Background

Professional and amateur athletic training can cause pressure and volume overload of the cardiovascular system which in this situation may far exceed its ordinary exercise capacity. Extreme physical effort may be a trigger for serious and often fatal cardiovascular events in athletes with previously undetected underlying heart or vascular disease. Thus, every professional or amateur athlete with a recognised or suspected cardiovascular disease must undergo a specialised diagnostic and qualification process before a training program is prescribed or continued.

Causes and consequences

Regular and very intensive athletic training is a tremendous burden for the cardiovascular system which often induces adaptational changes in its structure and function as observed in echocardiography and electrocardiography (ECG). However, these physiologic changes referred to as the “athlete’s heart” may coincide with structural cardiac disease and also be a cofactor for dramatic deterioration of clinical status in a certain group of athletes. According to Corrado et al. competitive sport activity enhances by 2.5 the risk of sudden death in adolescents and young athletes (1).

The most important aftermath of cardiovascular diseases in athletes is exercise-induced ventricular arrhythmia - ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF) (92-98%). It is well explained by the pathophysiology of arrhythmias.

Ventricular arrhythmias depend on three interrelated factors:

- Arrhythmogenic substrates which are congenital or acquired cardiovascular diseases

- A trigger – in the case of endurance athletes, it is extreme physical exercise or sport event-related chest trauma

- Pathophysiologic conditions such as autonomic nervous system dysregulation with excessive adrenergic stimulation, dehydration, heat stress and water-electrolyte imbalance which are often observed during strenuous physical effort.

According to the various accessible medical records, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), congenital heart defects, premature coronary artery disease are the most frequent causes of cardiovascular events in athletes (2,3). Hypetrophic cardiomyopathy has been reported to be one of the leading causes of sport-related heart arrest and death in athletes and non-athletes (2). However, other cardiovascular abnormalities such as anomalies of coronary vessels, arrhythmogenic dysplasia of right ventricle (ADRV), mitral valve prolapse, myocarditis, coronary vessel bridge, Marfan Syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, pulmonary thrombo-embolism and channelopathies also significantly contribute to cardiovascular risk in athletes.

Role of the cardiologist

The clinical cardiologist and sports cardiologist have three major roles in the screening process of professional or amateur athletes and athletic training candidates with cardiovascular diseases:

- Identification of the risk of cardiovascular events by means of clinical examination (symptoms, physical examination, family history of cardiovascular diseases, biochemical markers of cardiovascular disease risk, history of alcohol and drug abuse, nicotine addiction, medication, illegal doping) and various diagnostic modalities (electrocardiography, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, echocardiography or magnetic resonance imaging)

- Prescription of an appropriate exercise program (static, dynamic with low, moderate or high intensity)

- Regular medical check-up.

I - Identification of cardiovascular risk before exercise prescription in athletes

1 - Medical history

The majority of sport–related cardiovascular events are induced by genetically determined diseases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, hence the importance of family history in identifying affected athletes. The family history of cardiovascular diseases is considered positive in athletes when close relatives had experienced a premature heart attack or sudden death (below 55 years of age in males and 65 years in females), or suffered from cardiomyopathy, Marfan syndrome, long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, severe arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, or other disabling cardiovascular diseases. The positive familial history can be especially helpful in athletes without any clinical symptoms of disease and should encourage a doctor to perform further necessary examinations (resting ECG, echocardiography, ECG Holter monitoring or eventually genetic tests). A certain number of athletes with rare and genetically conditioned cardiomyopathies (e.g. arrhythmogenic dysplasia of right ventricle) may not have any preceding symptoms of disease (4). Personal history must be considered positive in the case of exertional chest pain or discomfort, syncope or near-syncope, irregular heartbeat or palpitations, and in the presence of shortness of breath, or fatigue unproportionate to the degree of physical effort (3). The seemingly noncardiac chest pain not related to physical exercise may also be caused by congenital or acquired cardiovascular disease (e.g. bicuspid aortic valve, dilatation or aneurysm of ascending aorta) and should be investigated before intensive training is started.

2 - Physical examination and diagnostic modalities

Positive physical findings related to cardiovascular diseases in athletes include: musculoskeletal and ocular features suggestive of Marfan syndrome, diminished and delayed femoral artery pulses, mid- or end-systolic clicks, a second heart sound single or widely split and fixed with respiration, marked heart murmurs (any diastolic and systolic murmur grade>2/6), irregular heart rhythm and brachial blood pressure above 140/90 mmHg in resting conditions (on more than 1 reading) and inter-arm systolic blood pressure difference above 10mmHg (5). However, lack of significant familial history of cardiovascular diseases and normal physical examination do not preclude presence of serious cardiac anomaly. On the other hand, presence of abnormalities in physical examination (murmurs, heart rhythm irregularities) need not be a symptom of serious heart disease. Subsequently, taking history and physical examination should be supplemented by electrocardiographic record at rest, exercise test (preferably cardiopulmonary exercise testing - CPET) and, if necessary, other diagnostic procedures (chest X-ray, holter ECG monitoring, echocardiography, computed tomography, nuclear magnetic imaging) before exercise is prescribed. Steriotis et al. have recently demonstrated that resting ECG is normal in a majority of examined athletes. However, ECG exercise test has induced ventricular arrhythmia that was deemed hazardous in 30% of these athletes (6). Hence, CPET may help to exclude exercise-induced arrhythmia or myocardial ischaemia, assess blood pressure response, exercise tolerance, achieved maximal heart rate (MHR), aerobic and ventilatory capacity (VO2max,VO2 at anaerobic threshold, minute ventilation) for selection of best training program or sport discipline regarding its type (static, dynamic) and intensity (low, moderate, high) (7). CPET can also be helpful in discriminating between pathologic LV hypertrophy (HCM) and physiologic exercise-induced LV hypertrophy (VO2max >50ml/kg/min is more consistent with athlete’s heart).

Resting ECG record can be especially valuable in diagnosis of potentially lethal pathologies in athletes such as long and short QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, ARVD and WPW. Unfortunately, resting ECG and ECG stress tests or even echocardiography can be nonproductive in congenital anomaly of coronary vessels. If this disease is suspected in young athletes (exercise-induced syncope of unknown origin, ventricular arrhythmia) computed tomography of coronary vessels can be indicated. Furthermore, electrocardiography can be normal in approximately 5% of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Rowin et al. have recently demonstrated that 10 % of examined young patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy presented normal or nonpathologic ECG (8). Moreover, trained athletes without evident cardiovascular disease may occasionally show ECG abnormalities similar to those found in patients with HCM (9). Hence, echocardiographic screening should be considered as a diagnostic option especially in athletes with familial history of HCM, ARVD or sudden cardiac death and obviously in athletes with abnormal resting ECG and upsetting symptoms before exercise is prescribed. Although normal ECG has very strong negative predictive power in pre-participation screening of young athletes for HCM, the disease may develop in midlife and beyond in some individuals and can be precipitated by intensive training. Besides, ECG pathologic changes may precede the LV hypertrophy and should raise the suspicion of the disease in athletes with a family history of HCM. Then, regular ECG and echocardiography screening should be recommended especially in high risk groups of HCM athletes during a course of regular intensive training and after termination of competitive exercise.

In all, the recommended steps for comprehensive evaluation of athletes with congenital or acquired cardiovascular disease before exercise are:

- History and physical examination

- Assessment of ventricular function, aorta and pulmonary artery pressure by echocardiography or other imaging techniques

- Assessment of arrhythmias/ischaemia and other electrical abnormalities by ECG

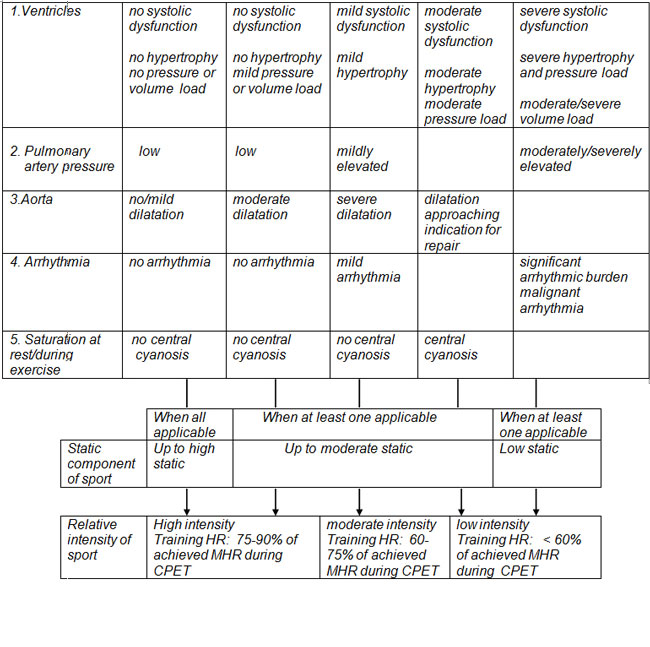

- Recommendation on intensity and type of exercise and risk assessment by CPET (10) (Table 1Table 1: Recommendation on intensity and type of exercise and risk assessment by CPET.

II - Athletes with cardiovascular diseases

1 - Congenital and acquired heart defects

In patients with congenital heart defects (CHD), dynamic exercise is more advisable than static exercise. However, competitive sports are contraindicated in patients with some defects, due to high risk of malicious arrhythmias, such as Eisenmenger Syndrome, coronary artery anomalies, Ebstein anomaly, transposition of great vessels corrected by Mustrad, Senning or Rastelli procedure. As for the other congenital or acquired defects (presented below), exercise prescription depends on the severity of the defect, and the hemodynamics and clinical symptoms of the disease.

Atrial septal defect (closed or small unoperated) and patent foramen ovale (PFO)

- Below a 6 mm defect, or 6 months post-closure, with normal pulmonary artery pressure, no significant arrhythmia or ventricular dysfunction: all sports are recommended.

- In patients with PFO, percutaneous closure may be considered before regular scubadiving because of high risk of decompression illness and systemic embolism.

Ventricular septal defect (closed or small unoperated)

- Restrictive defect (left-to-right gradient above 64 mmHg) or 6 months post-closure, no pulmonary hypertension: all sports are recommended.

Pulmonary stenosis

- Mild native or 6 months after post-interventional/post-surgical; peak transvalvular gradient below 30 mmHg, normal RV in echocardiography, normal ECG or only mild RV hypertrophy, no significant arrhythmias: all sports are recommended.

- Moderate native or 6 months post-interventional/post-surgical; peak transvalvular gradient between 30 and 50 mmHg, normal RV in echocardiography, normal ECG or only mild RV hypertrophy: low and moderate dynamic and low static sport recommended (e.g. golf, cricket, riflery, fencing, volleyball, sprint running).

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP)

Athletes with recognised MVP are restricted from competitive sports in case of:

- Syncope of unknown aetiology

- Family history of sudden cardiac death in person with MVP

- Presence of paroxysmal supraventricular and complex ventricular arrhythmias that are induced by exercise or deteriorate while exercise

- Moderate or severe mitral regurgitation

- Marfan syndrome

- Long QT syndrome

Athletes with MVP and at least one of the aforementioned restrictions should not participate in competitive sports.

Mitral valve regurgitation

Mild-to-moderate, normal LV size/function, stable sinus rhythm, normal exercise testing: all sports are recommended.

Aortic valve stenosis

- Mild aortic stenosis, normal LV size and function at rest and under stress, no symptoms, no significant arrhythmia: low-moderate dynamic (e.g. bowling, golf, fencing, sprint running, figure skating) and low-moderate static sports (e.g. auto racing, diving, sailing, karate/judo).

- Moderate aortic stenosis, normal LV size and function at rest and under stress, no symptoms, no significant arrhythmia: low dynamic and low static sports (e.g. bowling, golf, riflery).

- Moderate aortic stenosis with LV dysfunction and symptoms and severe aortic stenosis: no competitive sports.

Aortic regurgitation

- Mild-to-moderate regurgitation, normal LV size and function, normal exercise testing, no significant arrhythmia: all sports are recommended.

- Mild-to-moderate regurgitation, proof of progressive LV dilatation: only low dynamic and low static sports (e.g. bowling, cricket, golf, riflery).

- Mild-to-moderate regurgitation, significant ventricular arrhythmia at rest or under stress, dilatation of the ascending aorta: no competitive sports.

- Severe aortic regurgitation: no competitive sports.

Tricuspid regurgitation

- Mild-to-moderate regurgitation: only low-moderate dynamic and low-moderate static sports recommended (e.g. bowling, cricket, fencing, skate dancing, golf, sprint running, volleyball).

- Any degree with right atrial pressure above 20mmHg: no competitive sports.

2 - Cardiomyopathies

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

Athletes with definite diagnosis of HCM should not participate in competitive sports at all. Athletes with ECG abnormalities (such as markedly increased QRS voltage, diffuse T-wave inversion, deep Q-waves in precordial leads) suggestive of HCM should undergo detailed clinical examination (personal history, echocardiography, 24 h Holter monitoring). When sudden cardiac death (SCD) or HCM in the family are excluded, and in the absence of symptoms, arrhythmias and significant LV hypertrophy, and with a normal LV diastolic filling/relaxation on echocardiography and blood pressure response to exercise, there is no reason for restricting athletes from competitive low dynamic and low static sports (e.g. bowling, cricket, riflery, golf). However, periodical clinical and diagnostic follow-up is recommended.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

Athletes with definite diagnosis of DCM should not participate in competitive sports. However, athletes with DCM but low risk profile (no sudden death in the relatives, no symptoms, mildly depressed LV ejection fraction - 40%, normal blood pressure response to exercise, no complex ventricular arrhythmias in ECG and holter monitoring) may perform low-moderate dynamic and low static sports (e.g. fencing, table tennis, golf, cricket).

Arrhythmogenic Dysplasia of Right Ventricle (ADRV)

Athletes with a definite diagnosis of ADRV are absolutely restricted from participating in sport activities even if they have very good exercise tolerance because of a very high risk of malicious ventricular tachyarrhythmia. ADRV is one of the most frequent causes of SCD in young athletes.

3 - Ischaemic heart disease (IHD)

4 - Systemic hypertension

- Athletes with systemic hypertension can participate in sport activities provided risk stratification and appropriate management of hypertension according to general rules are observed.

- Athletes with well controlled blood pressure and no other cardiovascular risk factors can participate in all sports.

- Athletes with well controlled blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors should avoid high static and high dynamic sports (e.g. weight lifting, marathon running, boxing, swimming, tennis, cycling).

5 - Arrhythmias

- Marked sinus bradycardia (below 40 b.p.m.) and/or sinus pauses (3 s) with symptoms, no cardiac disease: temporary interruption of sport; after > 3 months from resolution of symptoms all sports are recommended.

- First and second degree AV block (type 1) and, if no symptoms, no cardiac disease, with resolution during exercise: all sports are recommended.

- Second degree AV block (type 2) and, if no symptoms, no cardiac disease, no ventricular arrhythmia during exercise, resting heart rate above 40 b.p.m.: low-moderate dynamic or static sports recommended (e.g. bowling, fencing, volleyball, sprint running).

- Supraventricular premature beats, no symptoms, no cardiac disease: all sports are recommended.

- Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (AVNRT or AVRT over a concealed accessory pathway): ablation is recommended before exercise prescription

- Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia: all sports are recommended in the absence of

- Cardiac disease or arrhythmogenic condition

- Symptoms and family history of SCD

- Exercise-induced nsVT

- Multiple episodes of nsVT with short RR interval

- Athletes with symptomatic and asymptomatic pre-excitation should be advised to undergo electrophysiology study and preferably catheter ablation (if feasible) because of an increased risk of SCD before exercise prescription

- Atrial flutter: ablation is mandatory before exercise prescription

- Long QT and Brugada syndrome: no competitive sports

Conclusions

The type and intensity of exercise can be prescribed in athletes with cardiovascular problems after risk stratification based on detailed physical examination, family history, ECG, cardiopulmonary exercise testing and imaging techniques.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.

Our mission: To reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease.