originating from the mitral annulus.

Conclusion:

Idiopathic fascicular left ventricular tachycardia (IFLVT) is the most common idiopathic ventricular tachycardia (IVT) of the left ventricle. Electrophysiologically, IFLVT behaves as a reentrant tachycardia. In the most common form - posterior IFLVT-, the reentrant circuit extends from the basal to the mid-apical region of the interventricular septum. It is generally accepted that the posterior fascicle constitutes the retrograde arm of the circuit, however there are still concerns regarding the histology of the antegrade arm. ILFVT typically presents in young adults and mainly affects males. IFLVT usually shows narrow QRS and fast initial forces. Posterior IFLVT is electrocardiographically characterised by right bundle branch block (RBBB) morphology and left axis. Its diagnosis requires exclusion of structural heart disease. During the episode, in stable patients, first line treatment is verapamil. Because of its excellent prognosis, long-term management will depend on the severity and frequency of symptoms. Catheter ablation is recommended when symptoms are severe and pharmacologic treatment is not effective or is poorly tolerated.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.